Two Female Monkeys Went to Space 60 Years Ago. One Became the Poster Child for Astronaut Masculinity

Making history was just the beginning of their story.

Sixty years ago today, a pair of female monkeys made history when they went to space and landed safely — but their story was only just beginning to get weird.

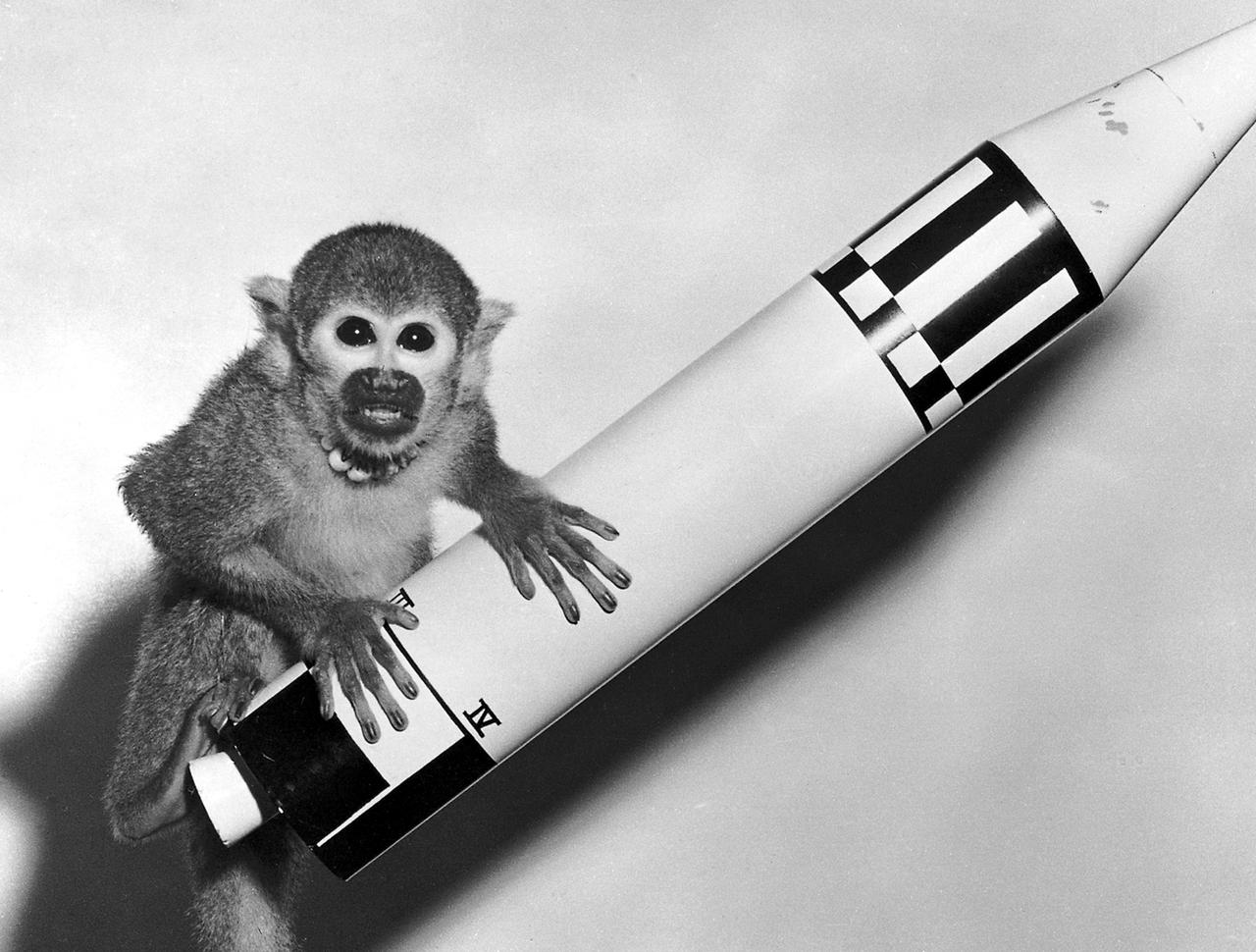

Able and Baker took flight on May 28, 1959, soaring 300 miles (480 kilometers) up during a 15-minute flight. At the time, they were humble female laboratory animals, barely given names for the project before they were stuffed into a Jupiter Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile. By the time the first American human followed them, just two years later, Able was dead, the picture of machismo and sacrifice, while Baker was living in retirement, married off and put on display.

"My whole jam with the history of the astronauts is kind of going one step back in time and going beyond the earliest stories that we know about them," Jordan Bimm, a sociologist at Princeton University who has researched Able and Baker in this context, told Space.com. "Almost nobody remembers the story of Able and Baker, who were actually the first primates to be recovered from a spaceflight."

Related: Able and Baker: The First Primates to Survive Spaceflight in Photos

Before Able, a rhesus monkey, and Baker, a smaller squirrel monkey, faded into obscurity, they were American stars, pawns in a story that became a morass of Cold War stereotypes and symbolism, Bimm argues. "[Their survival] allowed them to perform a sort of PR work and to become, importantly, America's first celebrity space animals," he said.

