Able and Baker: The First Primates to Survive Spaceflight in Photos

The mismatched monkey duo made space history.

In 1959, the U.S. needed a Cold War win and the country was eyeing spaceflight. And so a pair of mismatched monkeys found themselves bundled up and placed in a Jupiter missile. Dubbed Able and Baker, they became the first primates to survive spaceflight during a suborbital predawn flight on May 28, 1959.

Their survival made them instant celebrities, although spaceflight was not the most dramatic part of their stories. To announce their successful flight, NASA unveiled Able and Baker to journalists in the same room where just a month prior they had introduced the Mercury 7 as the country's first human astronaut candidates.

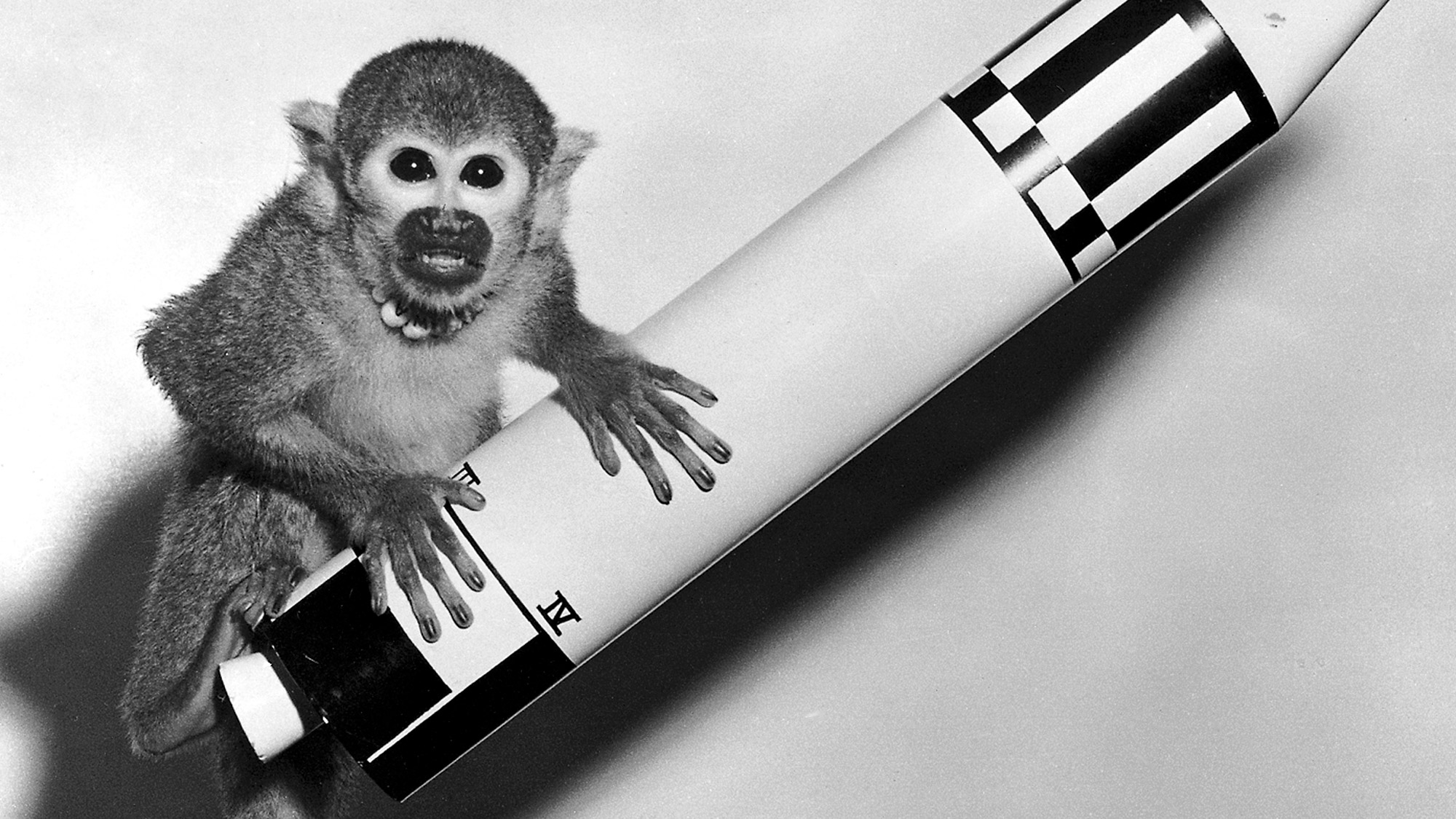

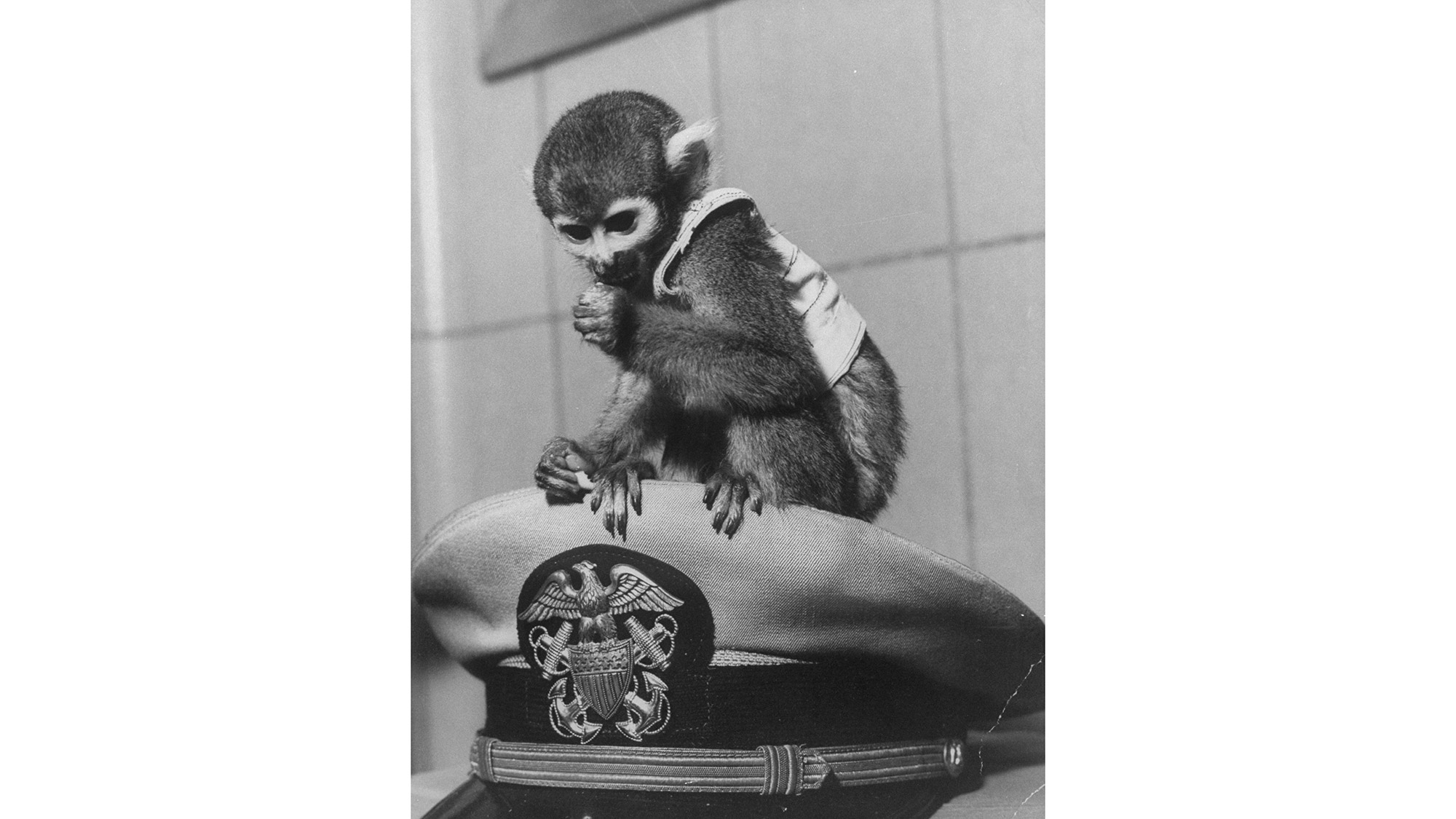

Here, Baker, who was a squirrel monkey, poses with a model of the Jupiter rocket she and Able flew.

Full story: Two Female Monkeys Went to Space 60 Years Ago. One Became the Poster Child for Astronaut Masculinity

