Celebrating the animal astronauts who paved the way for human spaceflight

From insects to primates, from dogs and cats to cold-blooded reptiles, animals have played a significant role in space exploration since the first fruit flies launched to Earth's upper atmosphere in 1947.

Animals were the earliest precursor to the human spaceflight program. International space agencies relied on a variety of animals to test the survivability of spaceflight, as well as the effects microgravity might have on human's biological processes.

Soon after launching fruit flies, American researchers flew monkeys and mice on suborbital flights between 1948 and 1951. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union launched dozens of stray dogs on suborbital flights throughout the 1950s — all before Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to journey into outer space on April 12, 1961.

Related: A history of animals in space (infographic)

Buy "Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space" (Harper, 2021) by Stephen Walker on Amazon.com.

The hardcover is $25.49, a Kindle version is available for $14.99 and the audiobook is $23.49.

Space.com sat down with Stephen Walker, author of "Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space" (Harper, 2021), to discuss the important role animals have had in paving the way for human spaceflight and how it all started nearly 75 years ago. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. You can find the book on Amazon.

Space.com: What are some of the space-faring animals you've covered in your research?

Stephen Walker: Thousands of animals have been in space. As far as I can tell from my research, the different animals — and the variety is staggering — include, in no particular order, dogs, cats, monkeys, chimpanzees, fruit flies, cockroaches, jellyfish, frogs, moths, spiders, crickets, tortoises, worms, honey bees, mice, rats, snails, ants, squid and, of course, guinea pigs.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And there's one particular animal that I absolutely love, which is the tardigrade. Sometimes called water bears, they are these tiny, sweet-looking things that can survive absolutely anywhere. In 2007, a European Space Agency mission put 3,000 tardigrades outside of a rocket, fully exposing the animals to all the hazards of space — radiation, no oxygen, extremely cold temperatures. They weren't protected by anything and some 68% of them survived for 12 days. I mean, it's incredible, actually.

Some other examples include frogs, which were sent to space for balance research in weightlessness. Honey bees were sent up to understand if and how they construct a hive or make honey in space — and they did. The Soviets sent two tortoises around the moon in 1968, shortly before Apollo 8. In 2011, two spiders — Esmeralda and Gladys — were studied on the International Space Station and were able to adapt to weightless conditions and created quite weirdly beautiful space webs to catch flies to survive.

So, an enormous variety of animals have gone to space. It all started with fruit flies in 1947 and continues to this day in 2021, with baby squid being the most recently launched in June, aboard a Dragon cargo capsule as part of a SpaceX resupply mission to the International Space Station.

Space.com: Why do you think animals were first sent up to space?

Walker: In 1947, the cold war had begun and, at this point, it was becoming very obvious that the next frontier is space. And, frankly, the next battle ground between the Soviet Union and the United States. However, there were a lot of things that they just did not know about space or how the human body would respond to the kind of velocity needed to achieve Earth orbit.

So, in order to find out, what they had to do was send up animals — starting with some fruit flies in 1947, which the U.S. launched some 40 miles into the upper atmosphere on a V2 rocket. Then, they moved on to monkeys. In 1948, they started Project Albert — a seminal moment in the history of space flight. The project consisted of six separate flights, each of which had a rhesus monkey inside the nose cone of a V2 rocket. Every single one of those monkeys were killed.

Space.com: How were different animals selected for spaceflight experiments back then?

Walker: As I say in my book "Beyond," the choice of animal to experiment with reflects the ideological culture of that society. When the Russians began sending animals to space in 1951, they started with dogs because they are obedient and easy to train — they were essentially meant to endure the mission, much like cosmonauts.

Americans chose chimpanzees, partly because of their obvious similarities to humans. American astronauts would have more control over their spacecraft than Soviet cosmonauts and so certainly the chimpanzees were given tasks which involved a certain amount of autonomous action, pulling levers and so on, to verify that humans would be able to do this in space, too.

You could say the Soviets were all about obedience and the Americans more about autonomy and independent action, rather like their respective ideologies.

Space.com: How did the Soviet Union select the dogs that they sent up to space?

