Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing

Relive the drama!

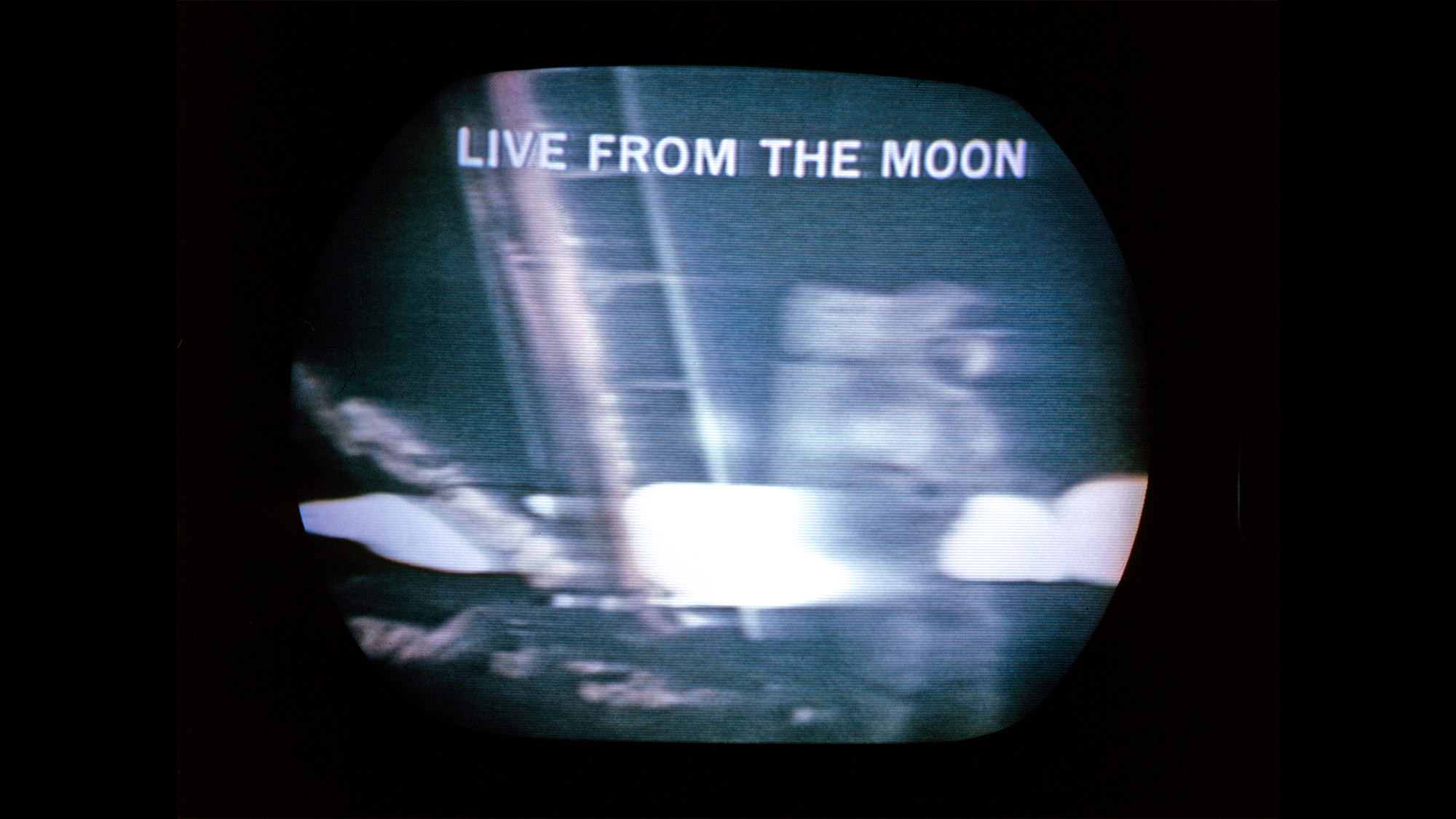

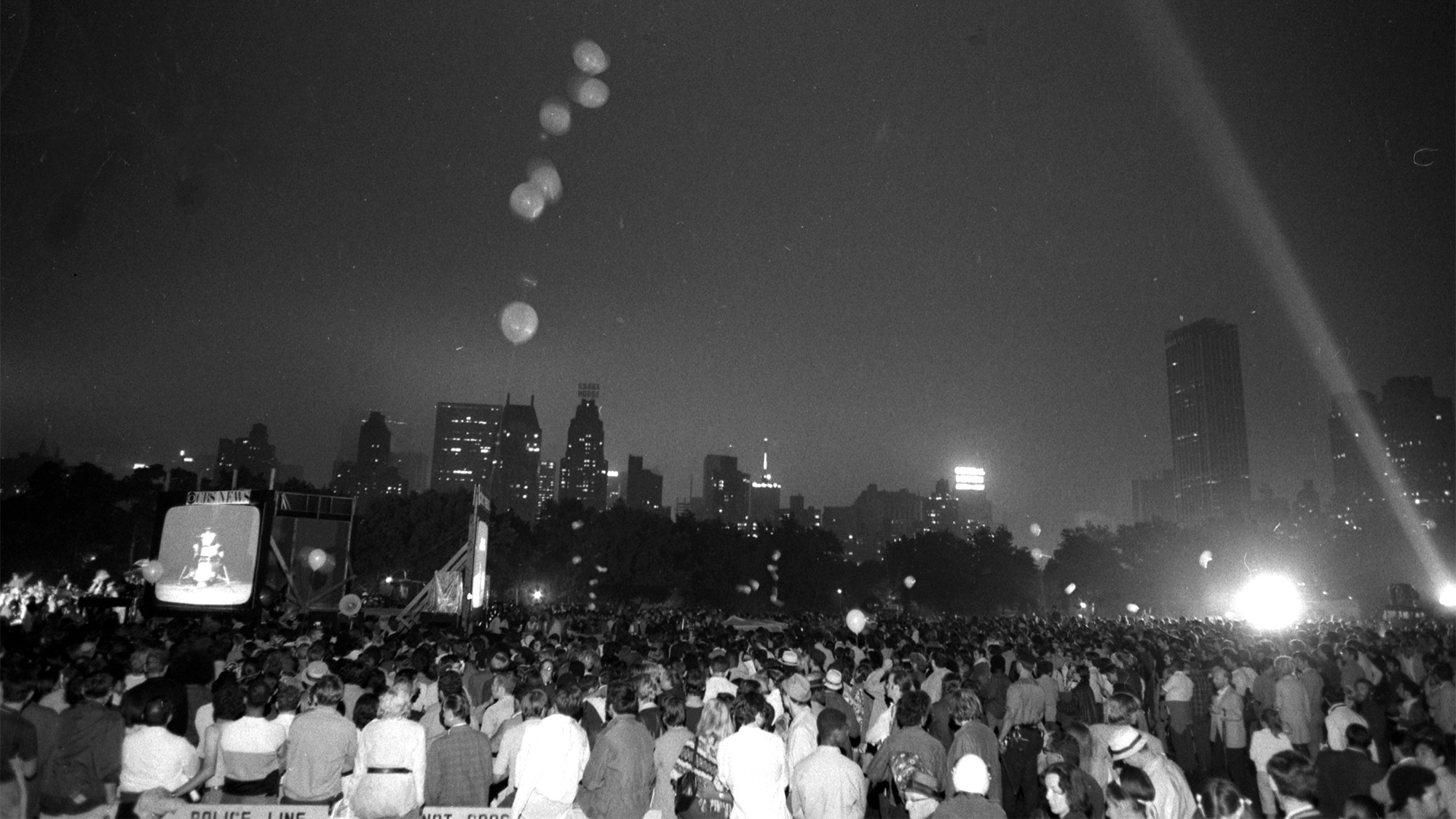

On July 20, 1969, 600 million people watched with anxious excitement as Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin Jr. took their first steps on the moon's surface.

