Weird nearby gamma-ray burst defies expectations

This isn't how GRBs are supposed to behave.

A team of scientists has gotten their best look yet at a gamma-ray burst, the most dramatic type of explosion in the universe.

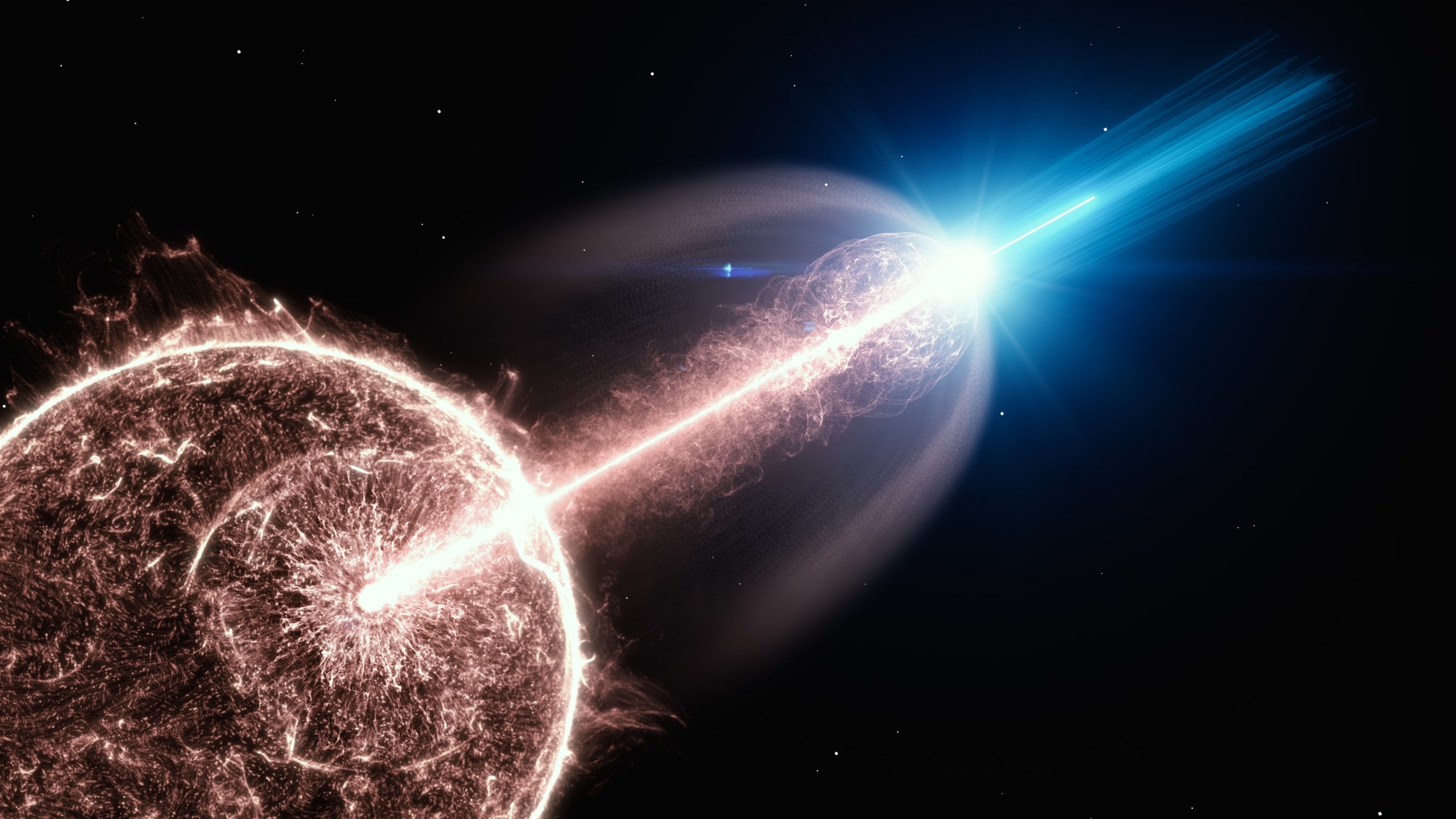

Astronomers think some of these explosions occur when a massive star — five or 10 times the mass of our sun — detonates, abruptly becoming a black hole. Gamma-ray bursts may also occur when two superdense stellar corpses called neutron stars collide, often forming a black hole. And conveniently, a gamma-ray burst that scientists watched during a few nights in 2019 likely occurred only about 1 billion light-years away from Earth, relatively close by for these dramatic events.

"We were really sitting in the front row when this gamma-ray burst happened," Andrew Taylor, a physicist at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (German Electron Synchrotron, or DESY) and co-author on the new paper, said in a statement. "We could observe the afterglow for several days and to unprecedented gamma-ray energies."

Related: Record breaking gamma-ray burst captured by Fermi

Two NASA space-based observatories, Fermi and Swift, first detected the event, which is known as GRB 190829A because it was detected on Aug. 29, 2019. The fireworks came from the direction of the constellation Eridanus, a large swath of sky in the Southern Hemisphere.

