Feeding supermassive black holes are more common than thought across the universe

"If our eyes were able to detect X-rays, the sky would be full of dots. And every single one of those dots would be an accreting supermassive black hole."

The universe could be packed with many more monstrous black holes ravenously feeding on their surrounding material than previously suspected.

That's the conclusion of a team of scientists, who theorize that astronomers could be missing between 30% to 50% of feeding supermassive black holes, cosmic titans that have masses equivalent to millions or even billions of suns.

Don't worry; these cosmic monsters aren't hiding under the bed (we guarantee you'd notice if they were). Instead, they seem to be lurking behind the vast veils of galactic gas and dust that help feed them.

"The relative size scales of a supermassive black hole to its host galaxy is like comparing a pea to the Earth," study team leader Peter Boorman, a researcher at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said at the 245th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in National Harbor, Maryland on Monday (Jan. 13).

"But despite that extreme size difference, an accreting supermassive black hole has the potential to unleash havoc or have a positive influence on its host galaxy," Boorman added.

Related: Black holes: Everything you need to know

That's because when black holes "overfeed," they can blast jets of material from their immediate surroundings at around 33% the speed of light. These astrophysical jets can push away the gas and dust needed for their home galaxies to form stars. Thus, an erupting black hole can slow or even kill star formation in its surrounding galaxy.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This has a dramatic implication for our perception of galaxy evolution," Boorman continued. "There's one component of this picture that is often overlooked: obscuration."

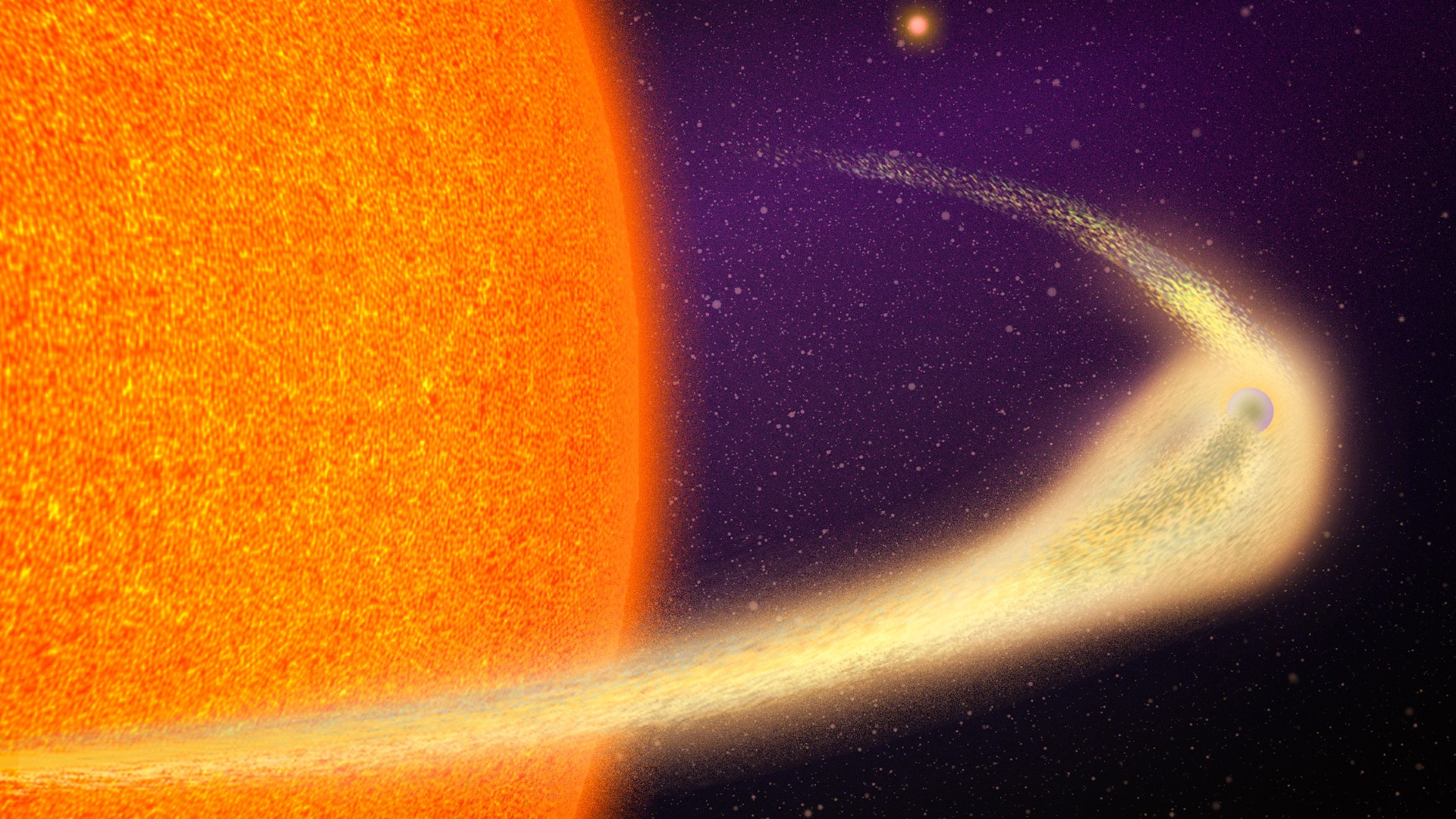

Obscuration is the hiding of feeding or "accreting" supermassive black holes in otherwise bright regions called active galactic nuclei (AGN) by the very platters of gas and dust they feed on.

