Strange crater suggests ancient Mars may have been frigid with occasional snowmelt

One crater on Mars shows signs of an ancient glacier that melted from the top down.

One strange Mars crater could offer a new possibility about what ancient Mars was like.

Mars' ancient history interests scientists because if the arid planet was once warm and wet, it may have been habitable to life. One new study about an unnamed Martian crater suggests a new possibility about Mars' past.

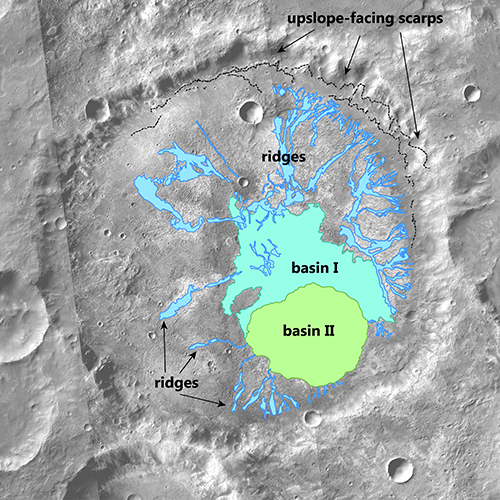

A spacecraft orbiting Mars captured incredible images of the calloused floor of a crater located in the southern highlands of Mars. This 33.5 mile-wide (54 km) crater dates back 4.1 to 3.7 billion years ago to the Noachian period, when Mars may have been much warmer and may have been home to bodies of water and ice, ingredients that are key to life as we know it on Earth.

In a new study, scientists at Brown University took a look at the peculiar ridges and geological features of this crater that were visible in imagery from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Related: The 7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars

According to their paper, published March 12 in the Planetary Science Journal, the team noticed that these formations are different from those found in other craters. While all the craters in the scope of their comparative analysis had signs that water once flowed within them, the unnamed crater showed no signs that water breached the wall of the crater to get inside. There was also no evidence that groundwater was the source of the ridges inside the crater, they found.

This puzzled the team, and they arrived at a fascinating explanation: the source of the liquid water was a glacier that melted from the top down.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There's little doubt that the Martian climate was once warmer and wetter than the frozen desert the planet is today. What's less clear, however, is whether Mars had an Earthlike climate with continually flowing water for millennia, or whether it was mostly cold and icy with fleeting periods of warmth and melting.

This finding has implications beyond just this one individual crater. For this glacier to exist in the first place, Mars may not have been continuously balmy during the Noachian period. It may have, instead, been a frigid place populated with many other glaciers, and the liquid water that leaves its fingerprints in many places across the Red Planet might be from snowmelt that formed after brief moments of planetary heating.

"This [explanation] would favor a colder, potentially subfreezing Noachian climate with only transient warming. Some global climate modeling studies support ambient Noachian temperatures well below freezing... with cold-based glaciation occurring in the southern highlands ... Thus, the nature of the ambient Noachian martian climate is currently debated," the study's authors wrote in their paper.

"The cold and icy scenario has been largely theoretical — something that arises from climate models," lead author and Brown Ph.D. student Ben Boatwright stated in a press release about the study. "But the evidence for glaciation we see here helps to bridge the gap between theory and observation. I think that's really the big takeaway here."

Missions like NASA's Perseverance rover may find clues that continue the discourse about Mars' ancient past. The type of lake described in this study, however, is quite different from Jezero crater, where Perseverance is currently exploring.

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.