After 17 years away, NASA's sun-studying spacecraft will visit Earth on Aug. 12

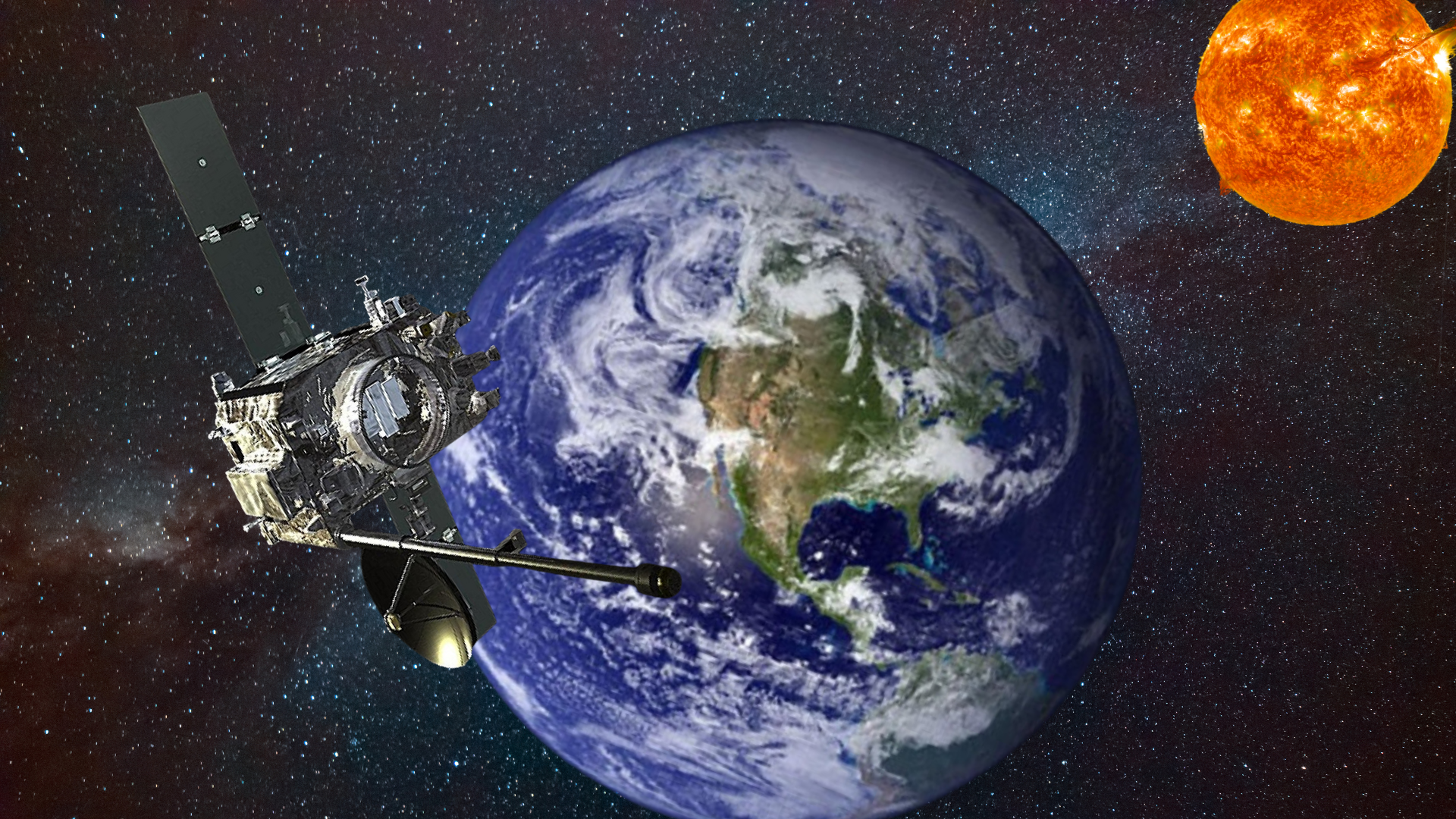

The STEREO-A spacecraft will pass between Earth and the sun this weekend, getting the chance to team up with other NASA missions.

A groundbreaking NASA spacecraft will return to Earth on Saturday (Aug. 12) after 17 years away from home.