Black holes hide behind donuts

The Caltech researcher, formally of the University of Southhampton in England, explained that feeding and growing supermassive black holes couldn't exist without some kind of reservoir of material around them — a "cosmic buffet" from which they feed.

"It's believed that this material can form the approximate geometrical shape of a donut," Boorman said. "Depending on the orientation of that material towards our line of sight, we either see down to the center of the accreting material, which is very bright, or we see heavy obscuration."

Previously, research has indicated that this obscuration could be hiding as many as 15% of feeding supermassive black holes from our view.

Boorman and colleagues tested this idea with infrared data from NASA's Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) spacecraft, as part of a project called NuLANDS (NuSTAR Local AGN N H Distribution Survey).

The result was the visualization of infrared light coming from clouds surrounding supermassive black holes. This enabled the team to create the first highly refined census of black holes growing by consuming the matter around them.

"Though black holes are dark, surrounding gas heats up and glows intensely, making them some of the brightest objects in the universe," team member and Southhampton University researcher Poshak Gandhi said in a statement. "Even when hidden, the surrounding dust absorbs and re-emits this light as infrared radiation, revealing their [black hole's] presence.

"We’ve found that many more are lurking in plain sight — hiding behind dust and gas, rendering them invisible to normal telescopes."

Hunting out hidden feeding black holes could help explain how they grow to such tremendous sizes. It could also help paint a better picture of how galaxies evolve.

"If we didn’t have black holes, galaxies could be much larger," Gandhi said. "If we didn’t have a supermassive black hole in our Milky Way galaxy, there might be many more stars in the sky.

"That’s just one example of how black holes can influence a galaxy’s evolution."

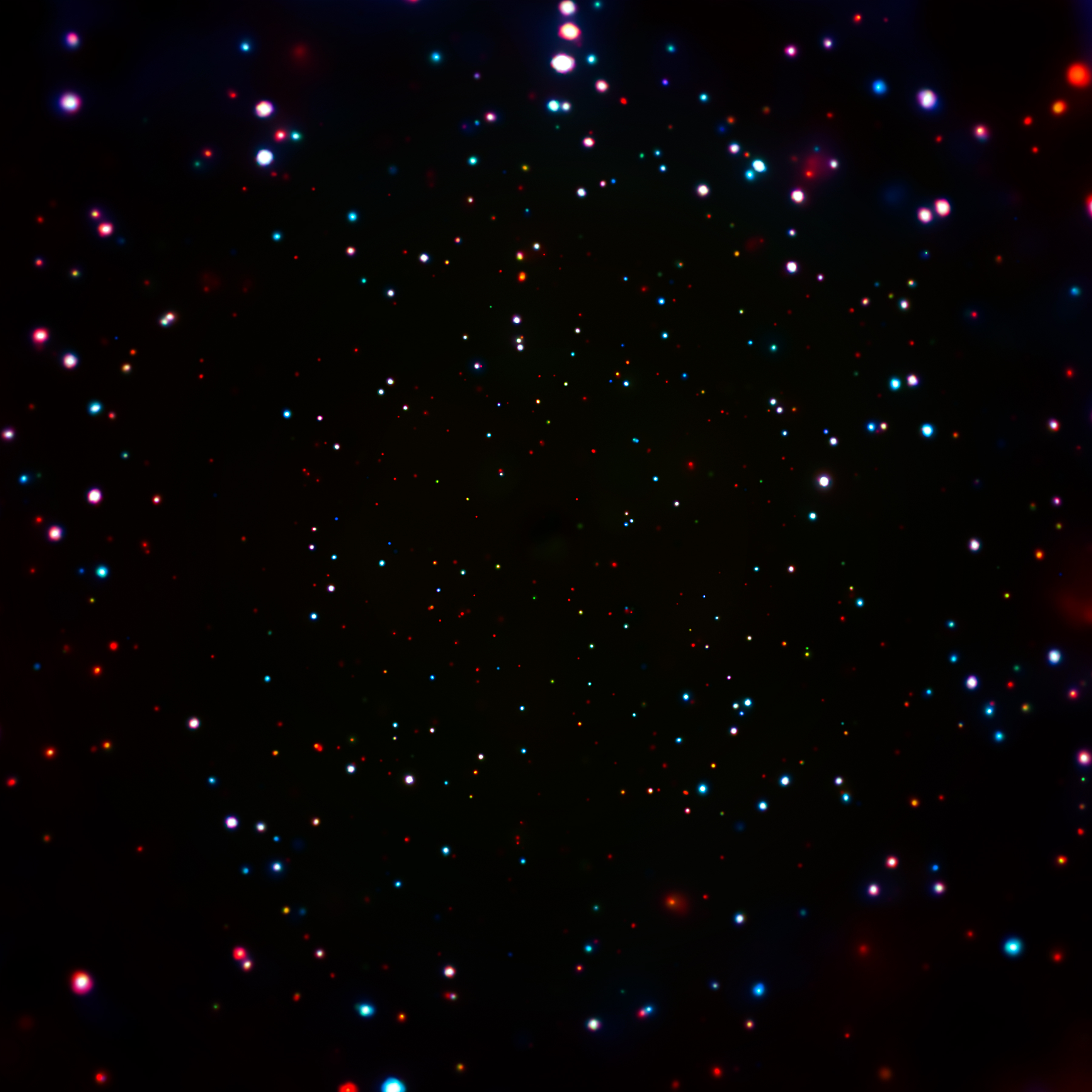

Boorman explained how different our view of the universe would be if we could see its content of feeding supermassive black holes.

"If our eyes were able to detect X-rays, the sky would be full of dots," Boorman said. "And every single one of those dots would be an accreting supermassive black hole."

The team's research was published on Dec. 30 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.