NASA jettisons Apollo moon landing stats to reach 300th American spacewalk

To prepare for two of its astronauts marking a new milestone in space, NASA has decided to rewrite the records for many of its historic missions, including the first moon landing.

As history records, Apollo 11 crew members Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin performed the first-ever moonwalk on July 20, 1969, 51 years ago Monday. The astronauts' 2-hour, 31-minute and 40-second outing to explore the lunar surface was recorded by newspapers, historians, authors and by NASA, itself, as the mission's only extravehicular activity, or EVA, the technical term for spacewalks.

But with a recent press release, NASA effectively added a second EVA to the first moonwalkers' credit — and the agency did not stop there. It has now changed its log books to add an additional EVA to the second, third, fourth and fifth moon landings and increased the count for the sixth and last Apollo lunar landing by two.

Related: NASA's moonwalking Apollo astronauts: Where are they now?

This was not a mistake, a NASA spokesperson said. "The EVA office triple checked their stats." Rather, the change was made on purpose, though what that reason was was not explained.

"[The] definition of an EVA with a crew member exposed to vacuum evolved throughout the years and definitions changed somewhat regarding the semantics of what constituted an EVA for history," the official at Johnson Space Center in Houston told collectSPACE.

Throwing out history

The July 13 press release that hinted at this new approach to EVA accounting was not about the Apollo missions, but rather an upcoming spacewalk outside of the International Space Station. Scheduled for Tuesday (July 21), Bob Behnken and Chris Cassidy will exit the orbiting lab to remove ground-handling fixtures from a set of solar arrays and begin preparing for the installation of a commercial airlock.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When Behnken and Cassidy venture out, [they will be] on the 300th spacewalk involving U.S. astronauts since Ed White stepped out of his Gemini 4 capsule on June 3, 1965," NASA stated in its release.

Three hundred U.S. spacewalks in 55 years certainly merits attention. There was only one problem, though. According to several independently-maintained lists of spacewalks, Tuesday's EVA would be number 293.

NASA did not share its own list (assuming that it maintains one), but provided a breakdown by spacecraft and type of airlock. The answer, it appeared, was in a note included with the "astronauts on the moon" total.

"...including stand-up EVAs to discard trash."

Setting aside that "stand-up EVAs" and trash jettisons were treated as different activities in the past, the note identified the source of the discrepancy: the seven times that Apollo astronauts depressurized their lunar modules to toss out spent equipment before lifting off from the moon to return to Earth.

On Apollo 11, Armstrong and Aldrin re-donned their spacesuits about two and half hours after their moonwalk, plugged in an umbilical to tap into their lander's air supply and opened the hatch to toss out their bulky life support system backpacks and other hardware to offset the weight of the moon rocks they were bringing home. The jettison took less than 10 minutes and did not involve either of them leaving the cabin. They simply pushed (or as later crews did, kicked) the items out the door and onto the surface.

Redefining 'EVA'

In 1997, NASA's history office published its seventh "Monograph in Aerospace History," an EVA chronology. In "Walking to Olympus," co-authors David Portree and Robert Treviño described what constituted a spacewalk.

"A U.S. astronaut must have at least his [or her] head outside his [or her] spacecraft before he [or she] is said to perform an EVA," Portree and Treviño wrote.

The reasoning behind this, the authors explained, was that during the Gemini and Apollo programs, the astronauts had to depressurize their spacecraft cabins to perform a spacewalk. That meant, for example, that while both the commander and command pilot on a Gemini mission were in vacuum, only the pilot who exited the capsule received credit for the EVA. (It is unclear if NASA's revised count now adds an EVA to each of the Gemini commanders' records, as well.)

"Walking to Olympus" neither mentions nor counts the Apollo trash jettisons. Nor does NASA's Apollo 11 mission summary on its website.

"The entire EVA phase lasted more than two-and-a-half hours, ending at 111 hours, 39 minutes into the mission," NASA wrote in its summary of the first moon landing. The trash jettison (now second EVA) began at 114 hours and 8 minutes.

Aldrin did liken the steps needed to get ready for the trash jettison as "another EVA prep exercise" during his post-flight debrief and the Apollo 17 moonwalkers made a one-time reference to their second trash jettison as being EVA-5 (on account of their three moonwalks and two jettisons).

It is not clear who specifically was involved in making the change or why it was made now.

