How big is the universe?

How big is the universe around us? What we can observe gives us an answer, but it's likely much bigger than that.

How big is the universe? It's one of the fundamental questions of astronomy. By looking for the farthest observable point from Earth (and by extension, the oldest given the speed of light) we can estimate a diameter.

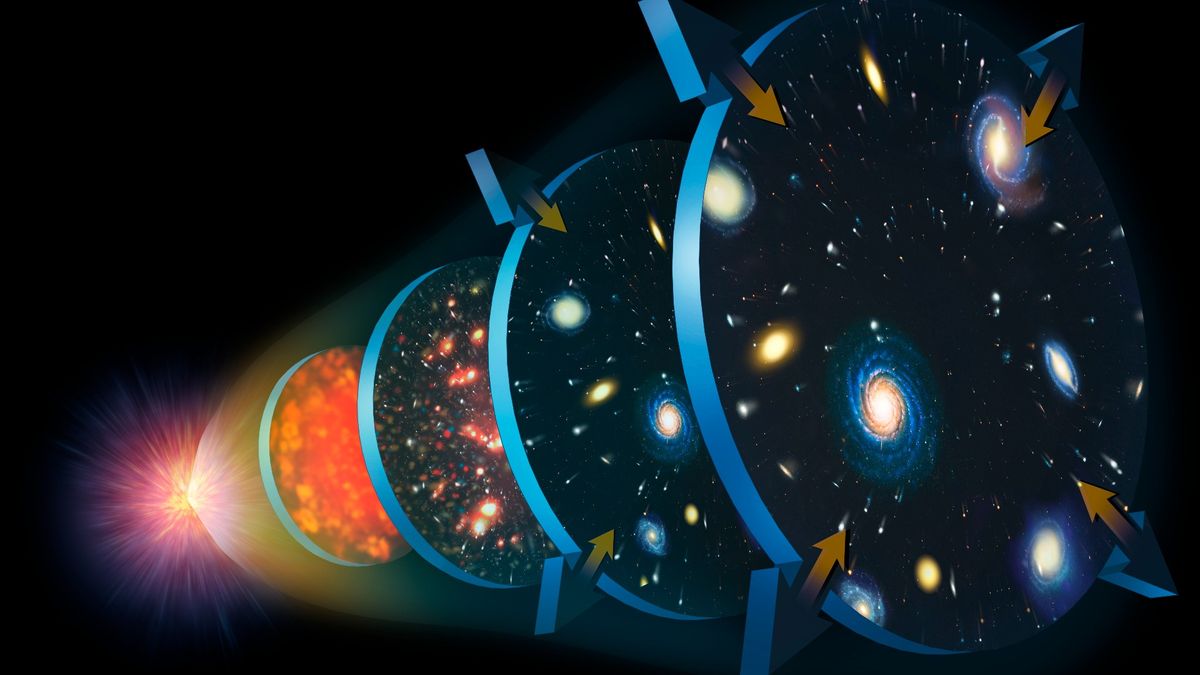

Thanks to evolving technology, astronomers are able to look back in time to the moments just after the Big Bang. This might seem to imply that the entire universe lies within our view. But the size of the universe depends on a number of things, including its shape and expansion.

As a result, while we can make estimates as to the size of the universe scientists can't put a number on it.

Related: What is the coldest place in the universe?

The observable universe

In 2013, the European Space Agency's Planck space mission released the most accurate and detailed map ever made of the universe's oldest light. The map revealed that the universe is 13.8 billion years old. Planck calculated the age by studying the cosmic microwave background.

"The cosmic microwave background light is a traveler from far away and long ago," said Charles Lawrence, the U.S. project scientist for the mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, in a statement. "When it arrives, it tells us about the whole history of our universe."

Because of the connection between distance and the speed of light, this means scientists can look at a region of space that lies 13.8 billion light-years away. Like a ship in the empty ocean, astronomers on Earth can turn their telescopes to peer 13.8 billion light-years in every direction, which puts Earth inside of an observable sphere with a radius of 13.8 billion light-years. The word "observable" is key; the sphere limits what scientists can see but not what is there.

