Artemis Accords: why many countries are refusing to sign moon exploration agreement

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Christopher Newman, Professor of Space Law and Policy, Northumbria University, Newcastle

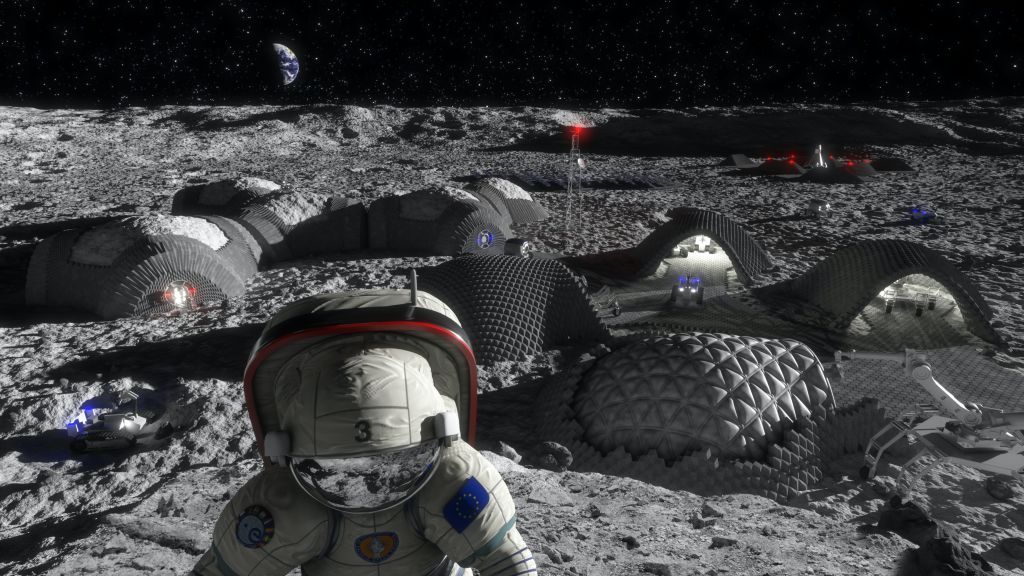

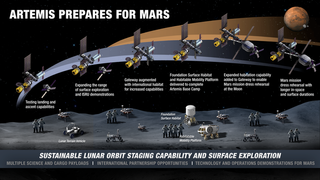

Eight countries have signed the Artemis Accords, a set of guidelines surrounding the Artemis Program for crewed exploration of the moon. The United Kingdom, Italy, Australia, Canada, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates and the US are now all participants in the project, which aims to return humans to the moon by 2024 and establish a crewed lunar base by 2030.

This may sound like progress. Nations have for a number of years struggled with the issue of how to govern a human settlement on the moon and deal with the management of any resources. But a number of key countries have serious concerns about the accords and have so far refused to sign them.

Previous attempts to govern space have been through painstakingly negotiated international treaties. The Outer Space Treaty 1967 laid down the foundational principles for human space exploration – it should be peaceful and benefit all mankind, not just one country. But the treaty has little in the way of detail. The moon Agreement of 1979 attempted to prevent commercial exploitation of outer-space resources, but only a small number of states have ratified it – the US, China and Russia haven’t.

Now that the US is pursuing the Artemis Program, the question of how states will behave in exploring the moon and using its resources has come to a head. The signing of the accords represents a significant political attempt to codify key principles of space law and apply them to the program. You can hear more about some of the governance issues facing nations who want to explore the moon in the podcast To the moon and beyond, see link below.

The accords are bilateral agreements and not binding instruments of international law. But by establishing practice in the area, they could have a significant influence on any subsequent governance framework for human settlements on Mars and beyond.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Natural allies

All seven partners who have agreed to the accords with the US are natural collaborators on the Artemis Program and will easily adhere to the stated principles. Japan is keen to engage in lunar exploration. Luxembourg has dedicated legislation allowing for space mining and has also signed an additional collaborative agreement with the US.

The UAE and Australia are both actively trying to establish collaborative links with the broader space industry, so this represents a perfect opportunity for them to build up capacity. Italy, the UK and Canada all have ambitions to develop their space manufacturing industries and will see this as a chance to grow their economies.

The contents of the accords are relatively uncontentious. Throughout, there is reference to the existing Outer Space Treaty framework, so they are tied closely to existing norms of space law. As such, the accords appear deliberately designed to reassure countries that this is not an instruction on how to behave from a hegemonic power.

There is an explicit statement that the mining of space resources is in accordance with international law. This follows on from the controversial passing of the Space Act 2015, which put the right to use and trade space resources into American domestic law. But section 10(4) of the accords also commits to ongoing discussions at the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space as to how the legal framework should develop.

The rest of the accords focus on safety in space operations, transparency and interoperability (which refers to the ability of space systems to work in conjunction with each other).

Controversial issues

If the substance is reassuring, the US promotion of the accords outside of the "normal" channels of international space law – such as the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space – will be a cause of consternation for some states. By requiring potential collaborators to sign bilateral agreements on behavior instead, some nations will see the US as trying to impose their own quasi-legal rules. This could see the US leveraging partnership agreements and lucrative financial contracts to reinforce its own dominant leadership position.

Russia has already stated that the Artemis Program is too "US-centric" to sign it in its present form. China’s absence is explained by the US congressional prohibition on collaboration with the country. Concerns that this is a power grab by the US and its allies are fueled by the lack of any African or South American countries amongst the founding partner states.

Intriguingly Germany, France and India are also absent. These are countries with well developed space programs that would surely have benefited from being involved in Project Artemis. Their opposition may be down to a preference for the moon Agreement and a desire to see a properly negotiated treaty governing lunar exploration.

The European Space Agency (ESA) as an organization has not signed on to the accords either, but a number of ESA member states have. This is unsurprising. The ambitious US deadline for the project will clash with the lengthy consultation of the 17 member states required for the ESA to sign on as a whole.

Ultimately, the Artemis Accords are revolutionary in the field of space exploration. Using bilateral agreements that dictate norms of behavior as a condition of involvement in a program is a significant change in space governance. With Russia and China opposing them, the accords are sure to meet diplomatic resistance and their very existence may provoke antagonism in traditional UN forums.

Questions also remain about the impact that the looming US election and the COVID-19 pandemic will have on the program. We already know that President Trump is keen to see astronauts on the moon by 2024. The approach of his Democratic rival, Joe Biden, is a lot less clear. He may well be less wedded to the 2024 deadline and instead aim for broader diplomatic consensus on behavior through engagement at the UN.

While broader international acceptance may be desirable, the US believes that the lure of the opportunities afforded by the Artemis Program will bring other partners on board soon enough. Space-active states now face a stark choice: miss out on being the first to use the resources of the moon, or accept the price of doing business and sign up to the Artemis Accords.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Christopher J. Newman, BA(Hons), PhD is Professor of Space Law and Policy at Northumbria University at Newcastle in the United Kingdom. He is active in the teaching and research of space law and has published extensively on the legal and ethical underpinnings of space governance. Christopher is regularly invited to lecture in universities and at specialist conferences on space law and policy across the UK and internationally.

Christopher graduated from the University of Sussex with a degree in History with English and American Studies. After working in the Metropolitan Police, he studied at Northumbria University for his Postgraduate Diploma in Law (CPE) and his Postgraduate Diploma in Legal Practice (LPC) and secured a training contract in a small high street firm of Solicitors in Hartlepool. Christopher left legal practice in 2004 and joined the University of Sunderland where he obtained his PhD in Cross-Comparative Public Order Law in 2011, becoming Reader in Law in 2013.