One-half of the agency's STEREO (Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory) mission, STEREO-A will fly close to our planet for the first time since its launch on Oct. 25, 2006, from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. STEREO-A will pass between Earth and the sun this weekend.

STEREO-A is the lead component of a dual-spacecraft mission, which also includes the STEREO-B spacecraft. This was the first mission to capture a multiple-perspective or "stereoscopic" view of the sun. The STEREO mission also made history in February of 2011, when the two spacecraft achieved a 180-degree separation in their orbital pathway, taking positions on opposite sides of the sun and offering humanity its first glimpse of our star as a complete sphere. Akin to their titles, STEREO-A's "A" stands for "ahead" and STEREO-B's "B" stands for "behind."

"Prior to that, we were 'tethered' to the sun-Earth line — we only saw one side of the sun at a time," STEREO program scientist, Lika Guhathakurta, said in a statement. "STEREO broke that tether and gave us a view of the sun as a three-dimensional object."

Related: Sun blasts out highest-energy radiation ever recorded, raising questions for solar physics

The STEREO mission had achieved a number of other scientific feats since leaving Earth 17 years ago, and both spacecraft were providing views of space until STEREO-B broke contact with mission control in 2014 after a planned reset (B's mission officially ended in 2018). STEREO-A, however, has remained in contact with Earth since the loss of its compatriot, and this brief return home won't see it rest on its laurels.

Instead, the spacecraft will team up with some newer NASA missions during its visit.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By synthesizing its view of the sun with the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), STEREO-A will once again provide a stereoscopic 3D picture of our host star, just like it used to with STEREO-B. The fact that STEREO-A will be changing its distance from Earth during its visit also means it'll be able to offer views of solar features with differing sizes. This would be kind of like changing the focus of a telescope with a million-mile-wide field of view.

That should allow researchers to make vital solar measurements, identify active regions of the sun and even obtain 3D information about complex magnetic structures underlying sunspots. These structures are usually unavailable for study with 2D imagery.

Further, this visit by STEREO-A could help solar physicists decode some longstanding mysteries regarding the sun. "There is a recent idea that coronal loops might just be optical illusions," STEREO project scientist, Terry Kucera, said.

This refers to the fact that some scientists have suggested our limited viewing angles of massive bands of plasma emerging from the sun make them appear to have shapes they may not truly have. "If you look at them from multiple points of view, that should become more apparent," Kucera added.

Star I used to know...

STEREO-A won't just be collecting visual data as it makes its flyby of Earth over the weekend. The spacecraft will also feel eruptions from our star, called coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

When blasted out into space, these massive plumes of charged particles can disrupt satellites orbiting Earth, interfere with radio signals across the planet and even damage power infrastructure. The influence of CMEs, in terms of whether they cause damage or disruption upon reaching Earth, is dictated by magnetic fields carried along with them. These fields can change dramatically as the charged particles cross the 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) of space between the sun and Earth.

Scientists can build models of CMEs and their magnetic fields, but these models are limited when observations come from a single spacecraft.

"It's like the parable about the blind men and the elephant — the one who feels the legs says 'it’s like a tree trunk,' and the one who feels the tail says 'it’s like a snake,'" University of New Hampshire professor and principal investigator for one of STEREO-A’s instruments, Toni Galvin, said. "That's what we're stuck with right now with CMEs, because we typically only have one or two spacecraft right next to each other measuring it."

In the months before it flies by our planet, STEREO-A has been collecting data about Earth-directed CMEs — and it will continue to do this for months after it leaves our planet's vicinity again. As it has been doing this, so have other near-Earth spacecraft. Put together, these datasets should give solar scientists different views of the same CMEs, revealing the ejections' magnetic innards.

It won't be all familiar territory when STEREO-A returns to Earth.

Last time the NASA craft was so close to our planet, in 2006, the sun was in a phase called "solar minimum." This means is was in a relatively quiet phase, with little activity and few sunspots.

By contrast, the sun STEREO-A will see this weekend is approaching a period of solar maximum in its roughly 11-year cycle, which should peak in 2025.

"The sun was so quiet at that point! I was looking back at the data, and I said, 'Oh yeah, I recognize that active region’ — there was one, and we studied it," Kucera said, "OK, it wasn’t quite that bad — but it was close."

That means that STEREO-A will experience a "fundamentally different" star than it did some 17 years ago. "There is so much knowledge to be gained from that," Guhathakurta concluded.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.