AI algorithm discovers 'potentially hazardous' asteroid 600 feet wide in a 1st for astronomy

A potentially dangerous space rock was discovered for the first time by an AI algorithm.

A new artificial intelligence algorithm programmed to hunt for potentially dangerous near-Earth asteroids has discovered its first space rock.

The roughly 600-foot-wide (180 meters) asteroid has received the designation 2022 SF289, and is expected to approach Earth to within 140,000 miles (225,000 kilometers). That distance is shorter than that between our planet and the moon, which are on average, 238,855 miles (384,400 km) apart. This is close enough to define the rock as a Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (PHA), but that doesn't mean it will impact Earth in the foreseeable future.

The HelioLinc3D program, which found the asteroid, has been developed to help the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, currently under construction in Northern Chile, conduct its upcoming 10-year survey of the night sky by searching for space rocks in Earth's near vicinity. As such, the algorithm could be vital in giving scientists the heads up about space rocks on a collision course with Earth.

"By demonstrating the real-world effectiveness of the software that Rubin will use to look for thousands of yet-unknown potentially hazardous asteroids, the discovery of 2022 SF289 makes us all safer," Vera C. Rubin researcher Ari Heinze said in a statement.

Related: Super-close supernova captivates record number of citizen scientists

Tens of millions of space rocks roam the solar system ranging from asteroids the size of a few feet to dwarf planets around the size of the moon. These space rocks are the remains of material that initially formed the planets around 4.5 billion years ago.

While most of these objects are located far from Earth, with the majority of asteroids homed in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, some have orbits that bring them close to Earth. Sometimes worryingly close.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space rocks that come close to Earth are defined as near-Earth objects (NEOs), and asteroids that venture to within around 5 million miles of the planet get the Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (PHA) status. This doesn't mean that they will impact the planet, though. Just as is the case with 2022 SF289, no currently known PHA poses an impact risk for at least the next 100 years. Astronomers search for potentially hazardous asteroids and monitor their orbits just to make sure they are not heading for a collision with the planet.

This new PHA was found when the asteroid-hunting algorithm was paired with data from the ATLAS survey in Hawaii, as a test of its efficiency before Rubin is completed.

The discovery of 2022 SF289 has shown that HelioLinc3D can spot asteroids with fewer observations than current space rock hunting techniques allow.

Rubin is ready to join the potentially hazardous asteroid hunt

Searching for potentially hazardous asteroids involves taking images of parts of the sky at least four times a night. When astronomers spot a moving point of light traveling in an unambiguous straight line across the series of images, they can be quite certain they have found an asteroid. Further observations are then made to better constrain the orbit of these space rocks around the sun.

The new algorithm, however, can make a detection from just two images, speeding up the whole process.

Around 2,350 PHAs have been discovered thus far, and though none poses a threat of hitting Earth in the near future, astronomers aren't quite ready to relax just yet as they know that many more potentially dangerous space rocks are out there yet to be uncovered.

It is estimated that the Vera Rubin Observatory could uncover as many as 3,000 hitherto undiscovered potentially hazardous asteroids.

Rubin's 27-foot-wide (8.4 meters) mirror and massive 3,200-megapixel camera will revisit locations in the night sky twice per night rather than the four times a night observations conducted by current telescopes. Hence the creation of HelioLinc3D, a code that could find asteroids in Rubin's dataset even with fewer available observations.

But, the algorithm's creators wanted to give the software a trial run before the construction of Rubin is completed. This meant testing if it could find an asteroid in data that had already been collected, data that has too few observations for currently employed algorithms to scour.