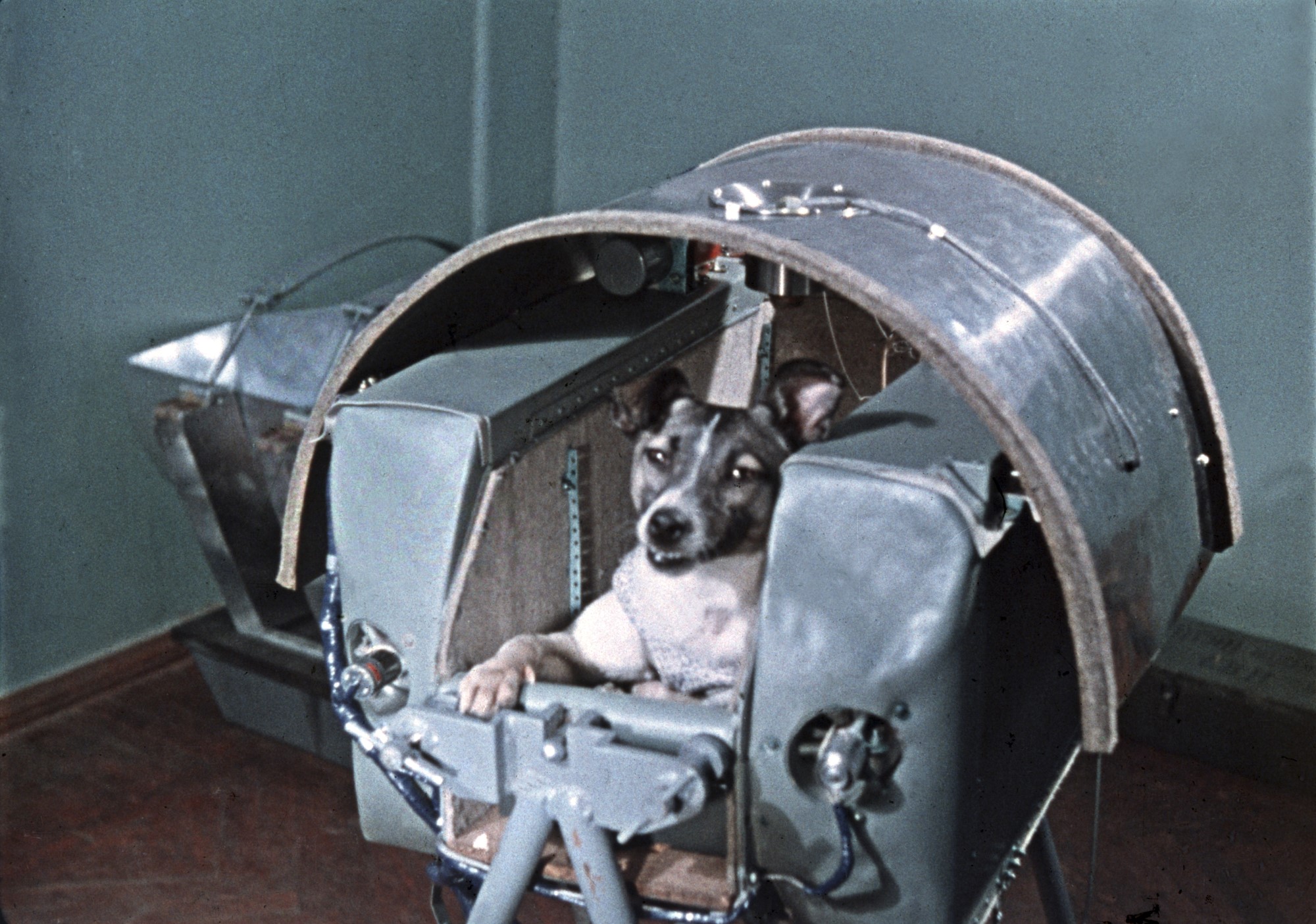

Walker: They picked dogs from the streets of Moscow. They looked for very specific kinds of dogs: females, because it is easier for them to go to the bathroom than males; mongrels, because the idea was that they would be tougher; small dogs to fit inside the space capsule; and dogs that were light colored so that they were easier to see on the cameras onboard the spacecraft. The dogs were then secretly trained at the Institute of Aviation Space Medicine in Moscow.

However, many of the dogs sent to space died during their flights, maybe more than twenty of them. Laika — the first dog in space — met a particularly tragic death in November 1957. She was sent on a one-way mission aboard Sputnik 2, and this is when we started to see reactions from animal rights activists because technologically, the Soviet Union did not have the ability to bring Laika home. She had enough food and oxygen for seven days, but would die in orbit, which excited real anger across the West. She became a real Soviet icon until Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space.

Space.com: How did animals' involvement change as the space program evolved?

Walker: Well, we don't have primates going into space any longer — Lapik and Multik [two rhesus monkeys that flew on the Bion 11 mission, a life science collaboration of the U.S., Russia and France] were the last monkeys launched to space in 1996, unless you count a possibly non-existent Iranian mission in 2013.

In later [animal] missions, they were looking to study things like muscular atrophy and whether animals and people could survive prolonged periods in space. For example, a mission in 1998 called Neurolab focused on the effects of microgravity on the nervous system. This mission had the largest number of animals accompanying seven human crew members on the space shuttle Columbia. There were 10,000 crickets, 12 cages of rats and a whole load of other animals — it was Noah's Ark.

One of the really interesting things they discovered on that mission was that many of the mother rats stopped looking after their babies in weightlessness; they were not coping with motherhood. As a result, half of the baby rats died within the first few days because they weren't getting fed, warmth or shelter from their mothers any longer.

Space.com: How did sending animals to space help pave the way to human spaceflight?

Walker: Let's take one example. Sixty years ago, Enos became the first chimpanzee to orbit the Earth on Nov. 29, 1961. His flight was a full dress rehearsal for John Glenn's own orbital flight — the first American to orbit the Earth — which took place in February 1962.

Every element of Enos's flight was designed to test the upcoming human orbital flight, using the same hardware, the same Mercury capsule, the same tracking systems and so on. In order for the Americans to ascertain whether a human could actually pilot a spacecraft, they tested the chimpanzees' ability to move levers in response to certain light cues, using a device called a psychomotor. If the chimpanzee got it wrong, they received an electric shock on their feet.

Enos was the cleverest chimpanzee — he could work the psychomotor and never make a mistake. There was one particular exercise for which they received a banana pellet as a reward if performed correctly. One of the tests required the chimpanzee to pull one of the levers exactly 50 times to receive a banana pellet. Enos got so good at this — I mean, a chimpanzee counting to 50 — that on the 49th pull he would hold out his hand ready for the pellet he knew would be coming out after the next pull. That's how good he was.

When Enos launched in November 1961, something went horribly wrong with the psychomotor inside the capsule and he received 35 electric shocks for doing the right thing. But something incredible happened here, too. It's clear from the original NASA reports that Enos understood something was wrong and actually tried to game the system by pulling the levers differently to change the situation — incredible.

These animals made terrible sacrifices, there's no doubt about it. But they did really help pave the way for human space flight. More humans would have died had animals not been used. More things would have gone wrong. The same perhaps applies today as we contemplate human missions to Mars and even beyond. But we must never forget there is always a heavy price to pay. We need to change that, and we need to remember.

You can buy "Beyond" on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.