Astronomers spot ancient effects from a supermassive black hole's jets

It all went down 11 billion light-years away.

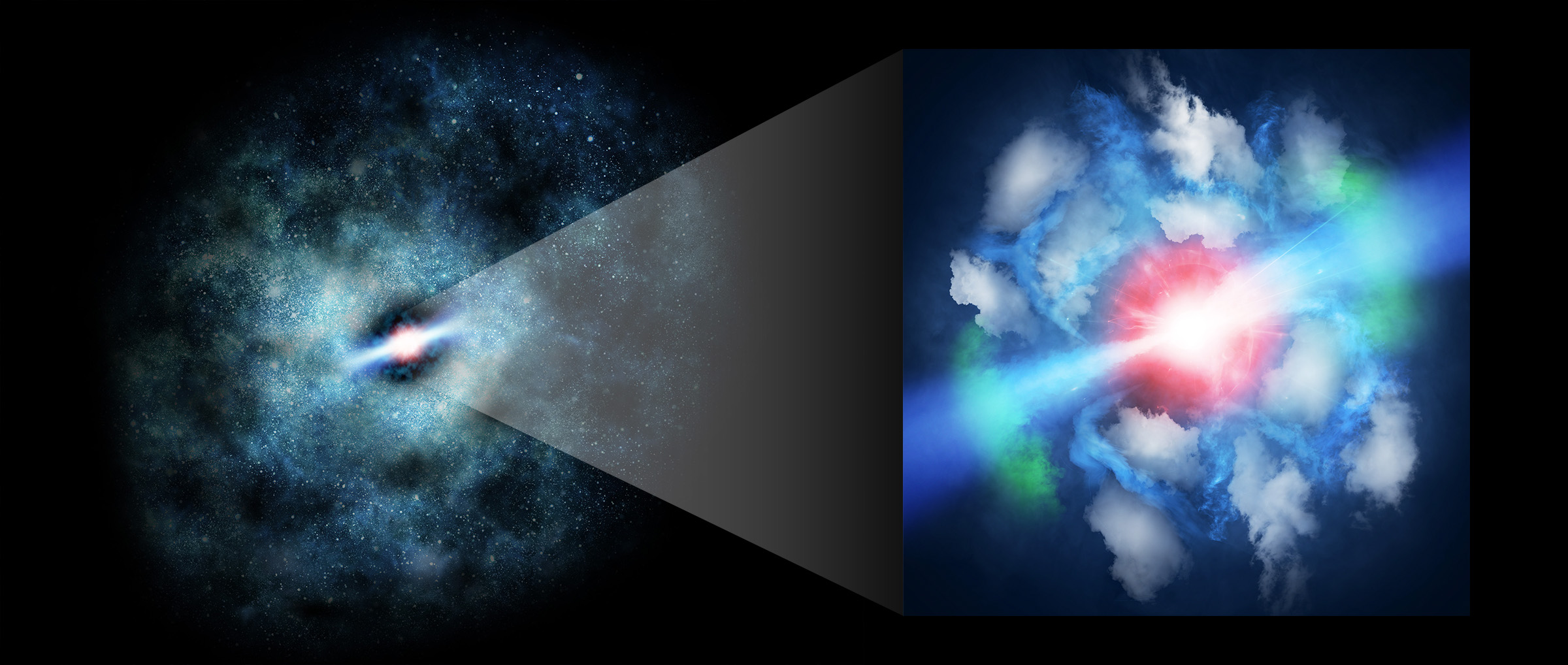

Astronomers have gleaned their first insight to what the jets blasting off of supermassive black holes may have done to surrounding gas in the young universe.

Scientists are curious about this interaction around a black hole because they believe the phenomenon may slow star formation in the region. And while astronomers have studied such interactions in nearby areas of the universe, they have struggled to do so at great distances. Those distances allow them to see into the past, since the longer light has to travel to reach Earth, the earlier in the universe it illuminates. But now, a team of astronomers believes they have accomplished that feat in their study of an object called MG J0414+0534.

"We are perhaps witnessing the very early phase of jet evolution in the galaxy," Satoki Matsushita, a research fellow at Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan and a co-author on the new research, said in a statement. "It could be as early as several tens of thousands of years after the launch of the jets."