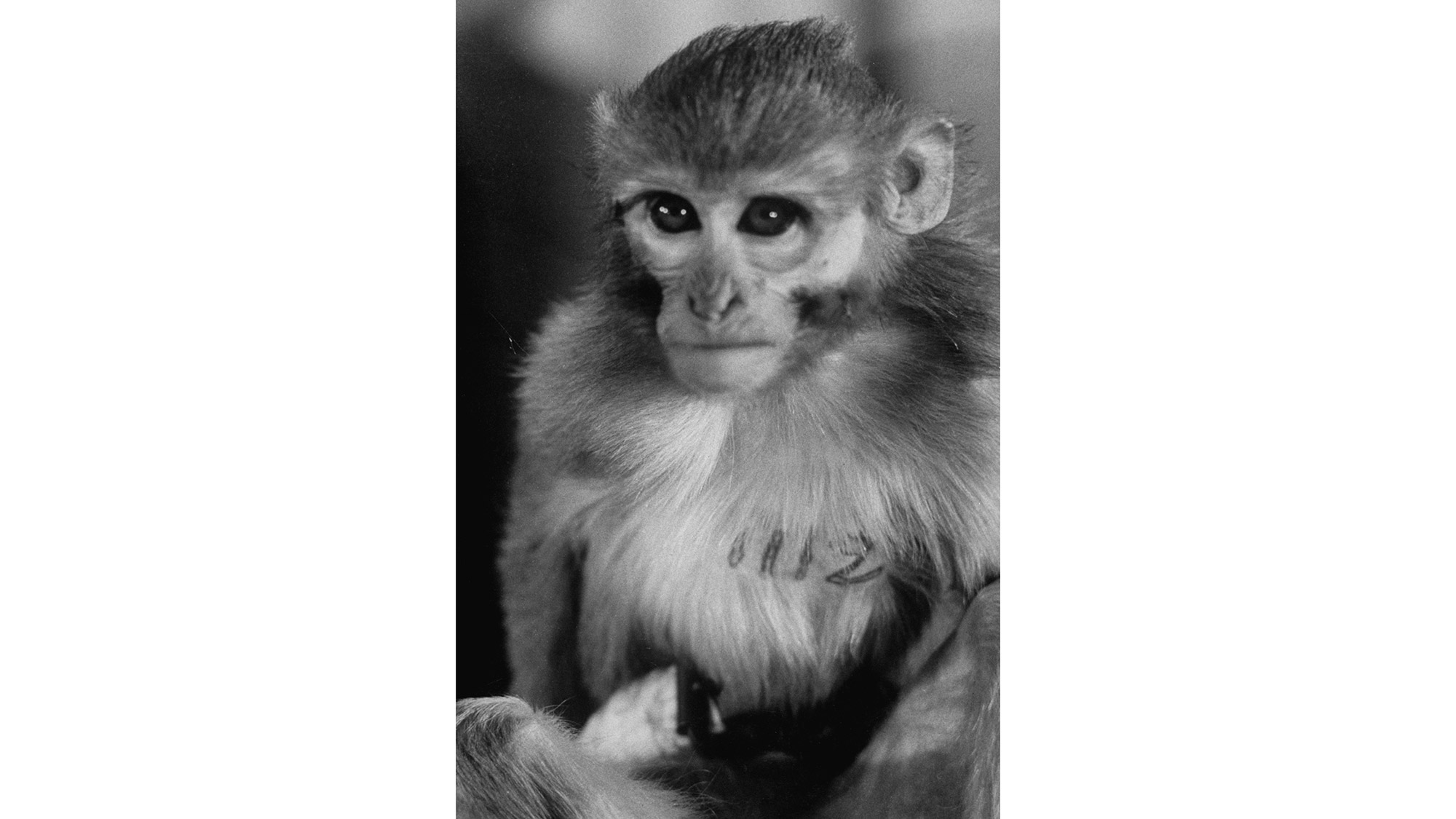

Able was a rhesus monkey. Along with Baker, she became one of the first two primates to survive a spaceflight. During their flight, they reached an altitude of about 300 miles (480 kilometers).

