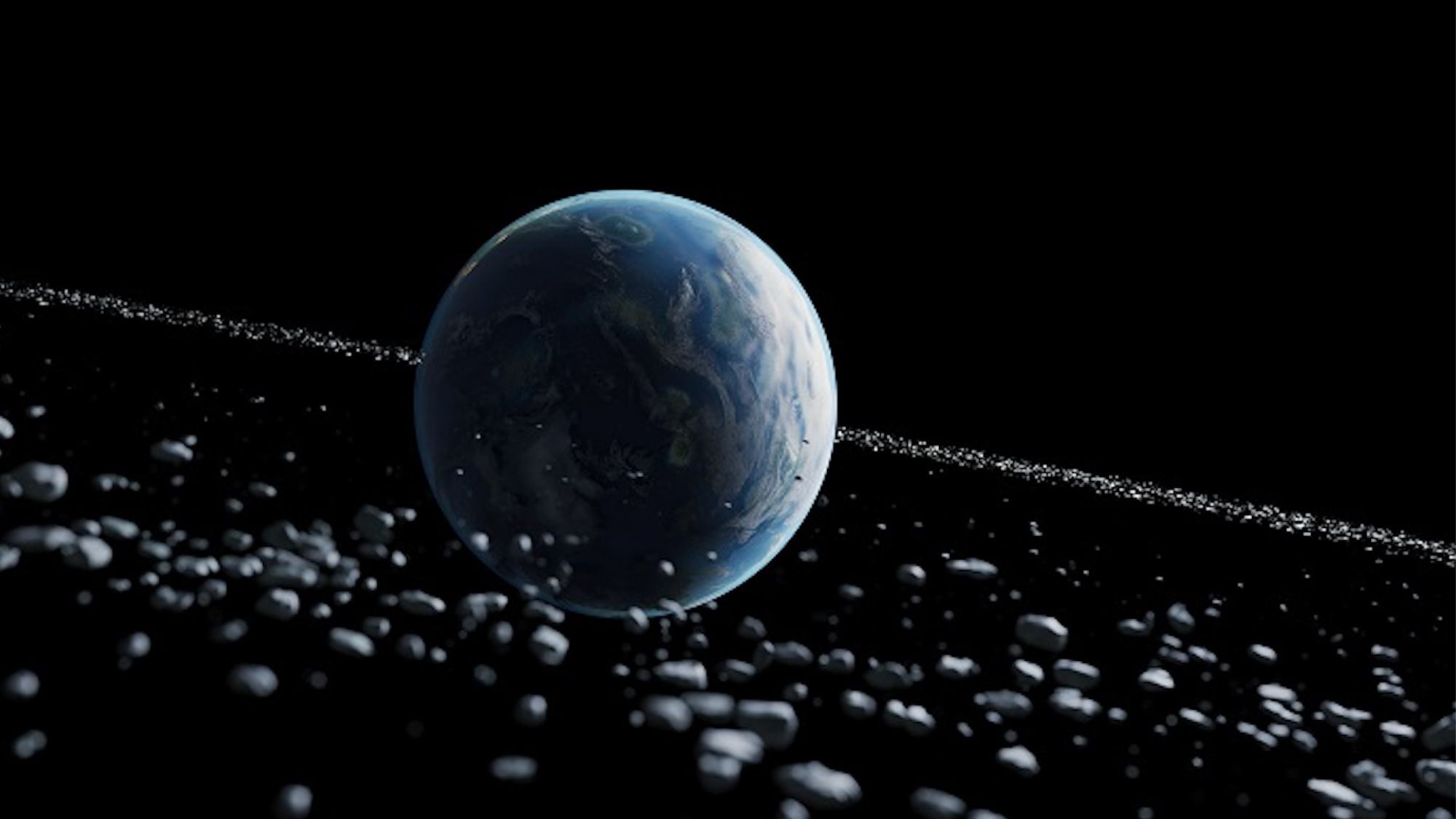

Earth had Saturn-like rings 466 million years ago, new study suggests

The temporary structure likely consisted of debris from a broken-up asteroid.

Earth may have sported a Saturn-like ring system 466 million years ago, after it captured and wrecked a passing asteroid, a new study suggests.

The debris ring, which likely lasted tens of millions of years, may have led to global cooling and even contributed to the coldest period on Earth in the past 500 million years.

That's according to a fresh analysis of 21 crater sites around the world that researchers suspect were all created by falling debris from a large asteroid between 488 million and 443 million years ago, an era in Earth's history known as the Ordovician during which our planet witnessed dramatically increased asteroid impacts.

A team led by Andy Tomkins, a professor of planetary science at Monash University in Australia, used computer models of how our planet's tectonic plates moved in the past to map out where the craters were when they first formed over 400 million years ago. The team found that all the craters had formed on continents that floated within 30 degrees of the equator, suggesting they were created by the falling debris of a single large asteroid that broke up after a near-miss with Earth.

Related: Planet Earth: Everything you need to know

"Under normal circumstances, asteroids hitting Earth can hit at any latitude, at random, as we see in craters on the moon, Mars and Mercury," Tomkins wrote in The Conversation. "So it's extremely unlikely that all 21 craters from this period would form close to the equator if they were unrelated to one another."

The chain of crater locations all hugging the equator are consistent with a debris ring orbiting Earth, scientists say. That's because such rings typically form above planets' equators, as occurs with those circling Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune. The chances that these impact sites were created by unrelated, random asteroid strikes is about 1 in 25 million, the new study found.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers estimate that the ring-spawning asteroid would be about 7.7 miles (12.5 kilometers) wide if it were a "rubble pile," or slightly smaller if it were a solid body. Once it shattered after nearing Earth's vicinity, its fragments would have "jostled around" before settling into a debris ring orbiting Earth's equator, Tomkins said.

"Over millions of years, material from this ring gradually fell to Earth, creating the spike in meteorite impacts observed in the geological record," Tomkins added in a university statement. "We also see that layers in sedimentary rocks from this period contain extraordinary amounts of meteorite debris."

The team found that this debris, which represented a specific type of meteorite and was found to be abundant in limestone deposits across Europe, Russia and China, had been exposed to a lot less space radiation than meteorites that fall today. Those deposits also reveal signatures of multiple tsunamis during the Ordovician period, all of which can be best explained by a large, passing asteroid capture-and-break-up scenario, the researchers argue.

The new study is a "new and creative idea that explains some observations," Birger Schmitz of Lund University in Sweden told New Scientist. "But the data are not yet sufficient to say that the Earth indeed had rings."

Searching for a common signature in specific asteroids grains across the newly studied impact craters would help test the hypothesis, Schmitz added.

If Earth did sport a Saturn-like ring around its equator, the ring would have significantly affected our planet's climate, according to the new study. Because Earth's axis is tilted relative to its orbit around the sun, the ring would have cast a shadow over parts of our planet's surface that may have caused global cooling. But the specifics are still murky, the researchers say.

The researchers speculate that such an event may have contributed to the dramatic cooling of our planet 465 million years ago, which led to the coldest period in the past half a billion years, known as the Hirnantian Ice Age.

"We don't know how the ring would have looked from Earth or how much light it would have cut out or how much debris there would have had to be in the ring to lower the temperature on Earth," Tomkins told New Scientist.

This research is described in a paper published Monday (Sept. 16) in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.