Chinese smartphone camera photographs Earth from space

The project is primarily a marketing effort, but it could have practical applications as well.

Chinese electronics firm Xiaomi went above and beyond to advertise its latest smartphone, sending the device's 100-megapixel camera into space.

The camera, which is based on the 108-megapixel Xiaomi M10 Pro quad camera, was integrated into a cubesat that launched in November 2019.

Xiaomi used the quite brilliant orbital imagery for the Chinese launch of its new Mi 10 smartphones on Feb.13.

Related: Latest news about China's space program

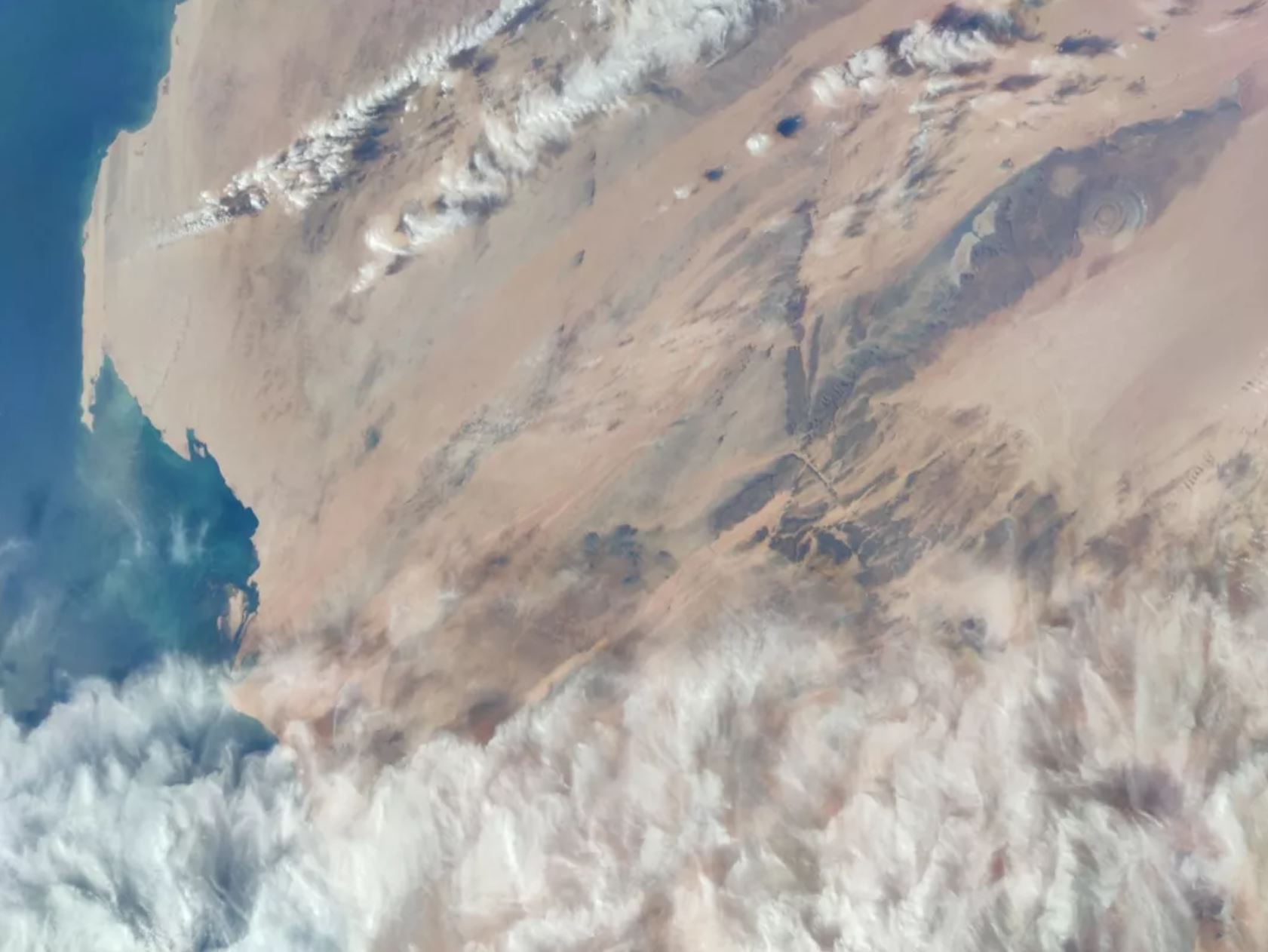

The Xiaomi images show Earth from an altitude of around 307 miles (495 kilometers), where the Chinese-made cubesat travels at close to 17,450 mph (28,080 km/h).

Visible in one image is the Richat Structure, also known as the "Eye of Africa" and "Eye of the Sahara."