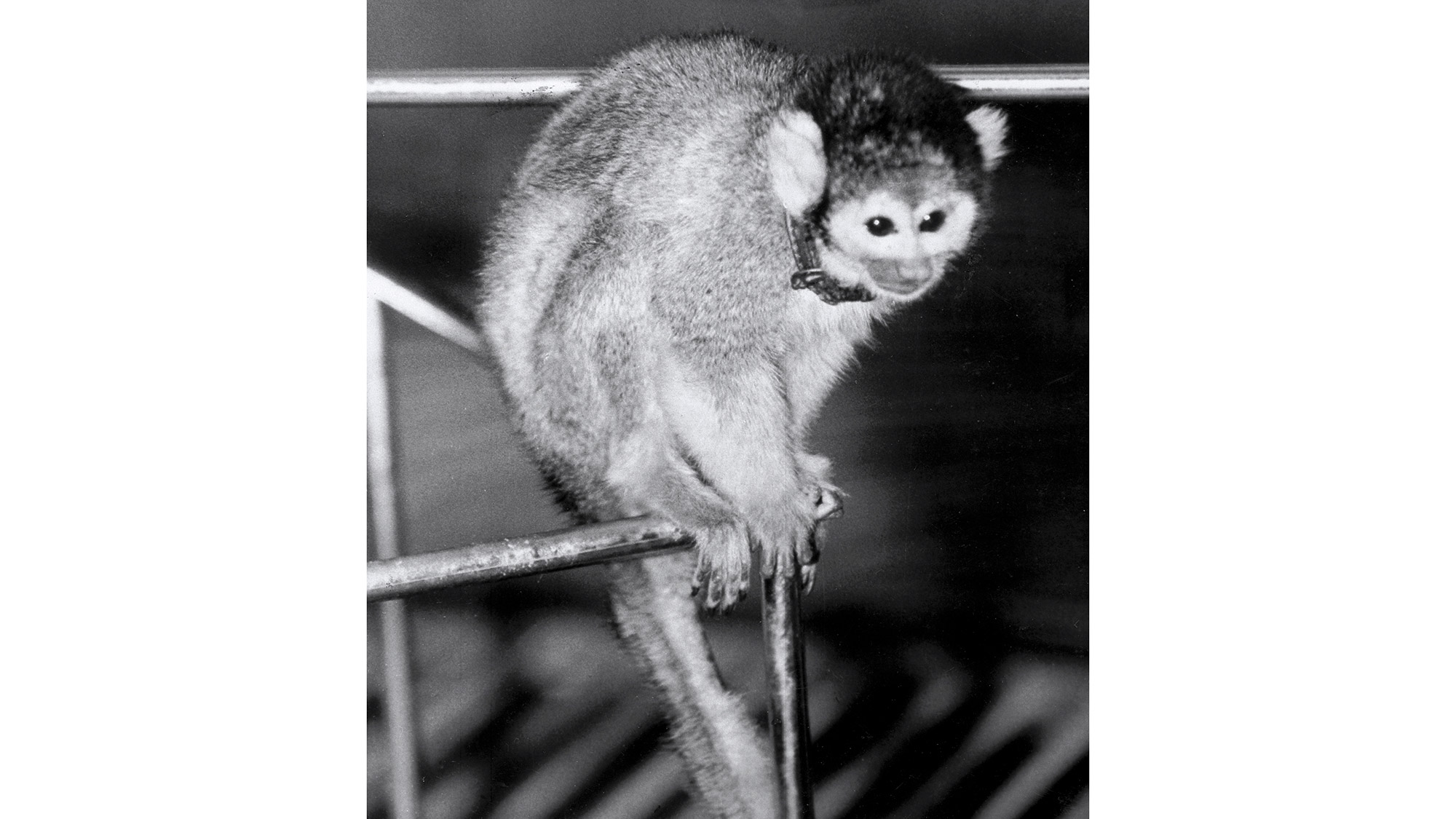

Baker, the squirrel monkey that was the other first primate to survive spaceflight. She and Able were preceded by plenty of attempts at sending monkeys to space, including six consecutive Alberts who were all killed by assorted spaceflight hazards.

