50 Years On, Where Are the Surveyor 3 Moon Probe Parts Retrieved by Apollo 12?

Fifty years ago, two astronauts became the world's first space archaeologists, of a sort, retrieving parts from a robotic probe that preceded them to the surface of the moon. Half a century later, where have those Surveyor 3 artifacts ended up today?

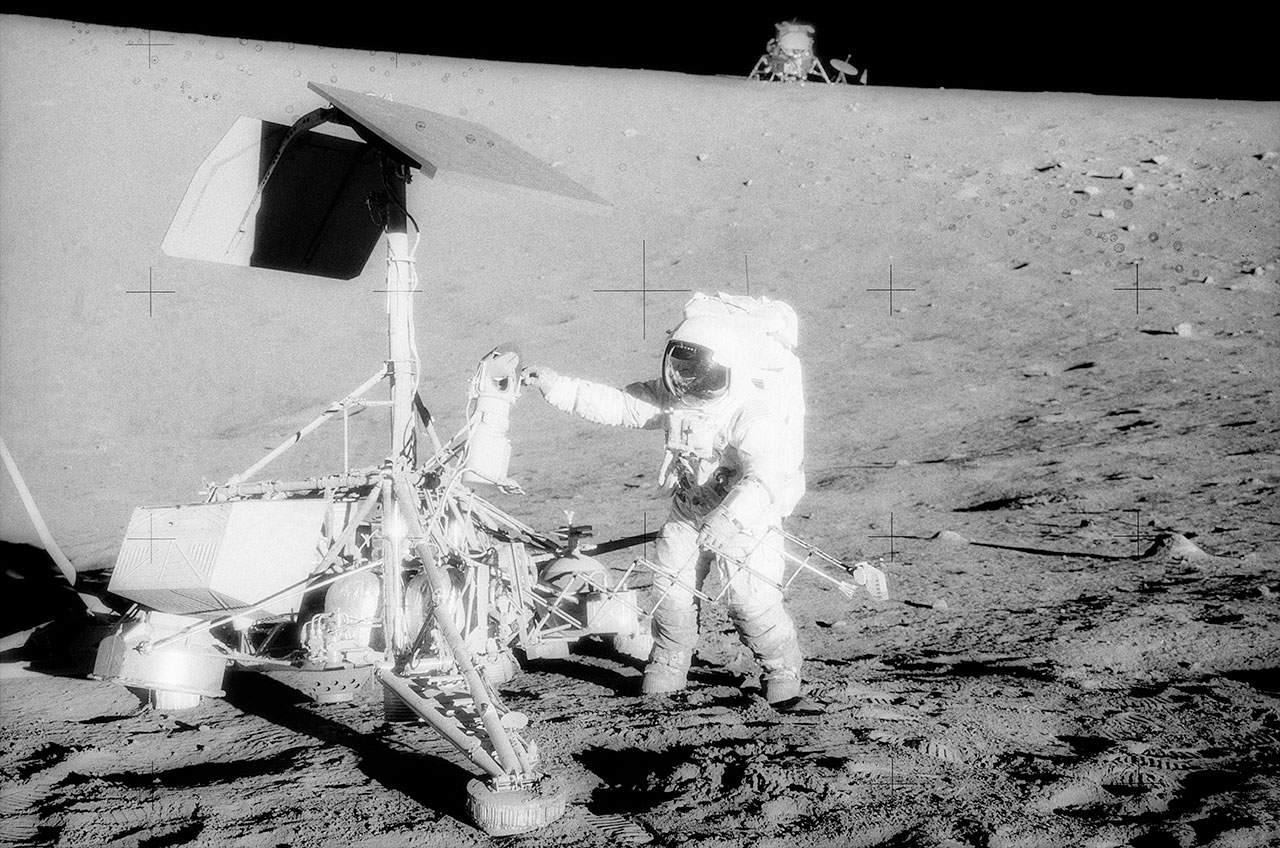

Apollo 12 crewmates Charles "Pete" Conrad and Alan Bean achieved the first precise lunar touchdown on Nov. 19, 1969, landing within walking distance of the Surveyor 3 spacecraft. On their second of two moonwalks, Conrad and Bean ventured over to the robotic probe, which by then had been on the moon for two and a half years.

"Hey, we got a nice brown Surveyor here ... well, raise the visor and it's not so brown, but it's tan," described Bean as he lifted his helmet's gold-coated visor to get a clear look at the previously white lander.

