Rocky asteroid Ryugu got its rubble from a porous parent, study finds

The rocky object that spawned the asteroid Ryugu may have been extraordinarily porous, a new study finds. The new discovery could shed light on how planets formed in the solar system.

The most common kind of asteroids found in the outer main asteroid belt are carbonaceous or C-type asteroids. Previous research suggested they are relics of the early solar system that hold troves of primordial material from the nebula that gave birth to the sun and its planets. This makes research into C-type asteroids essential when it comes to understanding planetary formation.

However, much remains unknown about the physical properties of C-type asteroids. The carbonaceous chondrite meteoroids that are thought to originate from these asteroids often fail to survive entry into Earth's atmosphere.

Related: Photos of asteroids in deep space

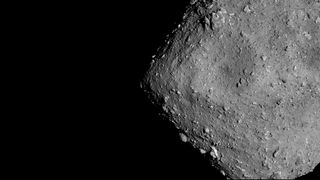

To uncover secrets about C-type asteroids, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) dispatched the spacecraft Hayabusa2 to Ryugu, a 2,790-foot-wide (850 meters) near-Earth asteroid that is one of the darkest celestial bodies in the solar system. The C-type asteroid's name, which means "dragon palace," refers to a magical underwater castle in a Japanese folk tale.

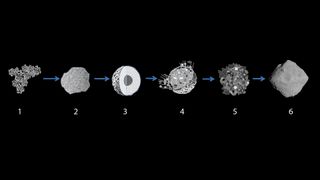

In 2018, Hayabusa2 arrived at Ryugu to map it from orbit and deploy rovers on the boulder-covered asteroid. Scientists found Ryugu was only about half as dense as carbonaceous chondrite meteoroids, which suggested the asteroid was essentially a loosely packed pile of rubble that was porous enough to be about 50% empty space.

To learn more about Ryugu, the researchers thermally imaged the asteroid's surface. Although they had expected its boulders to be denser and therefore colder than their surroundings, they surprisingly found its surface was dominated by boulders that were about the same temperature, suggesting they had a porosity of about 30% to 50%. This was consistent with images from rover pictures that showed that most of the boulders had cauliflower-like, crumbly surfaces.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Even the 100-meter-class boulders were found to be porous and fragile material," study lead author Tatsuaki Okada, a planetary scientist at JAXA's Institute of Space and Astronautical Science in Sagamihara, Japan, told Space.com.

The scientists did see a few dense boulders interspersed among the porous rocks that were about the same density as carbonaceous chondrite meteorites. This leads the researchers to suspect that when meteoroids from C-type asteroids fall to Earth, the crumbly rock that makes up most of these asteroids disintegrates upon entry, with only the denser material surviving, Okada said.

These findings suggest that Ryugu was a rubble pile formed from the fragments of a shattered parent body that was 30% to 50% porous. The few dense boulders seen on Ryugu might have come from the innermost core of this parent body, where the weight of the asteroid would have compressed the spongy rock into something denser, or they might be surviving fragments of meteorite impacts, Okada said.

"People who live on Earth consider stone a dense and consolidated material, but for a small body, a world of low gravity, a stone is not consolidated and is porous material, because it has never experienced the pressurized conditions like in the Earth's interior," Okada said.

All in all, the researchers suggested that C-type asteroids might have formed from fluffy dust or pebbles in the early solar system. The fluffy nature of these asteroids might have strongly influenced planetary formation — for example, the greater ease with which these rocks could crumble might mean that impacts against them were less likely to throw off fragments with great force to shatter other asteroids, they said.

The scientists detailed their findings online March 16 in the journal Nature.

- Diamond asteroids: How Bennu and Ryugu got their fancy shapes

- There's something weird about the craters of asteroid Ryugu

- How did the solar system form?

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us

Most Popular