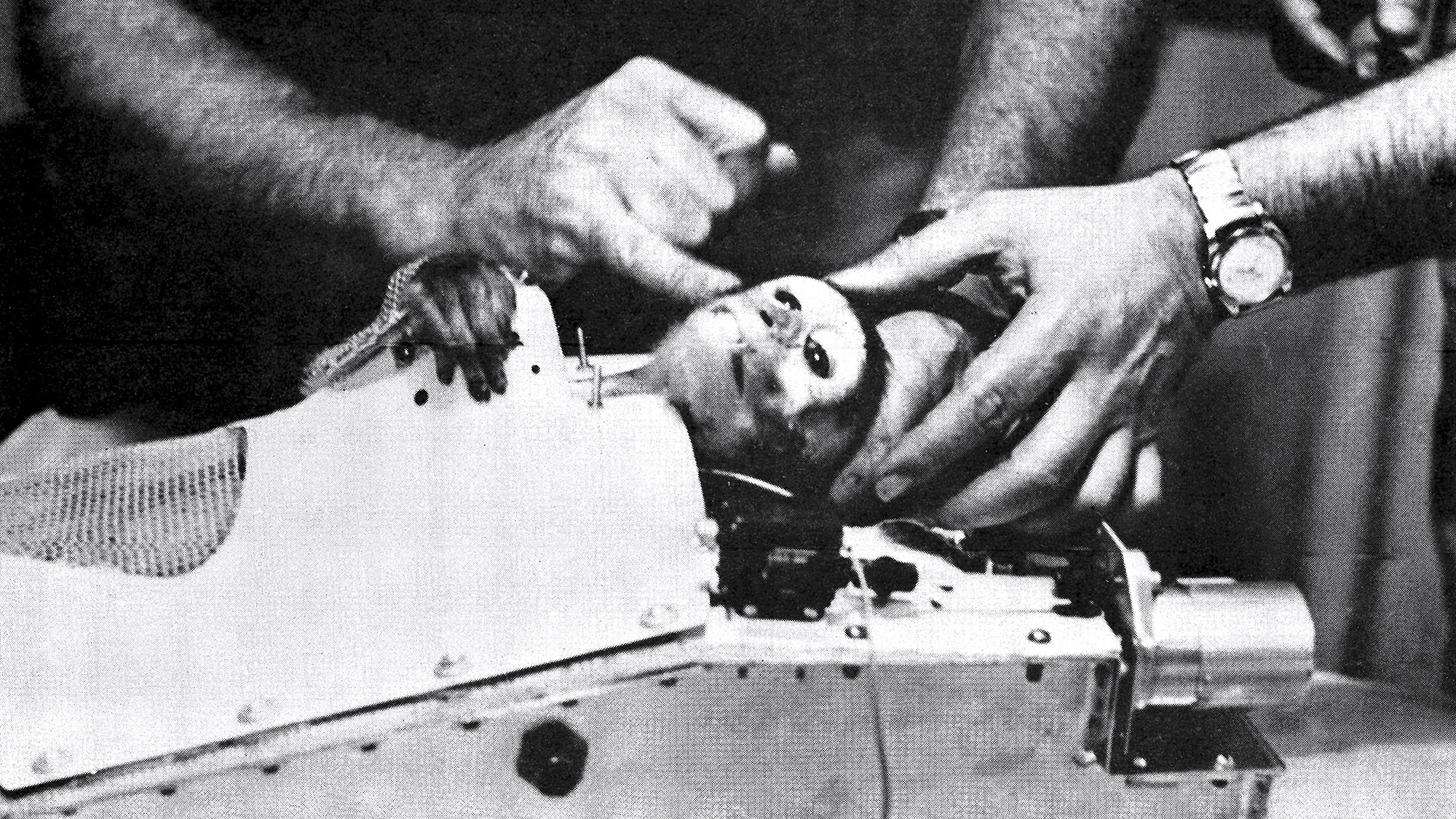

Baker tested out capsules like the one that would carry her to space as early as four weeks before the flight itself.