The mismatched monkeys flew as part of NASA's Bioflight #2 mission, along with payloads ranging from blood samples to yeast cells to two frogs. Their predecessors had met horrifying fates: six consecutive monkeys dubbed Albert and one named Gordo were killed by a variety of spaceflight and recovery hazards. But Able and Baker survived their predawn flight and were fished out of the Caribbean safely, and with two live monkeys in hand, the government's spin machine whipped into overdrive.

"Recovering these animals alive was a huge priority; they really, really, really wanted them both alive," Bimm said. "Getting some wins on the board for America was crucial." Able and Baker were shipped off to Washington, D.C., to be paraded in front of journalists — in the very same room where, just one month earlier, Alan Shepard, John Glenn and their fellow human trainees had been introduced to the world a few weeks earlier.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"From the very, very beginning of human spaceflight, humans selected as astronauts had to contend with animals also going to space," Bimm said. "The only difference is that the monkeys had actually been to space, had actually done the job that the humans were selected to do." It's enough to give even the most swaggering of astronauts an inferiority complex.

But celebrity isn't easy, and that news conference included the first hint of just how weird the story of Able and Baker would get. Gen. Joseph McNinch, who headed the Army's medical research unit, misspoke, using "he" to answer a question about Able. A journalist corrected him and all seemed to be well — but the slip of the tongue began to gain traction. A cartoon Bimm found that was published four days after the flight depicted Able in astronaut garb returning to a harried midcentury monkey wife and baby, the very picture of a jetsetting businessman and absentee father.

Related: Photos: Pioneering Animals in Space

The same day that the cartoon was published, Able died. Caretakers noticed an electrode implanted in her skin seemed infected and prepared to remove it, but when doctors sprayed routine anesthetic in her cage in preparation for the surgery, she stopped breathing. The medical team spent 2 hours attempting to revive her — even performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation — but failed.

After her death, Able was eulogized in obituaries, several of which listed her as male. Her skin was stuffed and sent to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, where she was displayed encased in spaceflight equipment like Han Solo frozen in carbonite. Bimm sees the pose as eternally at work, looking up toward the heavens, hand at her heart.

"Unlike other taxidermy exhibits, where the animal is placed in nature, in this one the animal, Able, is completely surrounded by technology," Bimm said. "It has the sort of valence of the fallen soldier."

Baker, who was often referred to as Miss Baker, survived the postflight hubbub but remained a public icon. For years, she was on display, first at "Baker's Bungalow" in Florida, then at the Alabama Space and Rocket Center, where her enclosure was labeled "The First Lady in Space."

During her retirement, handlers arranged three different "marriages," each heralded with breezy gossip updates. She was thrown birthday parties (despite having been born in the wild) and made to "pawtograph" glamor shots for fans. Baker lived to 27 years old, a record-breaking achievement in and of itself.

(Coincidentally, female pilots spent the first years of Baker's retirement lobbying the government to consider them for astronaut training, with 13 passing all the physical qualifying tests that the Mercury 7 took. Their de facto leader, Jerrie Cobb, endured much of the same media scrutiny and stereotyping as Baker did — and never quite reached space.)

Related: Pioneering Animals in Space: A Gallery

Ironically, before their flight, most of the hubbub around Able and Baker's identity was focused on where the monkeys were born — Baker in Peru and Able in Independence, Kansas. (Able's species is venerated in India and so the government insisted on an American monkey to avoid upsetting the geopolitically important country.)

But just days after their flight, that rubric was forgotten, erased by a new one. "There's sort of a male/female, masculine/feminine, work and domesticity binary in operation," Bimm said. The dead/alive binary he left unspoken, but for years it separated Able and Baker as well.

Until Baker, too, died and was buried below a massive marble headstone inscribed to "Miss Baker, squirrel monkey … First U.S. animal to fly in space and return alive." Bimm has visited both Able's display and Baker's memorial. "It was moving," Bimm said. "As a historian, you become really attached to your subjects and a lot of the times my subjects are quite evil people, they're ex-Nazi scientists who come to America and work for the space program, but in the case of Able and Baker, they're these innocent animals."

People still visit both monkeys — some leave bananas at Baker's grave. But by the time the pair had died, the space program had moved on, and so had space fans. The first space shuttle had launched in 1981, and soon enough the country had humans to mourn, not just monkeys, after the Challenger broke apart shortly after launch in 1986. "The shuttle era had its own tragedies, human tragedies," Bimm said. "Those really served to displace, I think, a lot of the narratives about space."

But Bimm argues that Able and Baker's wild story offers important reminders of the baggage that comes with spaceflight — gender stereotypes and sex discrimination, jingoism and missile programs, ex-Nazis and animal cruelty among them. All of those undercurrents continue to haunt the U.S. space program.

"I hope people see it as a story, as something constructed in the minds of humans, and I hope they see for all animals in spaceflight research that these are unwilling participants," Bimm said. That's especially true because spaceflight research on animals continues to this day and has already been discussed in the context of future Mars exploration. "We need to talk about them realistically and not create these fables and fantasies that paper over the truth."

- Cosmic Menagerie: A History of Animals in Space (Infographic)

- Monkeys in Space: A Brief Spaceflight History

- How Space Exploration Can Teach Us to Preserve All Life on Earth

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.