Sudden collapse of Antarctic ice shelf could be sign of things to come

Unexpected collapse sends a massive slab of ice into the ocean.

A massive Antarctic ice shelf that covered an area about the size of New York City or Rome just collapsed into the ocean. Scientists warn that while they do not expect significant impacts as a result of this event, melting ice in this historically stable region may be a foreboding sign of things to come.

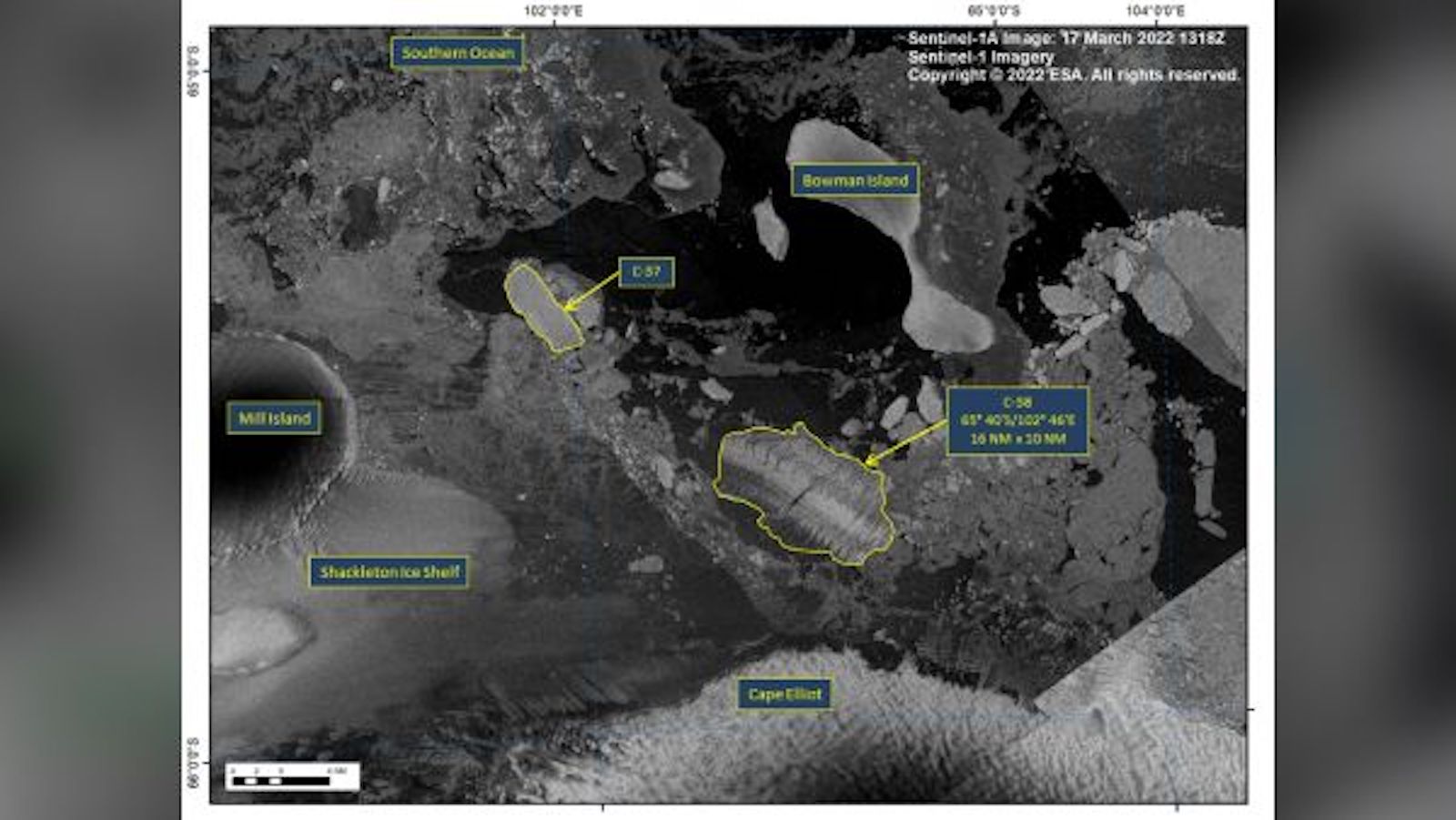

Satellite photos reveal the sudden disappearance of the Conger Ice Shelf on East Antarctica between March 14 and March 16. "The Glenzer Conger Ice Shelf presumably had been there for thousands of years and it's not ever going to be there again," University of Minnesota glaciologist Peter Neff told NPR. While the Ice shelf had been slowly shrinking since the 1970s, recently accelerated melting preceded this month's sudden and unexpected collapse.

Antarctica is divided into East and West Antarctica, with the Transantarctic Mountain Range separating the two halves. In West Antarctica, the ice is more unstable than in the east, so melting ice and collapsing ice shelves are often observed.

However, East Antarctica is one of the coldest and driest locations on planet Earth, and because of this, ice shelf collapses are unheard-of there. According to the AP, this is the first major ice shelf collapse in East Antarctica during human history.

Related: World's largest iceberg disintegrates into 'alphabet soup'

This ice shelf collapse occurred during a bout of unseasonably high temperatures in the region. Concordia Station, an Antarctic research facility located on the eastern side of the continent, reported temperatures of 10.8 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 11.8 degrees Celsius) on March 18, the warmest temperature ever recorded in March at the station. This temperature is more than 72 F (40 C) warmer than seasonal averages. These unseasonably high temperatures are the result of an "atmospheric river," which is a jet of warm, moist air that trapped heat over the region, according to a report by The Guardian. Some of that moisture even precipitated as rain.

Much of that heat from the atmospheric river was likely absorbed by water underneath the Conger Ice Shelf. NASA planetary scientist Catherine Colello Walker speculated on Twitter that heat carried by a recent atmospheric river event contributed to the shelf's sudden collapse.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Though the major collapse occurred on March 15, it was just the second of three "calving" events in the region this month, according to Helen Amanda Fricker, a professor of glaciology at Scripps Institution of Oceanography via Twitter. Fricker said that ice shelf calving events, which are so named because they give birth to icebergs, are part of the natural life cycle of an ice shelf. Because of the coinciding unseasonable heat, scientists need to explore the possibility of a climate change connection.

According to the U.S. National Ice Center, the calving events, which began on March 7, have created several icebergs. One of which, dubbed C-37, measures 8 nautical miles long and 3 nautical miles wide (14.8 by 5.6 kilometers).

While scientists don't expect any major consequences as a direct result of the Conger Ice Shelf collapse, they do warn that this could be the beginning of a troubling trend. According to Neff, ice shelves act as a buffer to protect Antarctic glaciers from melting, as they insulate those glaciers from the warm seawater. If glaciers in East Antarctica melt, they could be a major driver of sea-level rise in the coming decades.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Cameron is a contributing writer covering life sciences for Live Science. He also writes for New Scientist as well as MinuteEarth and Discovery's Curiosity Daily Podcast. He holds a master's degree in animal behavior from Western Carolina University and teaches biology at the University of Northern Colorado.