Alien rain isn't as foreign as you might expect.

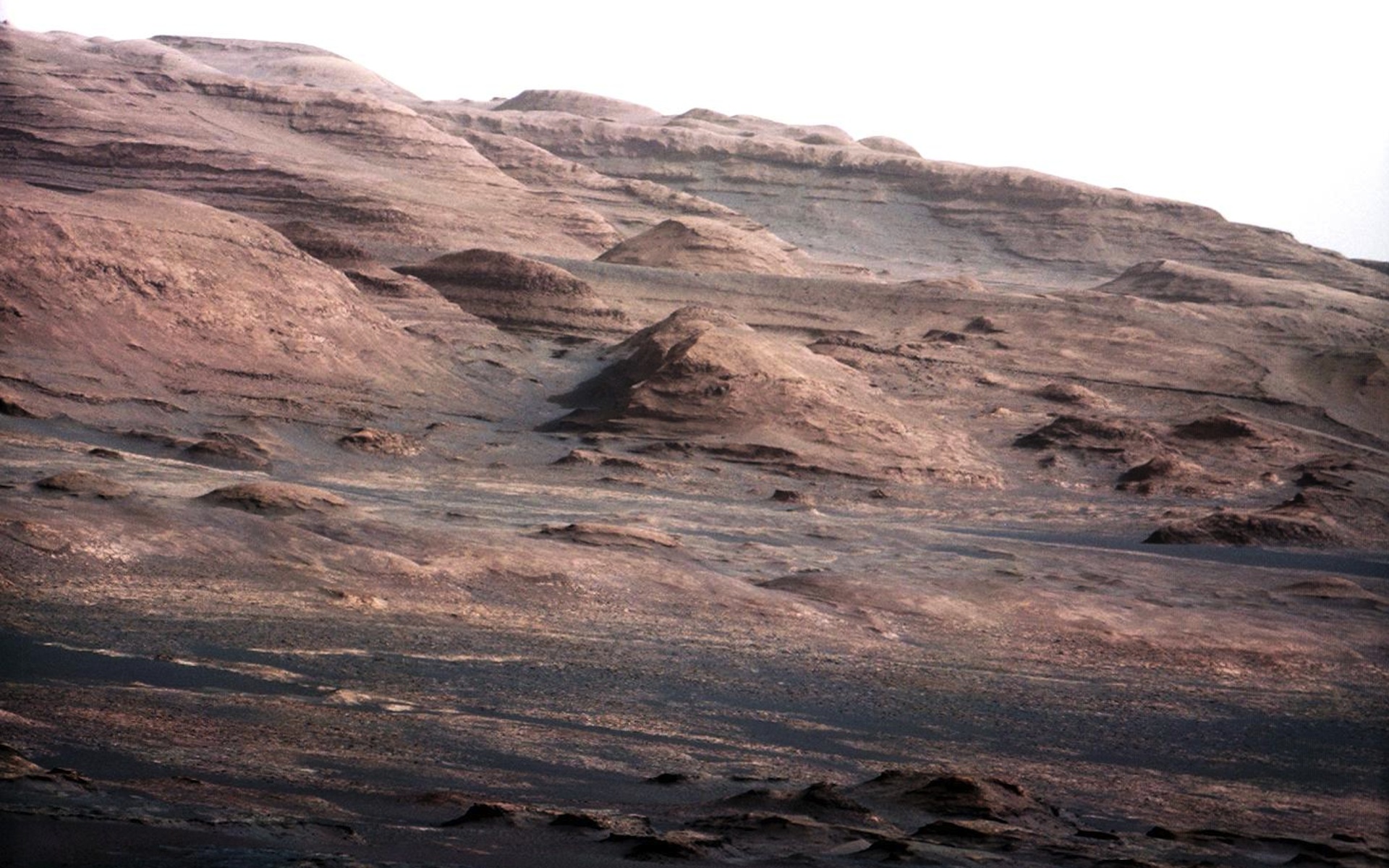

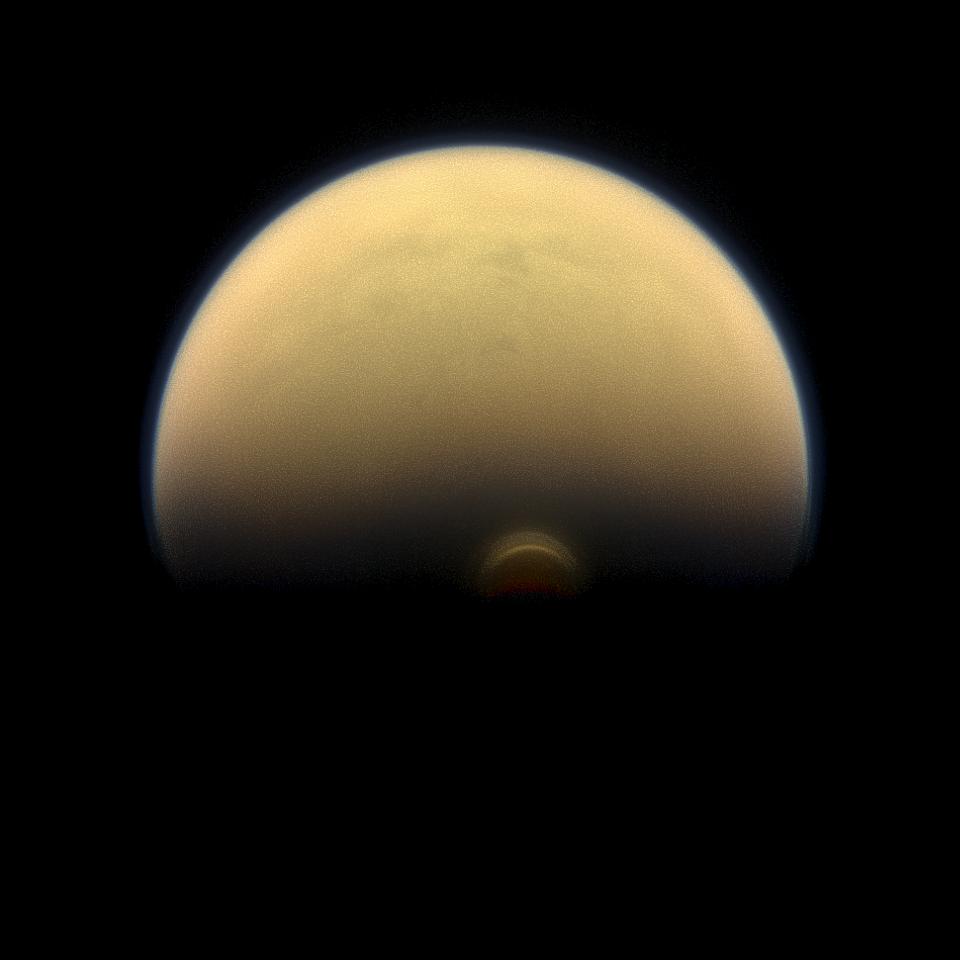

Showers on other worlds can definitely be exotic. On Saturn's huge moon Titan, for example, liquid hydrocarbons fall through the skies, course down river channels and fill big lakes and seas.

But those Titanian methane droplets — and the sulfuric acid globules that fall on Venus and the liquid helium that makes up Jupiter's rain — are actually broadly similar to the raindrops that splash down here on Earth, a new study suggests.

Related: The strangest alien planets (images)

"There’s a fairly small range of stable sizes that these different-composition raindrops can have; they’re all fundamentally limited to be around the same maximum size," lead author Kaitlyn Loftus, a graduate student in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University, said in a statement.

Loftus and co-author Robin Wordsworth, an associate professor of environmental science and engineering at Harvard, modeled how rain falls through the atmospheres of planets and moons of various sizes, temperatures and compositions.

The researchers found that maximum droplet size doesn't vary much from world to world. For example, the biggest Titan raindrops are less than three times larger than the biggest drops here on Earth — around 1.2 inches (3.0 centimeters) wide versus roughly 0.44 inches (1.1 cm).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In addition, Loftus and Wordsworth calculated that, on rocky planets, only cloud droplets in a narrow size range can end up splashing down on the ground. Those cloud droplets must have a radius between roughly 0.1 millimeters to a few millimeters, no matter what they're made of, or they won't make it to the surface. (There are 10 millimeters in a centimeter, which equates to about 2.54 inches.)

The new study, which was published online last month in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, could help researchers model the climate cycles of exoplanets and worlds much closer to home, team members said.

"The insights we gain from thinking about raindrops and clouds in diverse environments are key to understanding exoplanet habitability," Wordsworth said in a different statement. "In the long term, they can also help us gain a deeper understanding of the climate of Earth itself."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.