Related: Apollo 12 in Pictures: NASA's Pinpoint Moon Landing Mission

More: Apollo 12 Had the Funniest Crew. Here's Why

A short time later, as he and Conrad continued to inspect Surveyor, Bean found it was not tan, or brown, after all.

"We thought this thing had changed color, but I think it's just dust," said Bean. "We rubbed into that battery, and it's good and shiny again."

Following their training and checklists, the astronauts collected a scoop from the probe's soil mechanics-surface sampler, a section of unpainted aluminum tube from a strut supporting the Surveyor's radar altimeter and Doppler velocity sensor, another section of aluminum tube that was coated with inorganic white paint and a segment of television cable wrapped in aluminized plastic film.

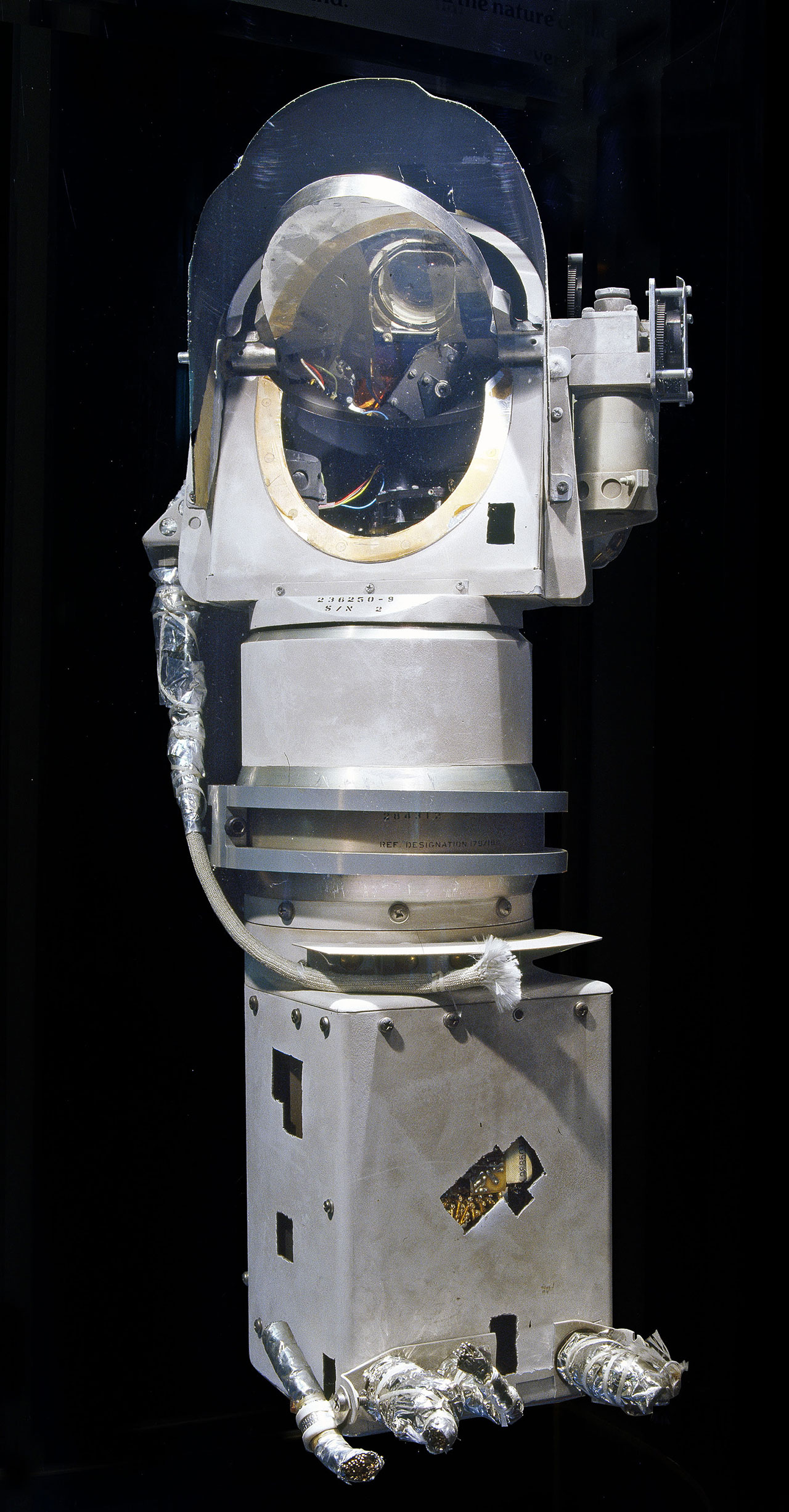

And there was the Surveyor's camera.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"That's ours!" exclaimed Conrad, as the camera came loose.