Related: No escape: Dive into a black hole (infographic)

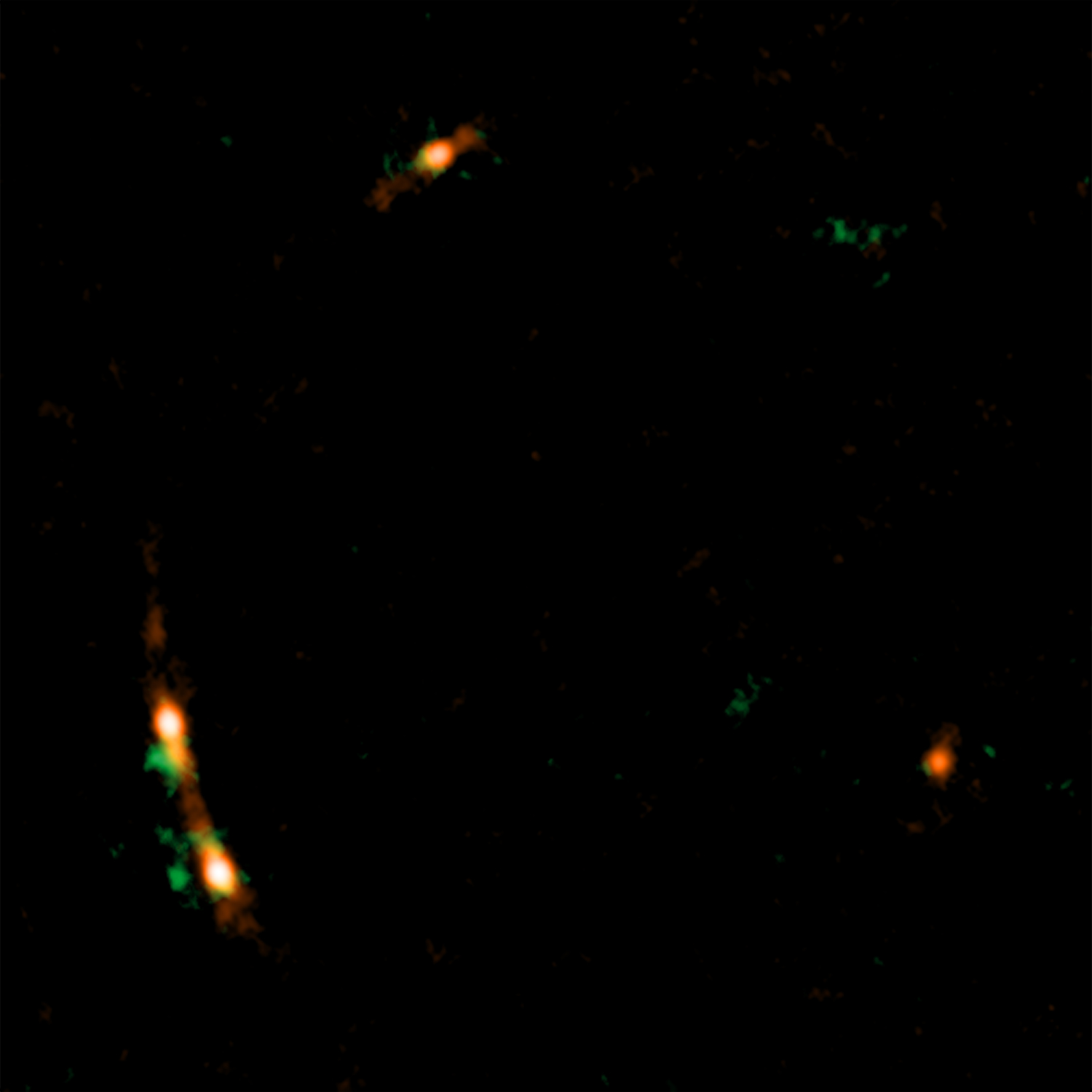

That freshness reflects the fact that the object is 11 billion light-years away from Earth. The only reason astronomers could spot it at all is that a massive galaxy happened to align between the scientists and their target. The intervening object acted as a gravitational lens, magnifying the mystery on the other side of it.