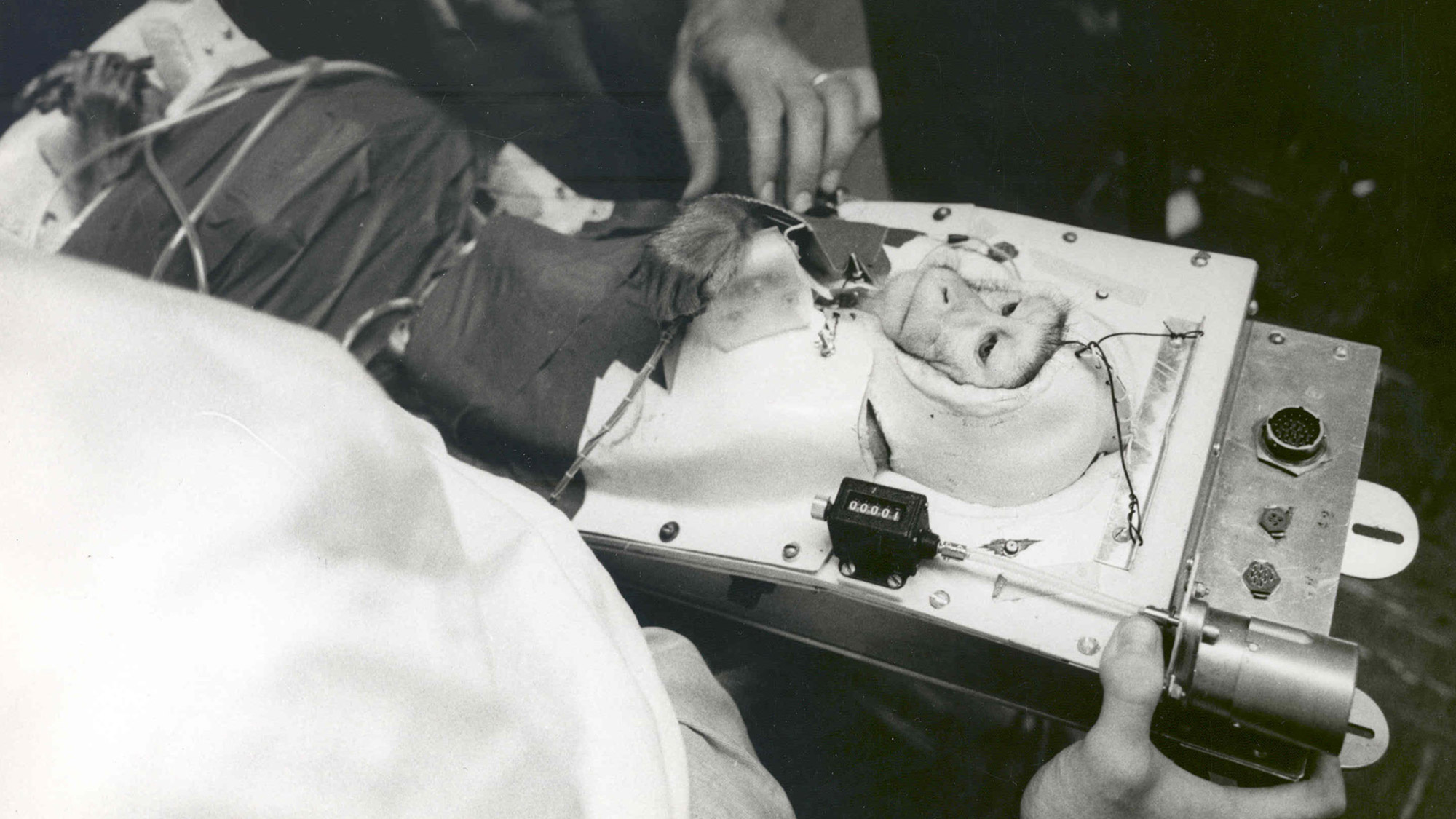

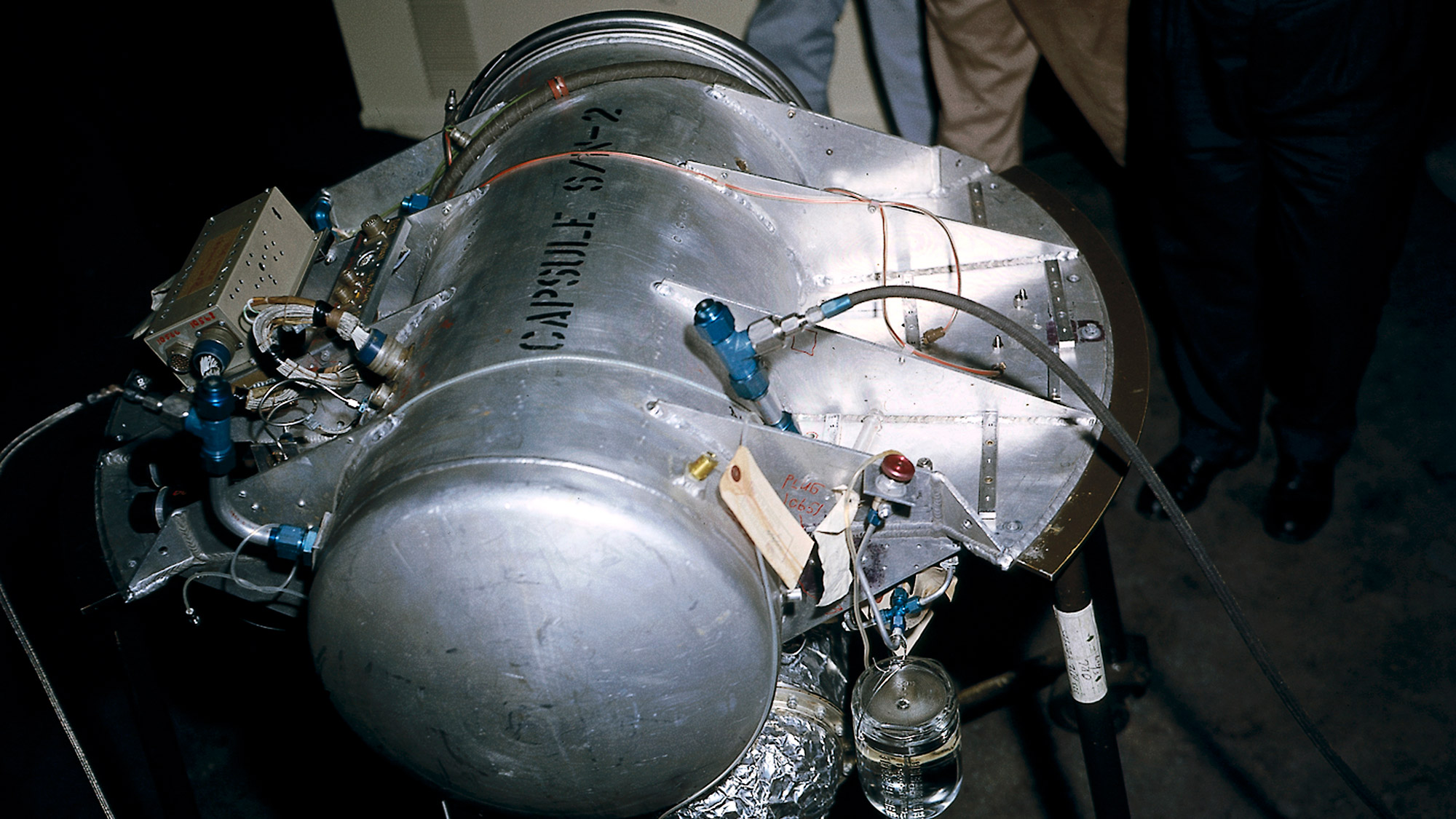

Able also had a specially built capsule for the flight. Each capsule, which is sometimes referred to as a couch, kept the monkey contained and included sensors to monitor their spaceflight experience.

Able, strapped into her flight capsule, as seen in a photograph taken a week and a half before the launch.

