How long is a day on Venus? It's always changing, new study reveals

There's a reason scientists haven't been able to get their measurements to line up.

Astronomers have long struggled to pin down how long a day lasts on Venus, but new research suggests the difficulty stems not from flawed measurements but from real variations in the planet's spin.

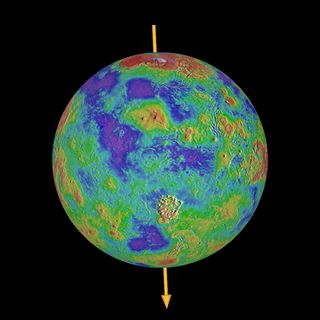

In a new study, scientists used a massive radar system to bounce lightwaves off our neighboring planet over the course of more than a decade. As a result, the researchers were able to measure how tilted Venus' axis is, how big its core is, and how long it takes the planet to complete one full rotation.

"Venus is our sister planet, and yet these fundamental properties have remained unknown," Jean-Luc Margot, a planetary scientist at the University of California Los Angeles and lead author of the new research, said in a statement.

Related: Photos of Venus, the mysterious planet next door

To crack these continuing mysteries, Margot and his colleagues turned to two powerful radar facilities: NASA's Goldstone antenna in California and the massive main dish of the Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia.

Between 2006 and 2020, the team used this radar system to bounce a beam from Goldstone to Venus. The researchers then studied the signals that returned to both sites on Earth, comparing the time between when each facility caught the echo, about 20 seconds apart.

In the statement, Margot compared the technique to shining a light at a mirrorball. "We use Venus as a giant disco ball," he said. "We illuminate it with an extremely powerful flashlight — about 100,000 times brighter than your typical flashlight. And if we track the reflections from the disco ball, we can infer properties about the spin."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

All told, the researchers used the system to gaze at Venus a total of 121 times. Because the technique is so finicky, requiring both facilities to be in perfect shape, the researchers were able to gather useful data with just 21 of those attempts.

"We found that it's actually challenging to get everything to work just right in a 30-second period," Margot said. "Most of the time, we get some data. But it's unusual that we get all the data that we're hoping to get."

But by analyzing those precious observations, the scientists were able to calculate the precise tilt of Venus' spin (2.6392 degrees, much smaller than Earth's 23-degree tilt). The analyses also estimate the size of Venus' core to be about 4,350 miles (7,000 kilometers) across, or 58% of the planet's diameter, although the scientists emphasize that calculation is quite uncertain.

The day-length calculations, on the other hand, the scientists were able to measure quite precisely, and the team's results explain why previous analyses haven't matched each other. A day on Venus, the researchers determined, lasts an average of 243.0226 Earth days — but from one Venusian day to another, the time needed for the planet to make one complete spin can vary by up to 20 minutes.

"That probably explains why previous estimates didn't agree with one another," Margot said.

The researchers think the variation is caused by the pull of Venus' thick, fast-moving atmosphere. Earth's atmosphere affects our planet's spin, but because it's much less substantial than the Venusian clouds, the difference in days is on the scale of milliseconds. The much heftier Venusian atmosphere takes just four days to circle the slowly spinning planet in a phenomenon scientists don't quite understand but that could impact the planet's spin.

But if humans ever want to send more missions to Venus, we'll need to sort this out since, without it, spacecraft could land as far as 19 miles (30 km) away from where mission scientists intend.

"Without these measurements," Margot said, "we're essentially flying blind."

The research is described in a paper published April 29 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.