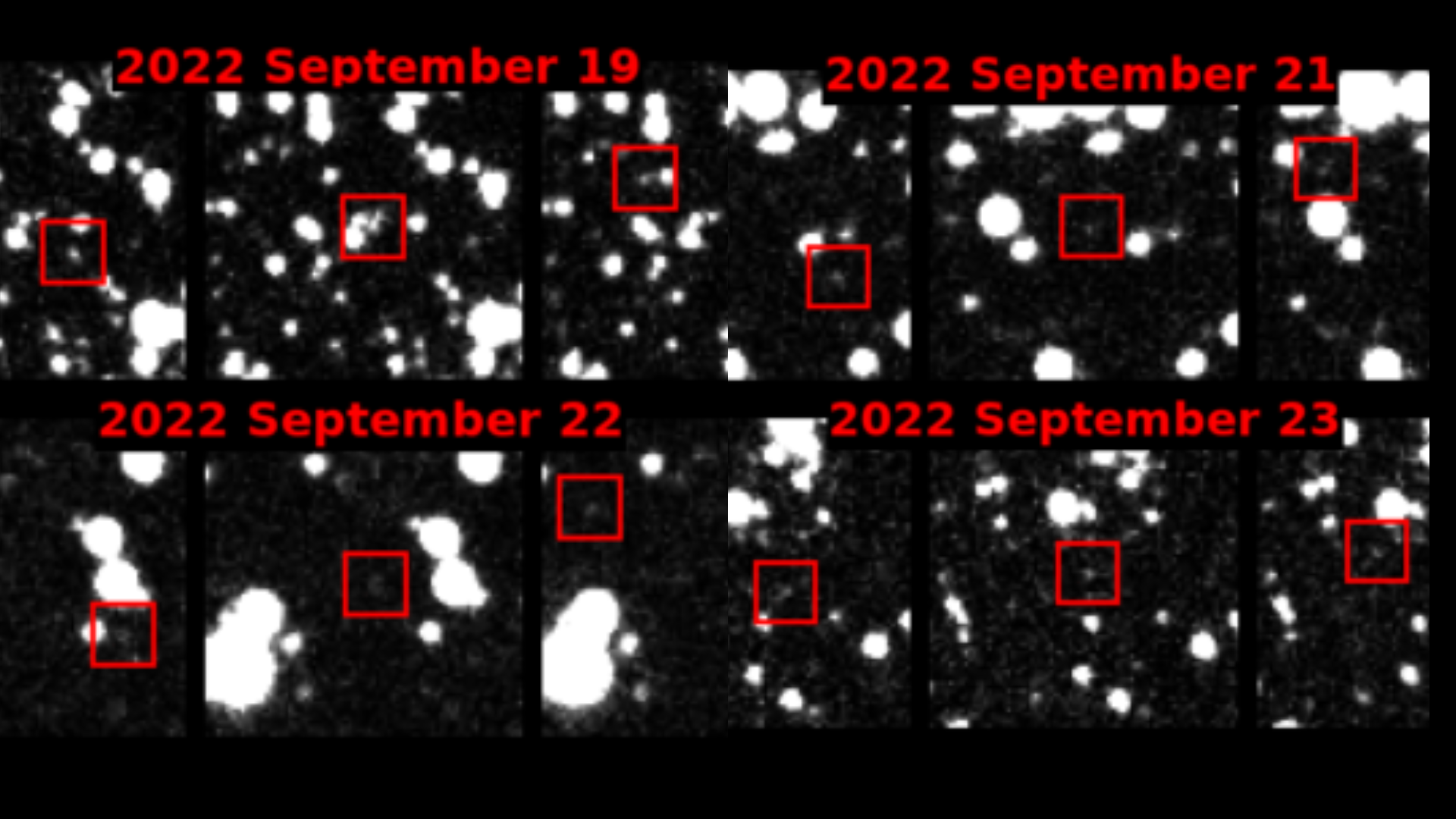

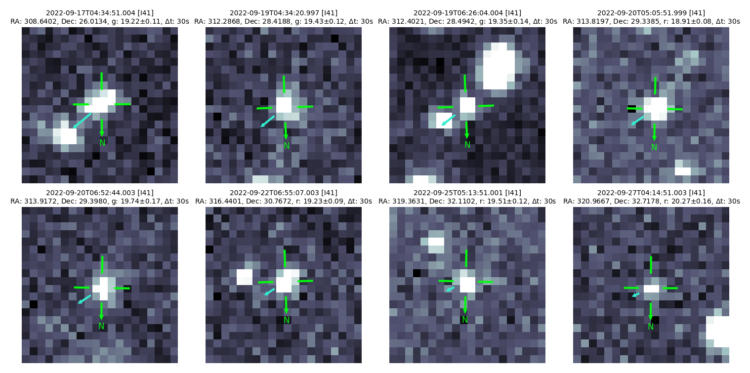

With ATLAS data offered as such a test subject, HelioLinc3D set about looking for PHAs, and on July 18, 2023, it hit paydirt, uncovering 2022 SF289. This PHA was spotted by ATLAS on September 19, 2022, while it was 3 million miles from Earth. ATLAS had actually spotted this new PHA three times over the course of four nights but hadn't spotted it four times in the same night, meaning current surveys missed it. By putting together fragments of data from all four nights, HelioLinc3D was able to identify the PHA.

"Any survey will have difficulty discovering objects like 2022 SF289 that are near its sensitivity limit, but HelioLinc3D shows that it is possible to recover these faint objects as long as they are visible over several nights," lead ATLAS astronomer Larry Denneau said. "This in effect gives us a 'bigger, better' telescope."

With the position of 2022 SF289 pinpointed, astronomers could then follow up on the discovery with other telescopes to confirm the PHA's existence.

"This is just a small taste of what to expect with the Rubin Observatory in less than two years when HelioLinc3D will be discovering an object like this every night," Rubin scientist and HelioLinc3D team leader Mario Jurić said. "But more broadly, it's a preview of the coming era of data-intensive astronomy. From HelioLinc3D to AI-assisted codes, the next decade of discovery will be a story of advancement in algorithms as much as in new, large, telescopes."

The discovery of 2022 SF289 was announced in the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Electronic Circular MPEC 2023-O26.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.