But though the sphere appears almost 28 billion light-years in diameter, it is far larger. Scientists know that the universe is expanding. Thus, while scientists might see a spot that lay 13.8 billion light-years from Earth at the time of the Big Bang, the universe has continued to expand over its lifetime. If inflation occurred at a constant rate through the life of the universe, that same spot is 46 billion light-years away today according to Ethan Siegel, writing for Forbes, making the diameter of the observable universe a sphere around 92 billion light-years.

These estimations are further complicated by the possibility that the universe is not expanding in an even manner. ESA reported on a 2020 study using data from ESA’s XMM-Newton, NASA’s Chandra Space Telescope and Rosat X-ray observatories suggests that the universe is not expanding at the same rate in all directions. The study measured the X-ray temperatures of hundreds of galaxy clusters and compared that against their brightness. Some clusters appeared less bright than expected, suggesting they were not moving at the same rate. "This possibly uneven effect on cosmic expansion might be caused by the mysterious dark energy," ESA stated.

Centering a sphere on Earth's location in space might seem to put humans in the center of the universe. However, like that same ship in the ocean, we cannot tell where we lie in the enormous span of the universe. Just because we cannot see land does not mean we are in the center of the ocean; just because we cannot see the edge of the universe does not mean we lie in the center of the universe.

Measuring the universe

Scientists measure the size of the universe in a myriad of different ways. They can measure the waves from the early universe, known as baryonic acoustic oscillations, that fill the cosmic microwave background. They can also use standard candles, such as type 1A supernovae, to measure distances. However, these different methods of measuring distances can provide answers.

How inflation is changing is also a mystery. While the estimate of 92 billion light-years comes from the idea of a constant rate of inflation, many scientists think that the rate is slowing down. If the universe expanded at the speed of light during inflation, it should be 10^23, or 100 sextillion. One explanation for this, outlined by NASA in 2019, is that dark energy events may have impacted the expansion of the universe in the moments after the Big Bang.

Instead of taking one measurement method, a team of scientists led by Mihran Vardanyan at the University of Oxford did a statistical analysis of all of the results. By using Bayesian model averaging, which focuses on how likely a model is to be correct given the data, rather than asking how well the model itself fits the data. They found that the universe is at least 250 times larger than the observable universe, or at least 7 trillion light-years across.

"That's big, but actually more tightly constrained that many other models," according to 2011 MIT Technology Review report.

Related stories:

– Phantom energy and dark gravity: Explaining the dark side of the universe

– Do parallel universes exist? We might live in a multiverse

– Geocentric model: The Earth-centered view of the universe

The shape of the universe

The size of the universe depends a great deal on its shape. Scientists have predicted the possibility that the universe might be closed like a sphere, infinite and negatively curved like a saddle, or flat and infinite.

A finite universe has a finite size that can be measured; this would be the case in a closed spherical universe. But an infinite universe has no size by definition.

According to NASA, scientists know that the universe is flat with only about a 0.4 percent margin of error (as of 2013). And that could change our understanding of just how big the universe is.

"This suggests that the universe is infinite in extent; however, since the universe has a finite age, we can only observe a finite volume of the universe," says NASA . "All we can truly conclude is that the universe is much larger than the volume we can directly observe."

Determining the shape of the universe presents further challenges thanks to the limits of our means of observation. "Like a hall of mirrors, the apparently endless universe might be deluding us. The cosmos could, in fact, be finite. The illusion of infinity would come about as light wrapped all the way around space, perhaps more than once—creating multiple images of each galaxy," according to the University of Oregon department of physics.

Additional resources and reading

There are plenty more questions about the universe you might want to have answered, such as what if the universe didn't have a beginning? If your thirst for universal knowledge needs more, then these 10 wild theories about the universe might get your mind racing as well.

Bibliography

"Planck Mission Explores the History of Our Universe" NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

"How Big Was The Universe At The Moment Of Its Creation?" Forbes

"The Universe Might Not Be Expanding At The Same Rate Everywhere" ESA

"Mystery of the Universe's Expansion Rate Widens With New Hubble Data" NASA

"Cosmos At Least 250x Bigger Than Visible Universe, Say Cosmologists" MIT Technology Review

"The Universe Is Flat — Now What?" Space.com

"Will the Universe expand forever?" NASA

"Geometry of the Universe" University of Oregon department of physics

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd