Ancient Earth had a thick, toxic atmosphere like Venus — until it cooled off and became liveable

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Antony Burnham, Research Fellow, Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University

Hugh O'Neill, Professor, Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University

Earth is the only planet we know contains life. Is our planet special? Scientists over the years have mulled over what factors are essential for, or beneficial to, life. The answers will help us identify other potentially inhabited planets elsewhere in the galaxy.

To understand what conditions were like in Earth’s early years, our research tried to recreate the chemical balance of the boiling magma ocean that covered the planet billions of years ago, and conducted experiments to see what kind of atmosphere it would have produced. Working with colleagues in France and the United States, we found Earth’s first atmosphere was likely a thick, inhospitable soup of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, much like what we see on Venus today.

Read more: If there is life on Venus, how could it have got there? Origin of life experts explain

How Earth got its first atmosphere

A rocky planet like Earth is born through a process called “accretion”, in which initially small particles clump together under the pull of gravity to form larger and larger bodies. The smaller bodies, called “planetesimals”, look like asteroids, and the next size up are “planetary embryos”. There may have been many planetary embryos in the early Solar System, but the only one that still survives is Mars, which is not a fully fledged planet like Earth or Venus.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The late stages of accretion involve giant impacts that release enormous amounts of energy. We think the last impact in Earth’s accretion involved a Mars-sized embryo hitting the growing Earth, spinning off our Moon, and melting most or all of what was left.

The impact would have left Earth covered in a global sea of molten rock called a “magma ocean”. The magma ocean would have leaked hydrogen, carbon, oxygen and nitrogen gases, to form Earth’s first atmosphere.

What the first atmosphere was like

We wanted to know exactly what kind of atmosphere this would have been, and how it would have changed as it, and the magma ocean beneath, cooled down. The crucial thing to understand is what was happening with the element oxygen, because it controls how the other elements combine.

If there was little oxygen around, the atmosphere would have been rich in hydrogen (H₂), ammonia (NH₃) and carbon monoxide (CO) gases. With abundant oxygen, it would have been made of a much friendlier mix of gases: carbon dioxide (CO₂), water vapour (H₂O) and molecular nitrogen (N₂).

Read more: The rise and fall of oxygen

So we needed to work out the chemistry of oxygen in the magma ocean. The key was to determine how much oxygen was chemically bonded to the element iron. If there’s a lot of oxygen, it bonds to iron in a 3:2 ratio, but if there is less oxygen we see a 1:1 ratio. The actual ratio may vary between these extremes.

When the magma ocean eventually cooled down, it became Earth’s mantle (the layer of rock beneath the planet’s crust). So we made the assumption that the oxygen-iron bonding ratios in the magma ocean would have been the same as they are in the mantle today.

We have plenty of samples of the mantle, some brought to the surface by volcanic eruptions and others by tectonic processes. From these, we could work out how to put together a matching mix of chemicals in the laboratory.

In the lab

We determined this atmosphere was composed of CO₂ and H₂O. Nitrogen would have been in its elemental form (N₂) rather than the toxic gas ammonia (NH₃).

But what would have happened when the magma ocean cooled down? It seems the early Earth cooled enough for the water vapour to condense out of the atmosphere, forming oceans of liquid water like we see today. This would have left an atmosphere with 97% CO₂ and 3% N₂, at a total pressure roughly 70 times today’s atmospheric pressure. Talk about a greenhouse effect! But the Sun was less than three-quarters as bright then as it is now.

How Earth avoided the fate of Venus

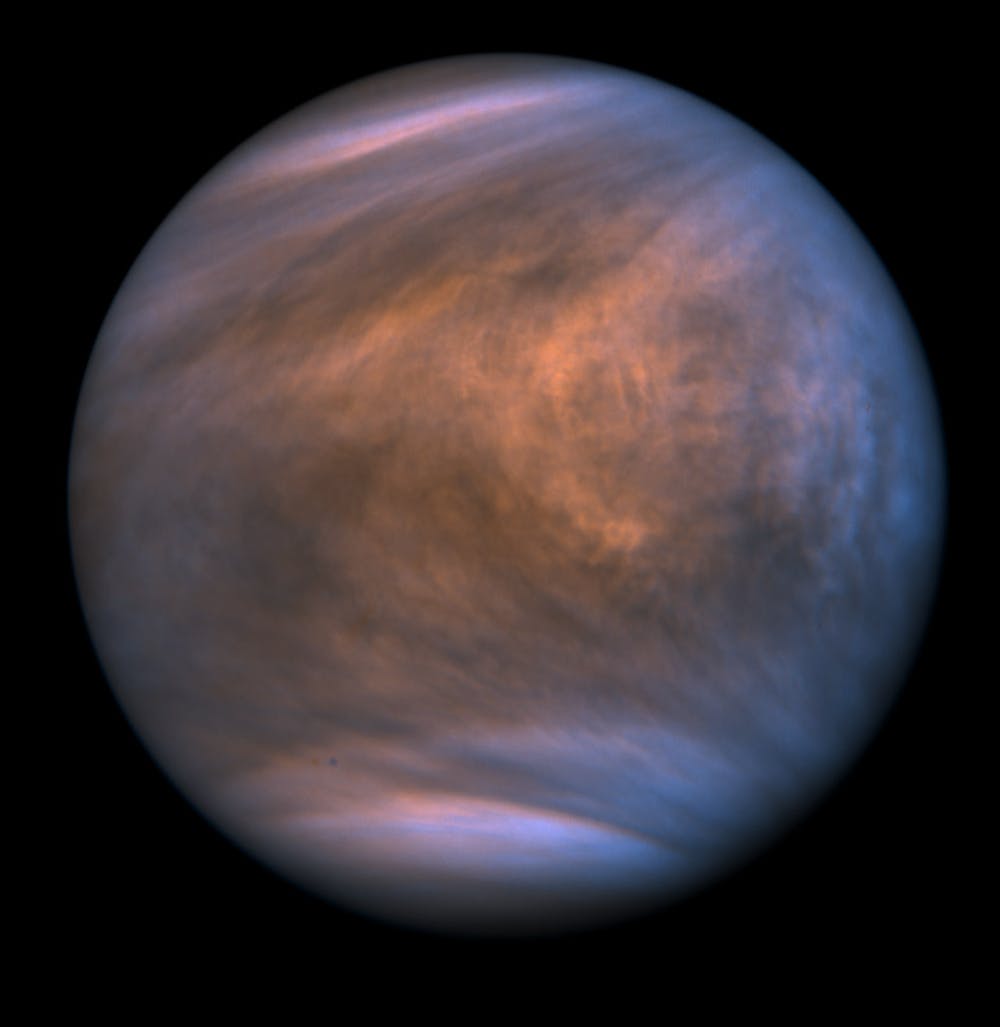

This ratio of CO₂ to N₂ is strikingly like the present atmosphere on Venus. So why did Venus, but not Earth, retain the hellishly hot and toxic environment we observe today?

The answer is that Venus was too close to the Sun. It simply never cooled down enough to form water oceans. Instead, the H₂O in the atmosphere stayed as water vapour and was slowly but inexorably lost to space.

On the early Earth, the water oceans instead slowly but steadily drew down CO₂ from the atmosphere by reaction with rock – a reaction known to science for the past 70 years as the “Urey reaction”, after the Nobel prizewinner who discovered it – and reducing atmospheric pressure to what we observe today.

So, although both planets started out almost identically, it is their different distances from the Sun that put them on divergent paths. Earth became more conducive to life while Venus became increasingly inhospitable.

Read more: Ancient minerals on Earth can help explain the early solar system

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

I am interested in trace element partitioning (particularly in relation to melt structure and crystal chemistry) and diamond petrogenesis.

My PhD, entitled "Zircon as a recorder of the oxygen fugacity of magmas" was carried out at Imperial College London from 2008 - 2012 under the supervision of Andrew Berry. From 2012 - 2014 I worked at the University of Bristol, studying the origin of super-deep diamonds from the Juina region, Brazil. At RSES I work with Hugh O'Neill, examining the mechanisms of trace element substitution into a range of minerals.