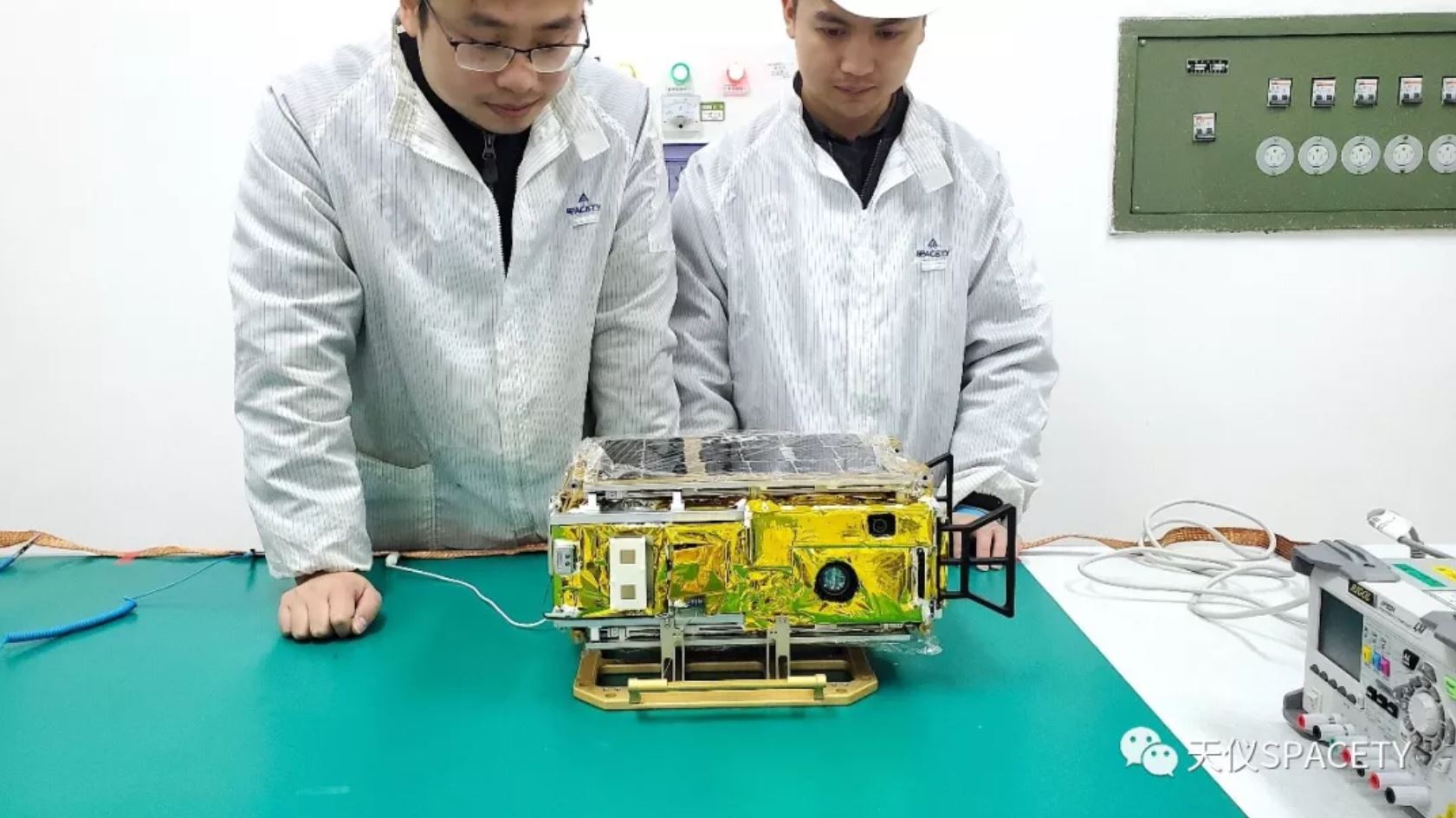

Spacety, a Changsha-based private company that provides end-to-end small satellite services, integrated the camera into one of its cubesats, which launched in November.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The teams from Spacety and Xiaomi together solved 343 problems over a period of 168 days to get the 108-megapixel camera ready for launch aboard the Xiaoxiang 1-08, or "Dianfeng," cubesat.

Digital photography has its roots in outer space. Eugene Lally, an engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, was the first to develop the concept of the digital camera. A JPL team led by Eric Fossum later developed a complementary metal-oxide semiconductor active-pixel sensor (CMOS-APS) for imaging in space and on Earth.

While the Xiaomi orbital exercise was part of an advertising campaign, there are practical uses for such projects. Spacety has been looking at ways to lower the cost of space missions, testing both industrial and consumer-grade instruments and devices for use in space. And using cubesats with small payloads can bring big results at low cost.

For example, the United States' LandSat 8 satellite, which launched in 2013, weighed 5,782 lbs. (2,623 kilograms) and returns images with a resolution of 98 feet (30 meters) per pixel from an altitude of 438 miles (705 km). Landsat 8 had a price tag of $855 million.

Xiaoxiang-1-08 was manufactured and launched within 2019, with a mass of a few pounds. The Mi 10 camera returned images at a resolution of 197 feet (60 m) per pixel. Of course, Landsat 8 is far more capable, working for many years and observing Earth with its Operational Land Imager in nine spectral bands, compared with the three (red, green, blue) of the Mi 10.

Xiaoxiang 1-08 also carries other experimental payloads. These include a laser communications payload for Chinese firm Laserfleet and tiny, cutting-edge solid iodine thrusters for French startup Thrustme.

The cubesat rode to orbit aboard a Chinese Long March 4B rocket, whose primary payload was the Gaofen-7 optical Earth observation satellite. The rocket also tested grid fins like those designed by SpaceX for guiding the landing of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy first stages.

Following this success, Xiaomi and Spacety are exploring the potential of cooperation in space imaging. This collaboration could have uses in meteorological observation, environmental warning, marine science and even financial analysis, representatives of the companies have said.

- Cubesats: tiny, versatile spacecraft explained (infographic)

- Photos: amazing images of Earth from space

- China prepares to launch new rockets as part of push to boost space program

Follow Andrew Jones at @AJ_FI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.