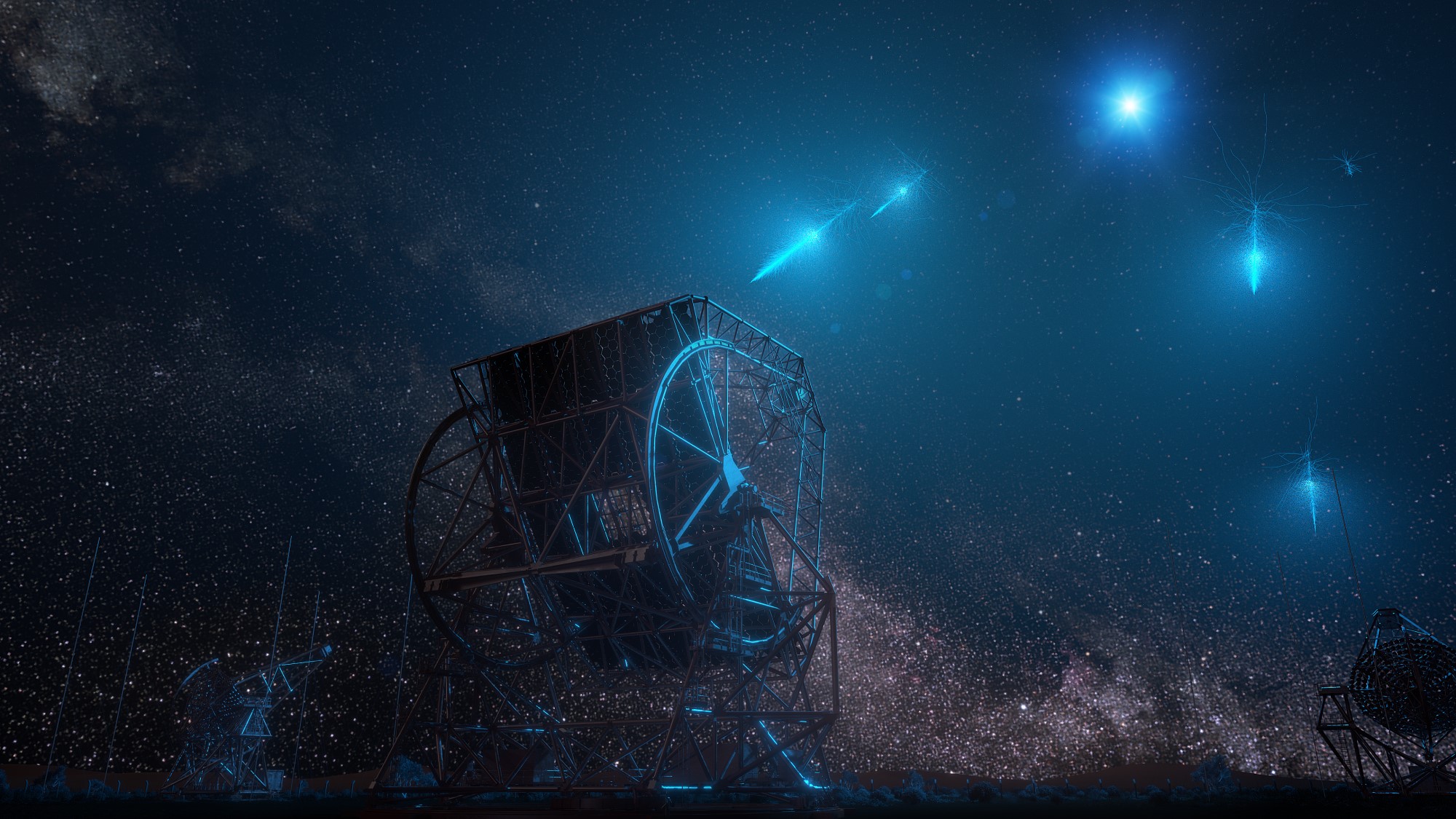

When the scientists behind the new research heard about the gamma-ray burst detection, they mobilized a set of five gamma-ray telescopes in Namibia, called the High Energy Stereoscopic System (HESS). Over three nights, the telescopes observed the explosion for a total of 13 hours, in an attempt to understand what took place.

With those observations, the scientists could analyze much higher-energy photons than is possible in more distant gamma-ray bursts.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This is what's so exceptional about this gamma-ray burst," Edna Ruiz-Velasco, an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg and co-author on the new research, said in the same statement. "It happened in our cosmic backyard, where the very-high-energy photons were not absorbed in collisions with background light on their way to Earth, as happens over larger distances in the cosmos."

During those analyses, the team noticed that the patterns of X-rays and very high-energy gamma-rays matched — something scientists wouldn't expect, since they believe different phenomena cause the two different types of radiation.

But so far, scientists have only observed four of these bright explosions from the surface of Earth, so they're hoping that new instruments and additional observations give them more insight into the details of gamma-ray bursts.

The research is described in a paper published June 3 in the journal Science.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.