Able and Baker's capsule before its insertion into the rocket that would power their flight. Along with the two monkeys, the mission carried yeast cells, blood samples, two frogs, and a range of other biological payloads.

The Jupiter Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile that carried Able and Baker to space. The rocket launched from Florida early in the morning of May 28, 1959.

After their spaceflight, Able and Baker were fished out of the Caribbean by the U.S.S. Kiowa. Here, Able is seen on board that ship as caretakers check her health.

After the U.S.S. Kiowa confirmed the two monkeys were healthy, personnel telegraphed the news back to land. The government had been desperate for any win in the space race, and Able and Baker's safe flight served as just that.

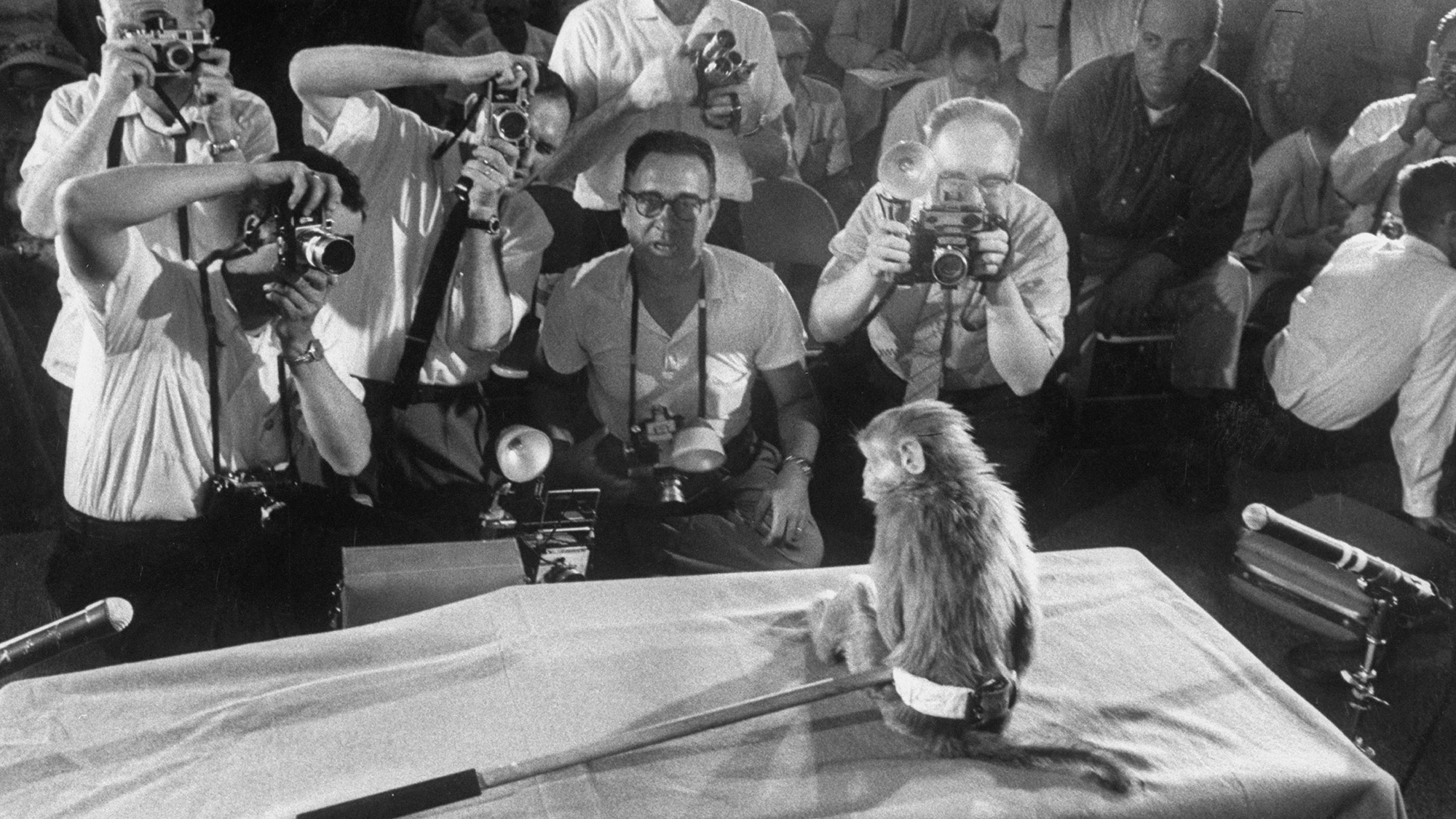

During a news conference held after the two monkeys survived their flight, on June 1, 1959, journalists meet Baker, on the left, and Able, on the right.

Baker, photographed during the news conference showing off the pair of monkey astronauts. The U.S. government was eager to use both monkeys to demonstrate that spaceflight was safe as the country raced the Soviet Union to display supremacy.