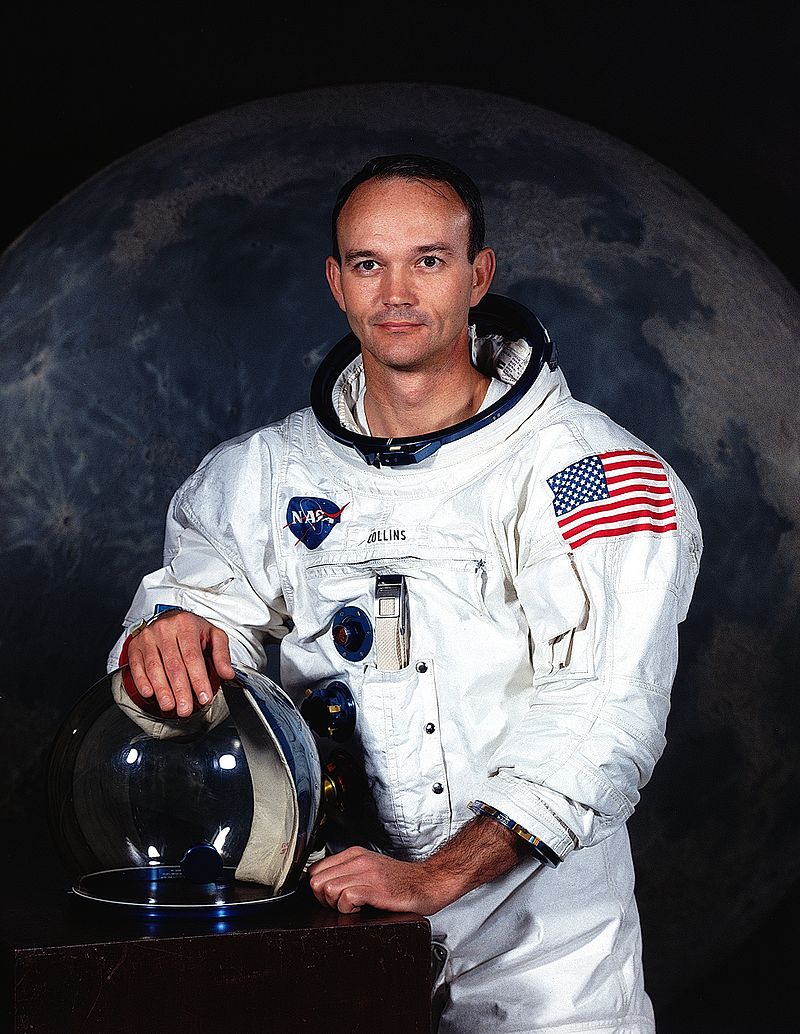

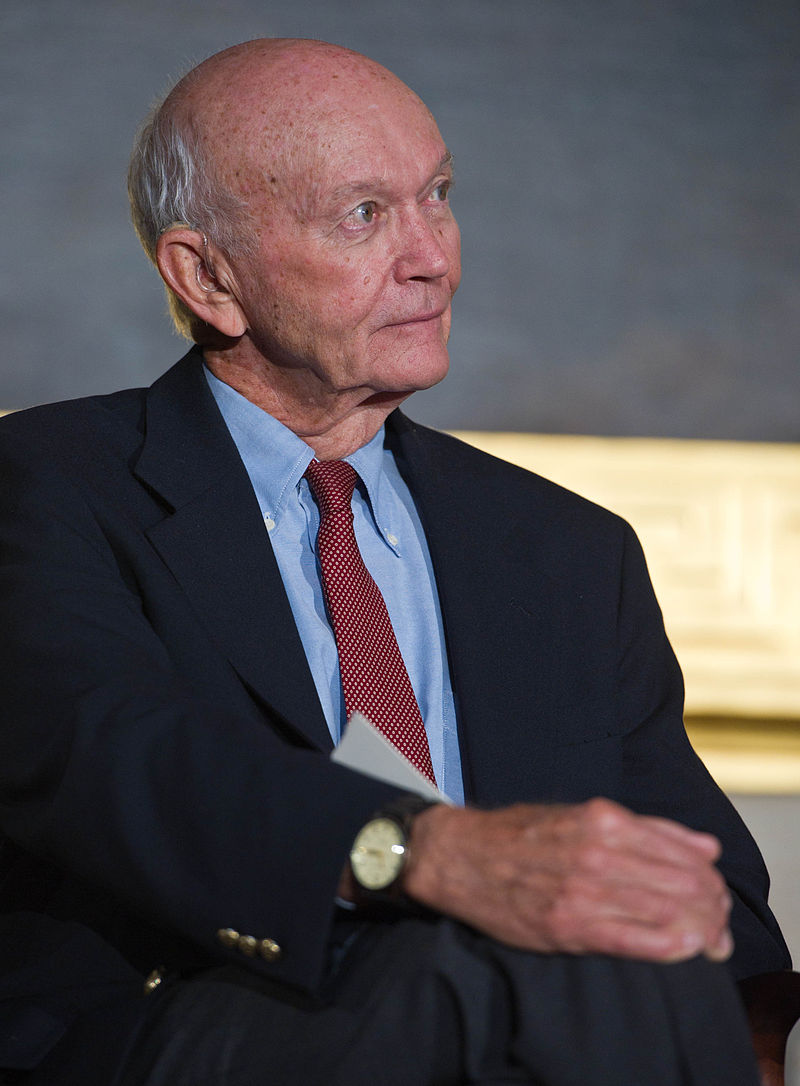

The first humans ever to leave footprints in the lunar regolith, Aldrin and Armstrong made history — and a permanent impression on the world — as they bravely ventured beyond Earth. This summer marks 50 years since Aldrin, Armstrong and Michael Collins made their daring journey to the moon.