Ripple effects

By adding the seven Apollo trash jettisons to the record, Behnken and Cassidy now get to claim making the 300th U.S. spacewalk on the same outing when they will tie the American record for the most career EVAs at 10 (as previously logged by Michael Lopez-Alegria and Peggy Whitson).

The EVA recount also realigns the tally such that Behnken also performed the 200th U.S. spacewalk with fellow STS-123 astronaut Michael Foreman on March 22, 2008. Previously, the 200th American EVA was recorded as being conducted by Stephen Bowen and Shane Kimbrough during STS-126 a month later.

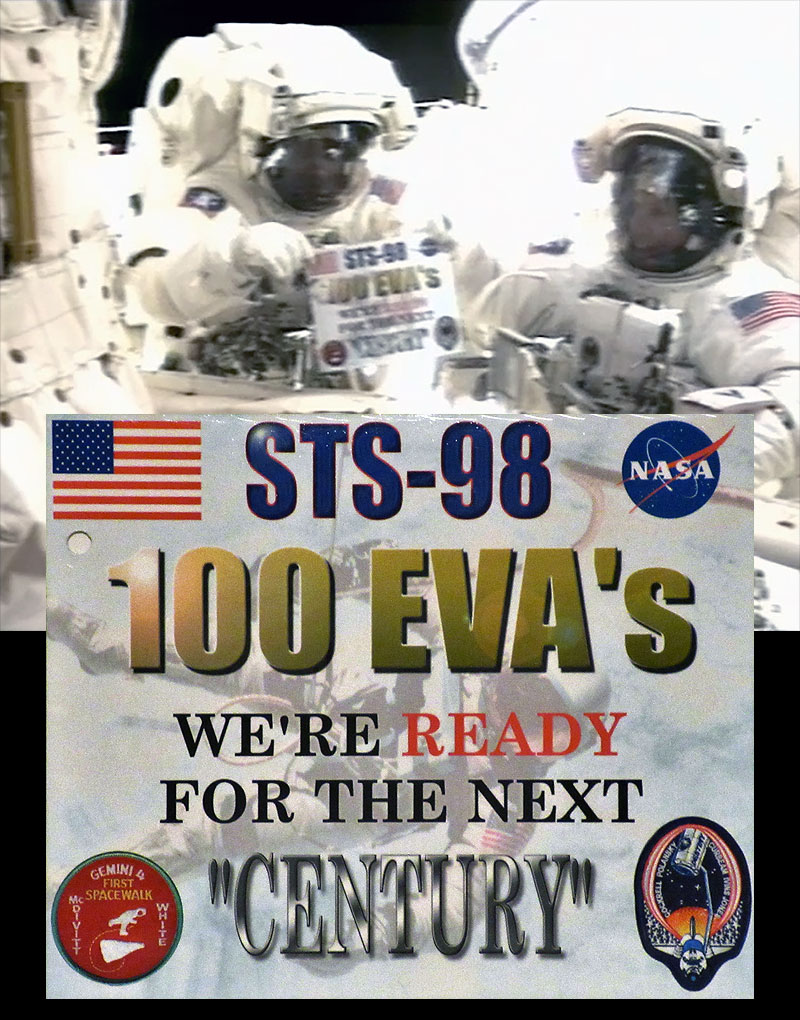

Unlike the (original) 200th U.S. EVA, though, which seemed to go by without any fanfare, NASA made a point of highlighting the 100th U.S. spacewalk when it was (thought to be) happening in February 2001.

"On STS-98, we carried out the 100th spacewalk by Americans," said astronaut Tom Jones, as he and Bob Curbeam floated outside the space shuttle Atlantis and International Space Station holding up a sign that read, "STS-98 100 EVA's, We're Ready For The Next 'Century.'"

With the addition of the Apollo trash jettisons, however, the 100th American EVA was performed by Lopez-Alegria and Jeff Wisoff on STS-92 in October 2000.

"I think it would be nice for them to be consistent," said Jones, when reached for comment on the renumbering by collectSPACE. "It would be nice to be able to take advantage of the opinions and input from all the communities that have worked EVA over the last half a century and I'd be glad to be invited to serve on that committee."

Until then, Jones said, he intends to keep his record.

"I was on the 100th EVA on STS-98 and I'm not giving it back," said Jones, with a laugh. "I've got the back-up placard for the one I carried outside and I'm not giving that back. They are not going to change the number on it."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2020 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.