"We got her!" replied Bean.

The Apollo 12 moonwalkers returned the camera and other parts to their lunar module, "Intrepid." Later that same day, 31 hours after they arrived, Conrad and Bean lifted off of the moon to rendezvous with their third crewmate, Richard "Dick" Gordon, on the command module "Yankee Clipper" and begin their journey back to Earth. Accompanying them were 75 pounds (34 kilograms) of moon rocks and 20 pounds (9 kilograms) of probe hardware.

Related: Truth of the Moon: The Brave Voyage of Apollo 12 | Video Show

Surveying Surveyor

Like the moon rocks, the Surveyor 3 parts were returned to Earth for study. For the first time, scientists and engineers had an opportunity to analyze equipment after it being subjected to long-term exposure on the lunar surface.

"The returned material and photographs have been studied and evaluated by 40 teams of engineering and scientific investigators over a period of more than one year," wrote Surveyor program manager Benjamin Milwitzky in the 1971 report on the studies' findings.

More than 80 researchers carefully examined the returned Surveyor parts for the effects of radiation and lunar dust exposure. As it turned out, Conrad and Bean had been correct — Surveyor 3 did change color and it was partly due to lunar dust adhesion. Sun exposure, over the course of 32 lunar days, had also caused paint to fade.

Related: How a Passionate Scientist's Eye Led to the 1st Pinpoint Moon Landing

The engineering studies found that the TV camera and other hardware exhibited no signs of failure, which led Milwitzky to conclude, "that the state of technology, even as it existed [prior to the Surveyor 3 launch in 1966], is capable of producing reliable hardware that makes feasible long-life lunar and planetary installations."

Other studies looked at the probe's equipment for the effects of the solar wind and micrometeorite impacts. About the latter, the research concluded that none of the visible surface features were of meteoritic origin.

Bacteria that was found within the television camera was initially thought to have been deposited before Surveyor 3 was launched to the moon, meaning that it had survived for 31 months on the moon. Later studies found that it was more likely to have been the result of contamination from the team inspecting the camera after it was returned to Earth, as a result of poor clean room procedures.

Surveyor souvenirs

After the studies were complete, NASA placed some of the Surveyor 3 parts into storage, alongside the moon rock and soil samples being preserved by the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (later, Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility) at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Others made their way to museums — and elsewhere.

"NASA treats them as lunar samples, not as artifacts," said Michael Neufeld, a senior curator in the space history department at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. "We have the Surveyor 3 camera on loan."

The television camera is currently in storage, as the gallery where it has been exhibited is being renovated. It is expected to return to display with the opening of the new Exploring the Planets exhibition in 2022.

The Cosmosphere space museum in Hutchinson, Kansas exhibits the scoop from the soil sampler, which is also on loan from NASA. Another piece of the sampler is on display at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

NASA also loaned or gifted Surveyor 3 parts to some of its leaders. Before arriving at the Smithsonian, the Surveyor 3 camera was presented to William Pickering on his retirement as the director of JPL in 1976.