But this historic achievement belongs to many more Americans than just this trio of astronauts: Behind the scenes, more than 400,000 people worked on the mission and made it possible for to land on the moon. All told, it was one of the greatest feats that we humans have ever pulled off.

See our complete archive of Apollo 11 50th anniversary coverage here!

- Relive Apollo 11 Moon Landing Mission in Real Time

- Apollo 11 Moon Landing Giveaway with Simulation Curriculum & Celestron!

- Events Celebrating Apollo 11 Moon Landing's 50th Anniversary

The mission, dubbed Apollo 11, was the climax of the Apollo program, which pushed human spaceflight forward faster than ever before. In October 1968, the first crewed flight of the Apollo program lifted off; less than a year later, Apollo 11 launched. Within just a few short years, a total of six missions landed 12 U.S. astronauts on the surface of the moon. A seemingly impossible goal, the first human landing on the moon was a major victory for the United States in the ongoing space race with Cold War rival the Soviet Union.

Fifty years after the Apollo 11 mission, people around the globe are once again reflecting on and celebrating the moon landing, the odds that were stacked against it and how it continues to influence spaceflight.

Slideshow: How NASA's Apollo Astronauts Went to the Moon

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

We choose to go to the moon

"We choose to go to the moon," U.S. President John. F. Kennedy famously declared in 1962 to a captivated crowd at Rice Stadium in Texas.

This speech invoked a new urgency in the space race, which had been going on between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The two Cold War rivals were both determined to outdo the other and land humans on the lunar surface first.

The U.S. efforts in this contest included two predecessors to Project Apollo: Project Mercury, which began in 1958, and Project Gemini, which followed in 1961. But until the moon landing itself, the Soviet space program was ahead overall, with successful missions including Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit Earth, and Luna 2, the first space probe to touch the moon.

"I think in America, at least, there [was] a feeling of a great lack of self-confidence, a feeling of 'We are falling behind,'" Asif Siddiqi, a space historian at Fordham University in New York, told Space.com. "Pretty much every single major event in the space race in the early days was a triumph of Soviet space achievement."

After World War II, Siddiqi explained, the U.S. was feeling on top as the country's economy grew. "There's an expectation that if anything's going to happen in science and technology, America's going to be first," Siddiqi said. But this expectation was not realized in the space race, and the Soviet Union beat the U.S. to space milestones again and again.

So, in 1961, Kennedy decided to take charge and proposed to Congress the goal of "landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth" by the end of the decade. (The idea of a moon mission was first discussed during Dwight D. Eisenhower's administration, but it's most strongly associated with Kennedy's declaration.) This seemingly impossible task quickly became the ultimate goal of the Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo.

Kennedy's famous speech at Rice Stadium the next year inspired Americans to dream big. The announcement lit a fire under the teams at NASA to complete the task on a seemingly impossible timeline.

But the ambitious goal required an equally ambitious budget. The U.S. government ended up allocating $25 billion in 1960s dollars to the Apollo program, or about 2.5% of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) at the time annually for approximately 10 years.

Project Apollo ran from 1961 to 1972, even though NASA accomplished Kennedy's goal in 1969. Although other astronauts visited the lunar surface after Apollo 11, the triumphant first landing remains a pinnacle in spaceflight history.

Trial and error

Apollo 11 was successful only because of the missions that came before it. Those flights set the stage for the lunar landing and served as the testing grounds for the burgeoning technologies and strategies that were eventually used in that mission.

Apollo 1, originally named Apollo Saturn-204 or AS-204, was to be the program's first crewed mission, set to orbit Earth with three astronauts aboard. However, tragedy struck on Jan. 27, 1967, when a fire ignited within the Apollo 1 command module while the crew was performing a prelaunch test. All three astronauts inside — Ed White, Roger B. Chaffee and Gus Grissom — died in the fire.

