Ancient Mars was warm and wet only intermittently, a new study suggests.

Although the Martian surface is bone-dry today, it's clear that liquid water flowed across it billions of years ago. The planet is scored by river channels, and ancient lakebeds lurk on the floors of multiple craters — including Gale and Jezero, which are currently being explored by NASA's Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, respectively.

But it remains unclear, and a topic of considerable scientific debate, what ancient Mars was really like. Was the planet warm and wet continuously long ago, or has it pretty much always been frosty, with only sporadic balmy stretches allowing transient water flows?

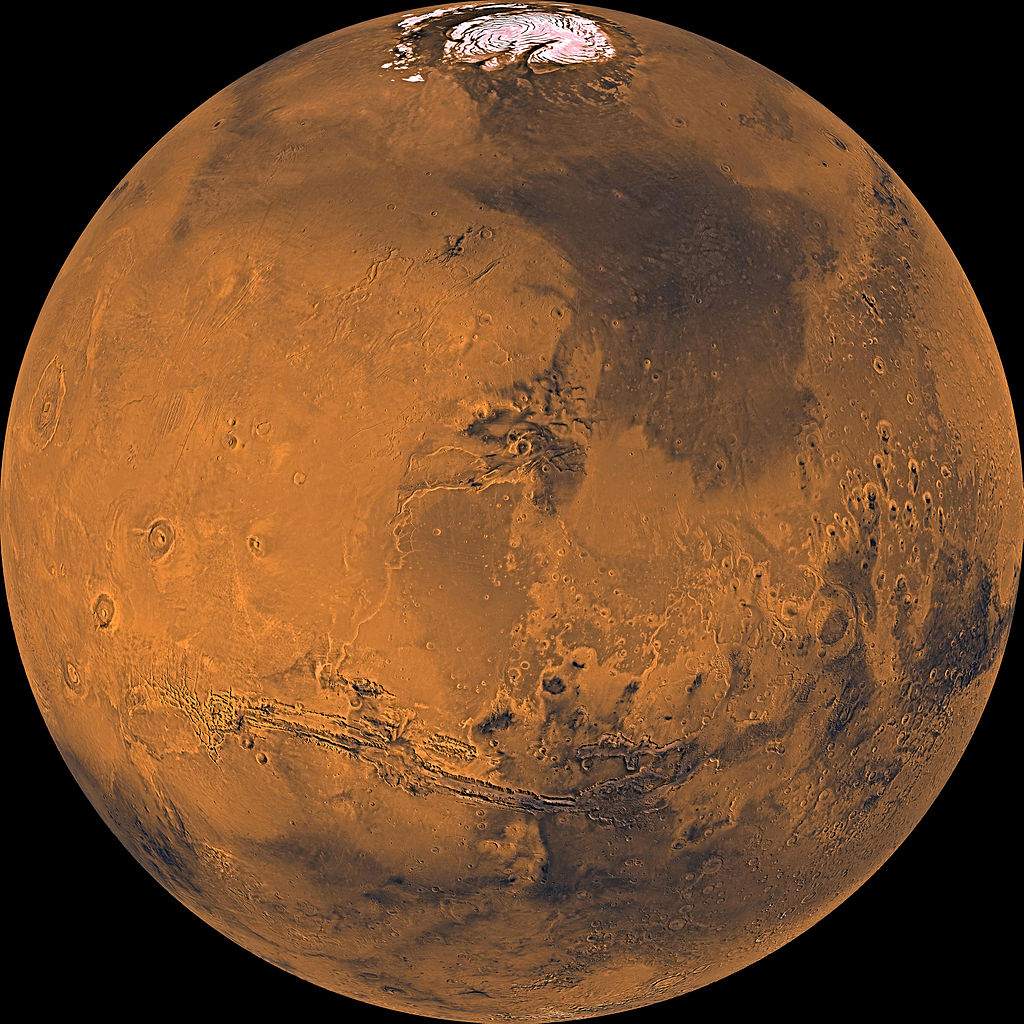

The search for life on Mars: A photo time line

A new study bolsters the latter view, suggesting that it took dramatic events to warm Mars' cold heart, and that such ancient deviations never lasted long.

“Mars was intermittently warmed when its atmospheric composition was altered by the input of gases derived from volcanism and meteorite impactors," co-author Joel Hurowitz, a geoscientist at Stony Brook University in New York, said in a statement.

These warm spells "allowed water to flow across the surface, forming rivers and lakes and the rocks and minerals we associate with water on Mars,” Hurowitz said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new study, led by Robin Wordsworth of Harvard University, presents a novel climate model of ancient Mars. The model takes into account a variety of factors, including the effects of volcanic eruptions, which poured greenhouse gases into the Martian air, and the escape of hydrogen from the atmosphere into space.

That hydrogen escape, driven by the solar wind, ramped up dramatically after Mars lost its protective global magnetic field. By about 3.7 billion years ago, the once-thick Martian atmosphere was just 1% as dense as that of present-day Earth, and the era of rivers and lakes on the Red Planet's surface was coming to an end.

The new study, which was published online today (March 8) in the journal Nature Geoscience, helps flesh out that era and the Red Planet's life-hosting potential. For example, it suggests that "wet" Mars was still very cold, with average annual surface temperatures below minus 28 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 33 degrees Celsius).

"The dynamic history of Martian environments proposed here suggests opportunities for the emergence of life during warm, wet intervals when reducing conditions would have favored prebiotic chemistry, but also challenges for the persistence of surface life in the face of frequent and, through time, lengthening intervals of mainly cold and dry oxidizing environments," Wordsworth and his colleagues wrote in the new study.

"Reducing conditions" refers to an atmosphere in which oxidation — the stripping of electrons from atoms and molecules — is prevented or minimized. By contrast, oxidation is prevalent in "oxidizing environments."

Oxygen is a commonly proposed biosignature — a possible sign of life for which to search in the atmospheres of alien planets. Interestingly, the new model predicts that Mars had an oxygen-rich atmosphere for long stretches "in the middle period of its history without requiring the presence of life, indicating that O2 detection alone can be a 'false positive' for life in some circumstances," the researchers wrote in the new study.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.