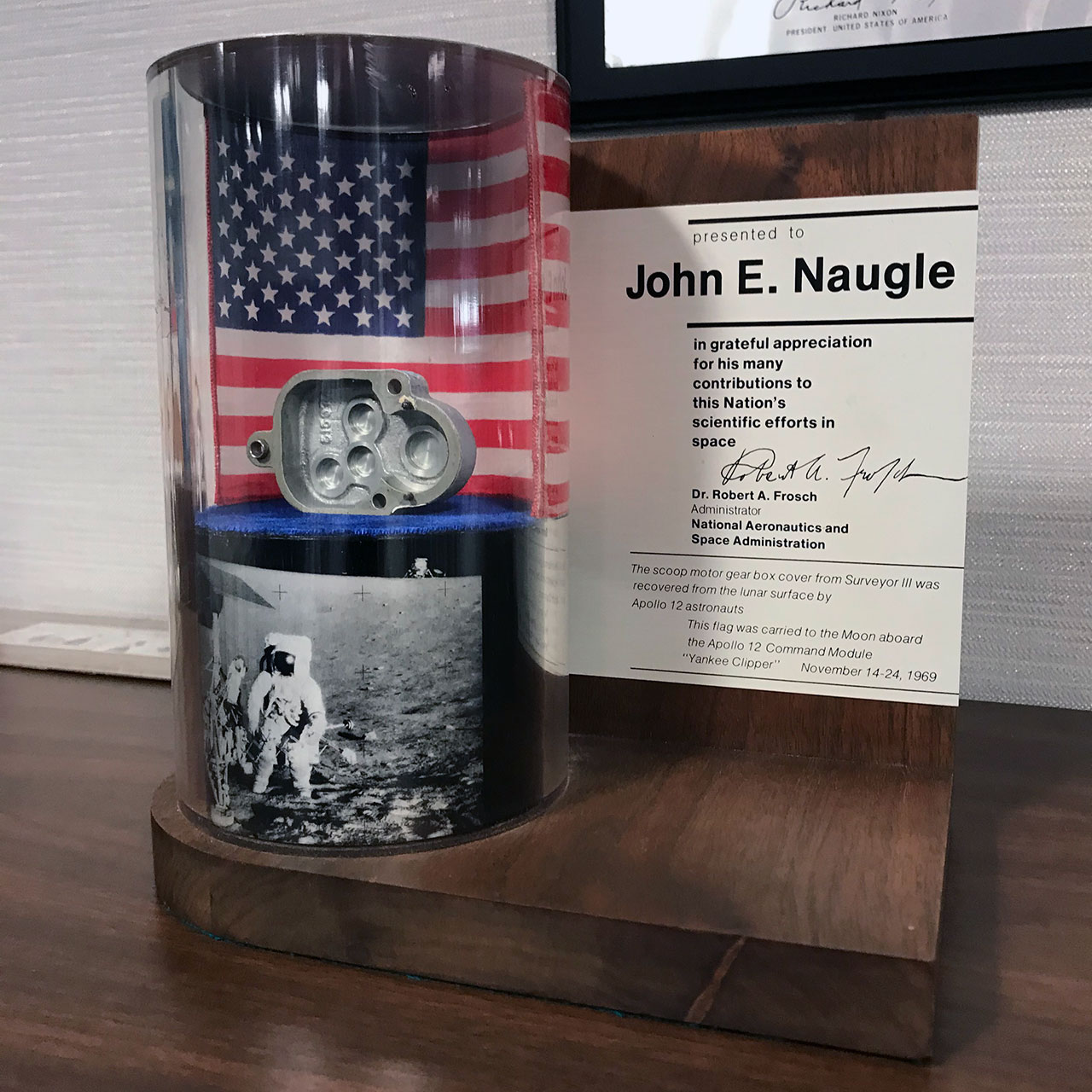

The sampler scoop's motor gear box cover was placed with an American flag that was flown on Apollo 12 in a clear tube and mounted on a wooden base for presentation to NASA's chief scientist John Naugle for his "many contributions to the nation's scientific efforts in space." After Naugle's death in 2013, his family returned the display to NASA's headquarters in Washington, DC, where it is today.

"When John Naugle's daughter returned the Surveyor 3 memento to us, it had a sticker on the bottom that said something like, 'To be returned to NASA,'" wrote Bill Barry, NASA's chief historian, in an email to collectSPACE.com.

Another piece, the color filter wheel from the television camera, remains in private hands. NASA presented the Surveyor 3 artifact to Edgar Cortright, director of Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, from 1968 to 1975. After he died in 2014, Cortright's son confirmed that NASA considers the filter wheel to be his family's property, but has plans to eventually share it with the public.

"While I do intend to donate it at some point as I think it belongs at the museum, I decided to hold onto it for a while as a memory of my father," said Dave Cortright.

That pieces were loaned or gifted as souvenirs is not unheard of, said Neufeld.

"There is some precedent from human [spaceflight] missions, people would take things out of the spacecraft and turn them into gifts or the astronauts would take things home," he said. "So there has been this tradition of turning these things into awards for people at NASA."

That said, both Barry and Neufeld agree that having the Surveyor 3 parts available today, 50 years after they were returned to Earth, has merit.

"There is much to be learned from Surveyor 3," said Barry. "Studying the Surveyor artifacts currently on Earth again with new techniques could, I presume, bear new information."

"[They are] something that were on the moon that you can look at, something that was recovered from the moon and is in the spectacular pictures from Apollo 12 of the astronauts at Surveyor," said Neufeld. "You can say, 'That thing in this photo is this object that is sitting right in front of you.”

Click through to collectSPACE to see more photos of the Apollo 12-retrieved parts of the Surveyor 3 probe.

- Apollo 12 Was Struck By Lightning Right After Launch ... Twice!

- Astronauts on Space Station Pay Tribute to Apollo 12's 50th Anniversary

- Truth of the Moon: The Brave Voyage of Apollo 12 | Video Show

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2019 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.