At the time, it seemed like the Apollo program might be over before it really even began. But the deaths instead forced NASA to improve astronaut safety requirements. The agency put crewed missions on hold while it reevaluated its systems to make sure they were safe enough to fly. The astronauts of the Apollo 1 crew would be the only fatalities of NASA's push to land on the moon. After this first disaster, NASA tested its capabilities and resolved outstanding safety issues with uncrewed missions dubbed AS-201, AS-202, AS-203, and Apollo missions 4 through 6.

Crewed flights resumed with Apollo 7, which launched on Oct. 11, 1968, orbited Earth for more than a week and splashed back down on Oct. 22. Aboard Apollo 7, the crew demonstrated the functionality of the command and service module. The mission also showcased how the mission-support facilities could work together with the vehicles and the crewmembers.

Apollo 7 was soon followed by the first Apollo lunar mission, Apollo 8, which launched on Dec. 21, 1968, and returned home a week later, on Dec. 27. Apollo 8 was a major step forward in the program, as it was the first flight that took humans beyond low-Earth orbit to the moon’s orbit and back again.

The Apollo 8 mission was an important testing ground for the spacecraft systems and navigation techniques that NASA had developed for approaching and orbiting the moon. These systems and techniques made the future lunar landing possible.

Additionally, on this flight, astronaut Bill Anders took the famous "Earthrise" photo, showing the planet seeming to hover above the moon's surface. Besides being "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken," as nature photographer Galen Rowell said, the image showed the incredible progress that had been made in human spaceflight.

Apollo 9 soon followed, launching on March 3, 1969, and splashing down just over a week later, on March 13, after orbiting Earth. During this mission, the Apollo 9 astronauts tested all aspects and functionalities of the lunar module in Earth orbit and demonstrated that the craft could operate independently as it performed its docking and rendezvous maneuvers. These tests mimicked what NASA expected would happen during a lunar landing.

The Apollo 10 mission flew a command and service module dubbed "Charlie Brown" and a lunar module known as "Snoopy." This mission, which launched on May 18, 1969, just two months before Apollo 11, proved that the crew, the vehicles and the mission-support facilities at NASA were prepared for a lunar landing. The mission was a "dry run" for the moon landing, as the Apollo 10 astronauts performed all of the operations that were scheduled for Apollo 11 except for the actual moon landing.

All of this hurried preparation paved the way for NASA to finally launch the Apollo 11 mission — astonishingly less than a year after the first successful crewed Apollo flight.

Inside the spacecraft

When it was finally time to send humans to the moon, NASA decided to launch the mission on a Saturn V rocket.

That rocket lofted three modules into Earth's orbit, including the command module to carry the astronauts to and from the moon and the lunar module to land Aldrin and Armstrong on the surface.

Saturn V

The massive Saturn V rocket stood an impressive 363 feet (111 meters) tall on Launch Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The Saturn V was a type of extremely powerful rocket known as a heavy lift vehicle, and with a liftoff thrust of 7.6 million lbs. (34.5 million newtons), Saturn V is not just the tallest but also the most powerful rocket ever launched. (After the Apollo program, the ultrapowerful rocket was used to launch the Skylab space station.) The rocket's first crewed launch was Apollo 8.

Saturn V weighed 6.2 million lbs. (2.8 kilograms) and could launch about 50 tons (43,500 kg) of cargo and crew to the moon. For the Apollo program, the Saturn V was outfitted with three stages. The first stage had the most powerful engines on the rocket, to lift the craft off the ground.

This first stage separated from the rocket with the "dead-weight" launch escape tower, leaving the second stage to carry the rocket almost into orbit. The third stage then broke the vehicle out of Earth's orbit and sent it toward the moon.

Related: Could NASA Build the Saturn V Today? It's Working on It, with a Twist

Apollo spacecraft

On top of the Saturn V rocket, Apollo 11 launched the command and service module — made up of the service module and the command module spacecraft — and the lunar module spacecraft.

The command module housed the astronaut crew along with the spacecraft's operation systems and the equipment needed for reentry. Standing 10.6 feet (3.2 m) tall and 12.8 feet (3.9 m) wide at its base, the command module didn't leave much room for the astronauts inside to move around. At 210 cubic feet (6 cubic m), the space inside of the command module has been compared to the interior of a car.

The command module was made up of three compartments — the forward compartment in the nose cone, the aft compartment at the base of the module and the crew compartment. The forward compartment held parachutes for the Earth landing, while the aft compartment held propellant tanks, reaction-control engines, wires and plumbing. Within the crew compartment, astronauts sat on three couches facing forward in the middle of the craft, which offered the crew an opportunity to look out through five windows. The command module was also powered by five silver/zinc-oxide batteries that which supported the craft in reentry and landing after it separated from the service module.