The monkeys were unveiled in the same room where NASA had first introduced Alan Shepard, John Glenn and the other Mercury 7 astronauts as their first human candidates for spaceflight just a month before.

Able and Baker during the news conference. Able was a rhesus monkey born in Independence, Kansas; Baker was a much smaller squirrel monkey born in Peru and captured from the wild.

After the news conference, the monkeys' caretakers noticed that one of Able's three electrode sites seemed to be infected. They prepared for a routine surgery to remove it, but when they sprayed Able with a standard anesthetic, she stopped breathing. Doctors spent 2 hours trying to rescue her, including performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. She didn't survive; her body was taxidermied and sent to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

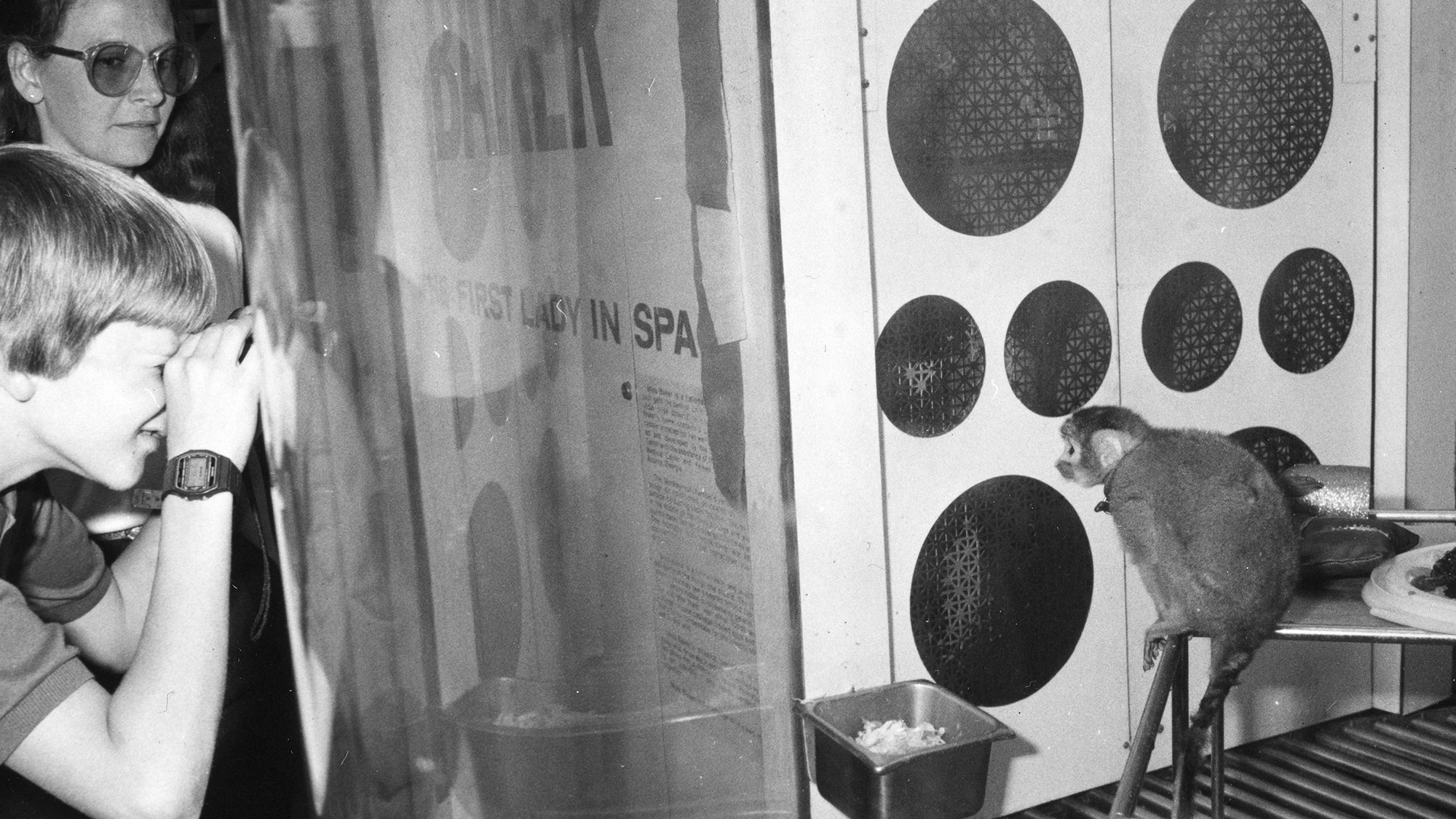

Baker lived to reach 27, which is extreme old age for a squirrel monkey. During her later years, she lived at the Alabama Space and Rocket Center, where she stayed in an enclosure labeled "The First Lady in Space." Her remains are buried on site and marked with a large marble headstone.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.