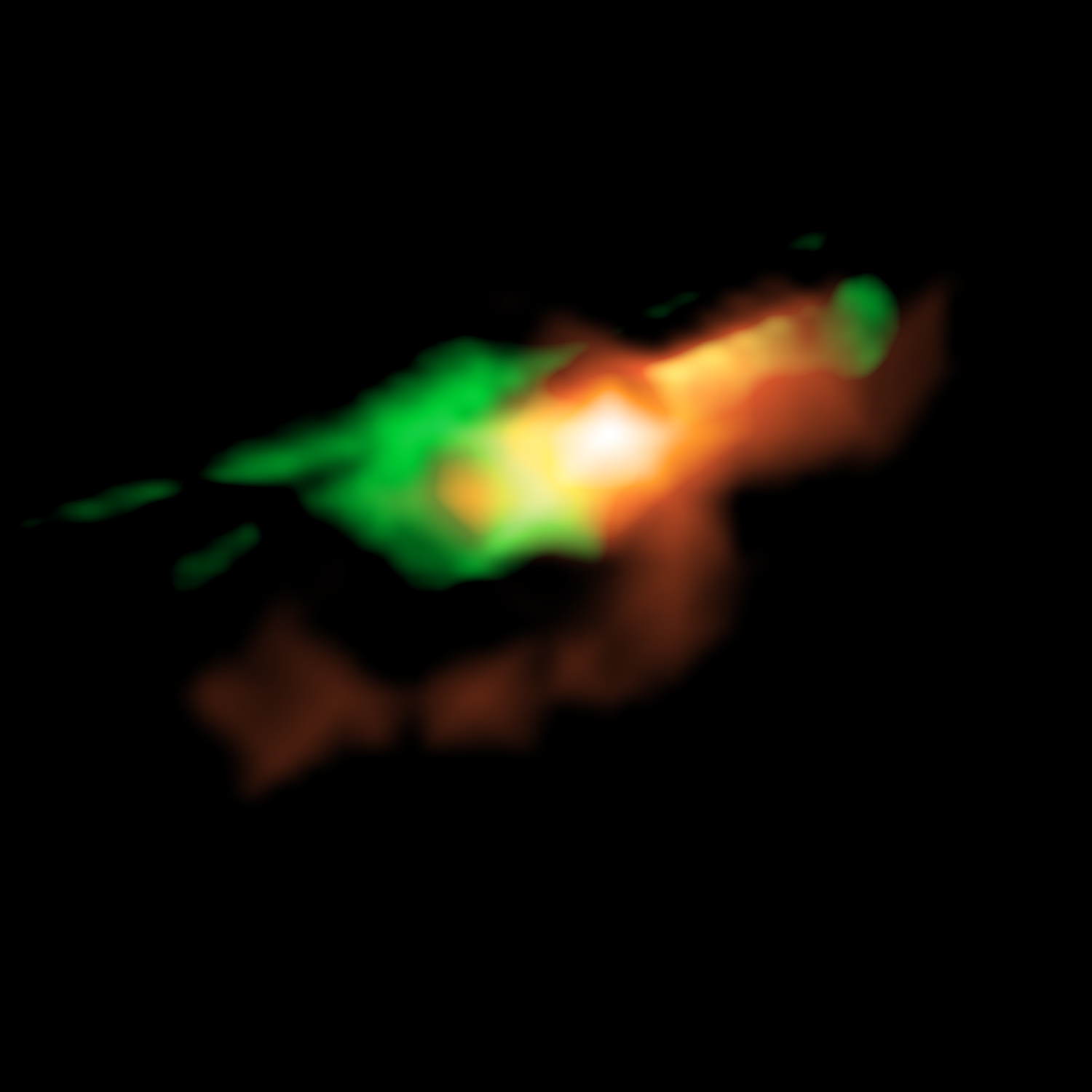

That mystery was a quasar. Although black holes are known for consuming all in their path, that isn't strictly true, and in the case of quasars, jets shoot out of the black hole's top and bottom, filled with particles that are instead accelerated to nearly the speed of light as they flee the black hole.

Between the gravitational lensing and the power of the array the scientists used to study MG J0414+0534, the quasar appeared 9,000 times larger in their data than it would to the unaided eye, according to the statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That detail allowed the scientists to determine that the jets are indeed shaping the gas around them, whipping the clouds of gas to speeds as fast as 373 miles per second (600 kilometers per second).

"We found telltale evidence of significant interaction between jets and gaseous clouds even in the very early evolutionary phase of jets," lead author Kaiki Inoue, a cosmologist at Kindai University, Japan, said in the same statement. "I think that our discovery will pave the way for a better understanding of the evolutionary process of galaxies in the early universe."

The research is described in a paper published March 27 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

- Why are black holes so weird? 'Ask a Spaceman' explains in new episode

- All your questions about the new black hole image answered

- Weird black hole physics revealed in NASA visualization

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.