One of the command module's most important features was its heat shield, which allowed the spacecraft to survive incredibly hot temperatures while reentering Earth's atmosphere.

For most of the Apollo 11 mission, the service module was attached to the back of the command module. Holding fuel tanks, fuel cells and oxygen/hydrogen tanks, the service module provided the command module with power, propulsion and room for additional cargo. A cylinder-shaped craft, the service module was 24.6 feet (7.5 m) long and 12.8 feet (3.9 m) in diameter.

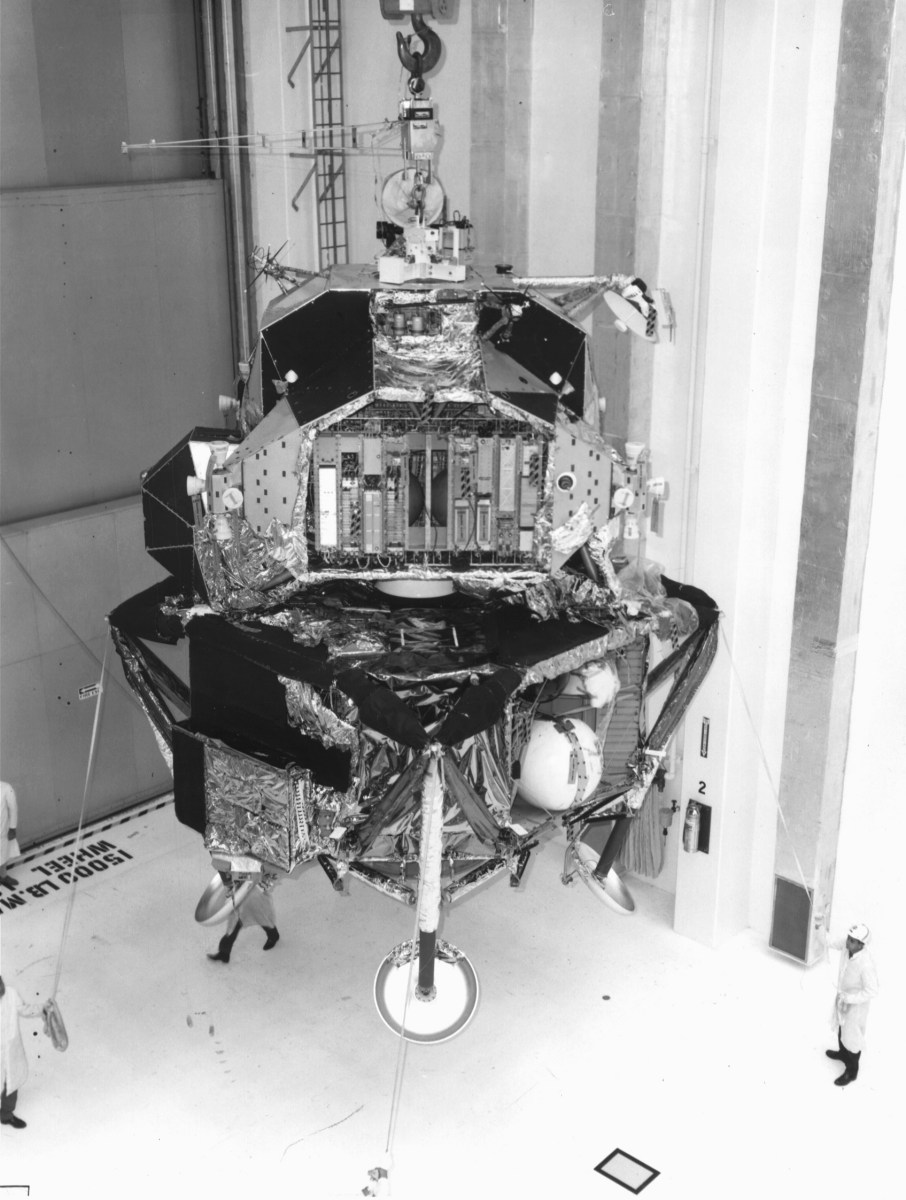

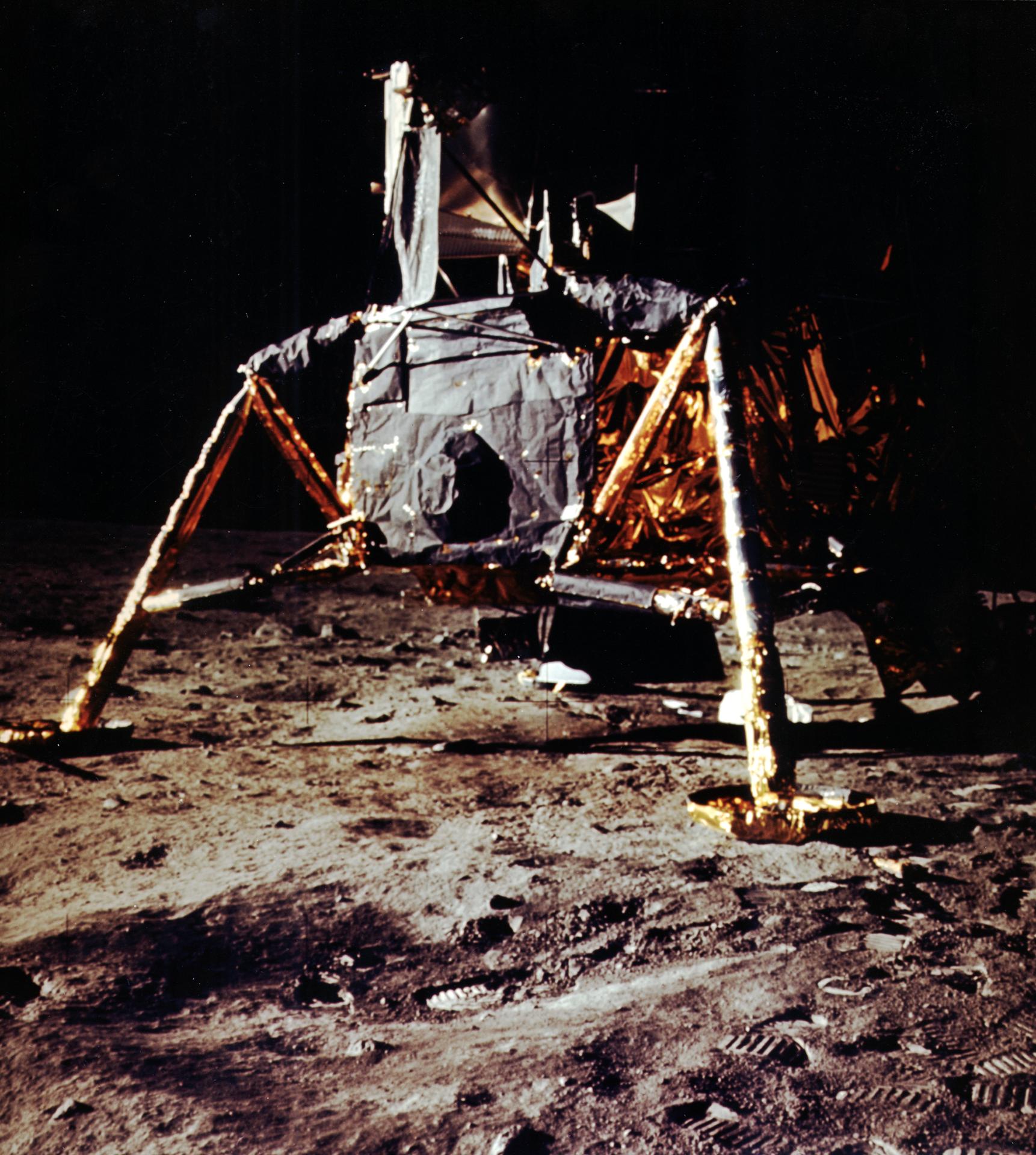

Sitting beneath the command and service module, the Apollo 11 lunar module, also known as "Eagle," was the final piece of the Apollo puzzle and carried Aldrin and Armstrong to the lunar surface during the historic mission. At 23 feet (7 m) tall and 14 feet (4 m) wide, the lunar module was made up of an upper ascent stage and a lower ascent stage.

After Collins inspected the lunar module, Aldrin and Armstrong undocked it from the command and service module and headed for the lunar surface, leaving Collins to orbit the moon. The Apollo lunar modules were the first crewed spacecraft to operate only in space.

In addition to the astronauts themselves, the lunar module contained the Early Apollo Scientific Experiment Package. That package held a number of self-contained experiments that were designed to be left on the lunar surface.

The package also held additional scientific instruments and equipment for sample collection on the surface. Apollo 11 carried the first geological samples from the moon back to Earth. In total, Armstrong and Aldrin collected 48.5 lbs. (22 kilograms) of material from the moon, including 50 moon rocks, lunar soil, pebbles, sand and dust. The astronauts also sampled material from more than 5 inches (13 centimeters) below the lunar surface.

Related: Why the Lunar Module Looked So Much Like a Moon Bug

The impact of Apollo

An estimated 600 million people around the world watched as Armstrong and Aldrin left the first footprints on the lunar surface. The landing marked not just a historic milestone, but also the end of the Cold War space race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The Apollo program brought more missions and more landings, but Apollo 11 marked an unparalleled victory for the U.S.

But the geopolitical tension had done more than just intensify the race to the moon; it also ignited a fevered excitement about space. Americans of all ages idolized the NASA astronauts.

"They were rock stars," former NASA astronaut Mike Massimino told Space.com earlier this year. As Siddiqi said, the "sort of clean-cut, all-American archetype" was a positive diversion from the massive problems that plagued the U.S. at the time. The civil rights movement was growing in response to the incredible inequalities in the country as both the Cold War and Vietnam War continued. The Apollo astronauts were the romanticized, larger-than-life heroes that people could admire during those difficult times.

"The cultural imagery, the imagination of Apollo is very powerful if you think about the pictures and the astronauts," Siddiqi said. And this superheroic imagery was only amplified as science fiction novels and movies continued to grow in popularity. Many people viewed a journey to the moon as the ultimate adventure and the Apollo astronauts as the perfect hero leads.

The romanticization of the lunar landing program permeates space exploration even today. Fifty years after Apollo, NASA has sent spacecraft out beyond Pluto, to the surface of Mars and to the sun. Researchers have discovered exoplanets with Earth-like qualities, and our knowledge of the solar system and the universe at large has become profoundly more detailed over the decades.

But many still view the Apollo 11 lunar landing as the greatest achievement in spaceflight. People who remember watching the landing on television still recall the moment as if magic had been made real before their eyes.

We choose to return to the moon

Humans haven't stepped foot on the lunar surface since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. For decades, people have wondered why we haven't returned to the moon, and presidential administrations have toyed with the idea of doing just that. But currently, the moon is having a moment, and NASA has again set its aim on landing humans on the lunar surface.

President Donald Trump's administration recently announced a new, aggressive timeline to return astronauts to the moon. On March 26, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence announced that the U.S. would aim to land humans on the moon within the next five years.

According to NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, the agency will address that goal first by sending a crew close to the moon by 2022, then landing humans at the moon's south pole by 2024. Bridenstine said this timeline will allow for a Mars landing by 2033.

The new moon push, which has been dubbed the Artemis program, is also meant to be longer-lived than the Apollo program. "This time, when we go to the moon, we're going to stay," Bridenstine said at NASA headquarters on Feb. 14.

The space agency has tenuous plans to build a space station that will orbit the moon as a platform for astronauts to use to reach more-diverse sites on the lunar surface. Pence said the administration's plan also includes a permanent lunar base.

But NASA isn't alone in its quest to return humans to the lunar surface. Instead, the agency is looking to build partnerships with other countries and with U.S. businesses. So far, the agency has hired Maxar to build the power and propulsion element of the lunar Gateway space station; NASA also announced that it would purchase rides to the lunar surface from Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines and Orbit Beyond for the agency's first Artemis program science experiments and technology demonstrations.

Other companies are looking to reach the moon on their own. SpaceX, for instance, has publicly stated that it intends to fly private citizens around the moon. Israeli startup SpaceIL's robotic Beresheet mission ended with a crash, but the team has already expressed interest in building a new lander.

Other countries also have their eyes on the moon. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) is working to land astronauts on the moon by 2029 and is even designing a vehicle with Toyota to explore the lunar surface.

In the nearer term, two lunar missions may launch this year. China opened the year by becoming the first country to land on the far side of the moon, with the robotic Chang'e 4 mission. And the country is targeting its next launch, of the Chang'e 5 sample-return mission, for later this year.

India has also been pursuing both crewed and robotic missions to the moon. That country plans to launch Chandrayaan-2, which includes an orbiter, a lander and a rover, later this year.

Apollo 11 Giveaway!

- How the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Worked (Infographic)

- Apollo 11 Moon Rocket's F-1 Engines Explained (Infographic)

- Remembering the Apollo 1 Fire (Infographic)

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.