How souvenirs standing in for moon rocks helped save Apollo 13 fifty years ago

After the oxygen tank exploded, after looping around the moon and the course correction that put them back on the right path to Earth, the Apollo 13 astronauts still had a problem.

Missing moon rocks.

Fifty years ago today (April 16), as Jim Lovell, Fred Haise and Jack Swigert began preparing their command module, "Odyssey," to enter Earth's atmosphere, the fact that Apollo 13 did not land on the moon became a new concern.

Related: NASA's Apollo 13 mission of survival in pictures

"One thing," Swigert radioed to Mission Control, "I guess you probably all have considered it, but what heavy things can we store down there, where the SRCs normally go, to help increase our L over D?"

In other words, what items could the crew move from their lunar module-turned-lifeboat, "Aquarius," into Odyssey's lower equipment bay to replace the sample return containers (SRC) that, had the mission gone to plan, would have been filled with about 95 pounds (43 kilograms) of lunar rocks and soil? A proper weight balance was needed to maintain the command module's lift (L) over drag (D), so that it would not burn up plummeting back to Earth at the wrong angle.

"We could probably put some cameras, television cameras, things like that, that are normally pretty heavy, down there," said Swigert, "[But] anything else you can think of would be greatly appreciated."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronaut Jack Lousma, serving as capsule communicator, or capcom, in Mission Control in Houston, replied that he would get somebody to work on that. About half a minute later, he offered his own suggestion.

"Souvenirs, I guess," he said.

"What souvenirs?" Swigert replied, laughing. "All I've got is a Marine Corps foxhole digging shovel."

"You've got all you need then, buddy," said Lousma, a Marine Corps pilot.

As it turned out, Lousma's joke was not too far from what followed. About 12 hours later, after a shift change in Mission Control, the packing instructions were ready.

"I have an entry stowage list to give you, which specifies which equipment will be moved between vehicles before splashdown," radioed Vance Brand, who relieved Lousma at the capcom console.

"Okay, Vance, we're ready to cover — to copy the stowage list," replied Lovell.

Mission Control's makeshift moon rocks included a data recorder; the lunar module checklists (flight data file); the 16-millimeter and 70-millimeter film exposed during the mission; oxygen hoses; two lunar surface Hasselblad still cameras and a black and white television camera.

Also on the list were any of the crew's used fecal bags from on board Aquarius, but Mission Control thought twice about that and called up to the crew to halt that transfer.

"Okay," said Haise. "We didn't have any of those, so that didn't pose any problem anyway."

Brand also had Lovell and Haise move over their personal preference kits (PPKs) — small pouches filled with mementos that were intended to land with them on the moon — as well as a kit that included 25 U.S. and 50 individual U.S. state flags, each 4 by 6 inches (10 by 15 cm).

The larger flag that Lovell and Haise would have planted at their Fra Mauro landing site was stowed in a compartment on the exterior of the lunar module, so it was inaccessible to return to Earth.

What was in reach and did come back, though, was a metal plaque that Lovell and Haise would have used to cover a similar marker attached to Aquarius' ladder. The revised plaque named Swigert instead of Thomas "Ken" Mattingly, who had been exposed to the German measles and replaced on the Apollo 13 crew days before the mission's launch.

Lovell and Haise also took it upon themselves to collect a few more "moon rocks" for good measure — and memorabilia.

Lovell detached a mirror and the crewman optical alignment sight (COAS) from above the commander's window in the lunar module, while Haise collected some of the netting used to restrain items and the four armrests from below Aquarius' control stations. The two also cut off their patches from the portable life support system (PLSS) backpacks they would have worn on the moon.

Lovell also packed his spacesuit's helmet visor assembly (LEVA), his lunar surface gloves and the checklist he would have worn on his wrist.

With everything stowed in lockers and in bags underneath the astronauts' seats, Odyssey was properly weighted for re-entry and the crew safely splashed down in the South Pacific Ocean.

After the flight, and in the 50 years since, Apollo 13's "moon rocks" made their way into museums and private collections. The COAS, Lovell's LEVA, gloves, cuff checklist and the Swigert plaque have been on display at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. One of the armrests is at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, New York, near where the lunar module was built.

The Apollo 13 crew mounted and presented the mirror to Mission Control. The accompanying plaque, which still hangs in Houston, reads, "This mirror flown on Aquarius, LM-7, to the moon April 11-17, 1970, returned by a greatful [sic] Apollo 13 crew to 'reflect the image' of the people in Mission Control who got us back!"

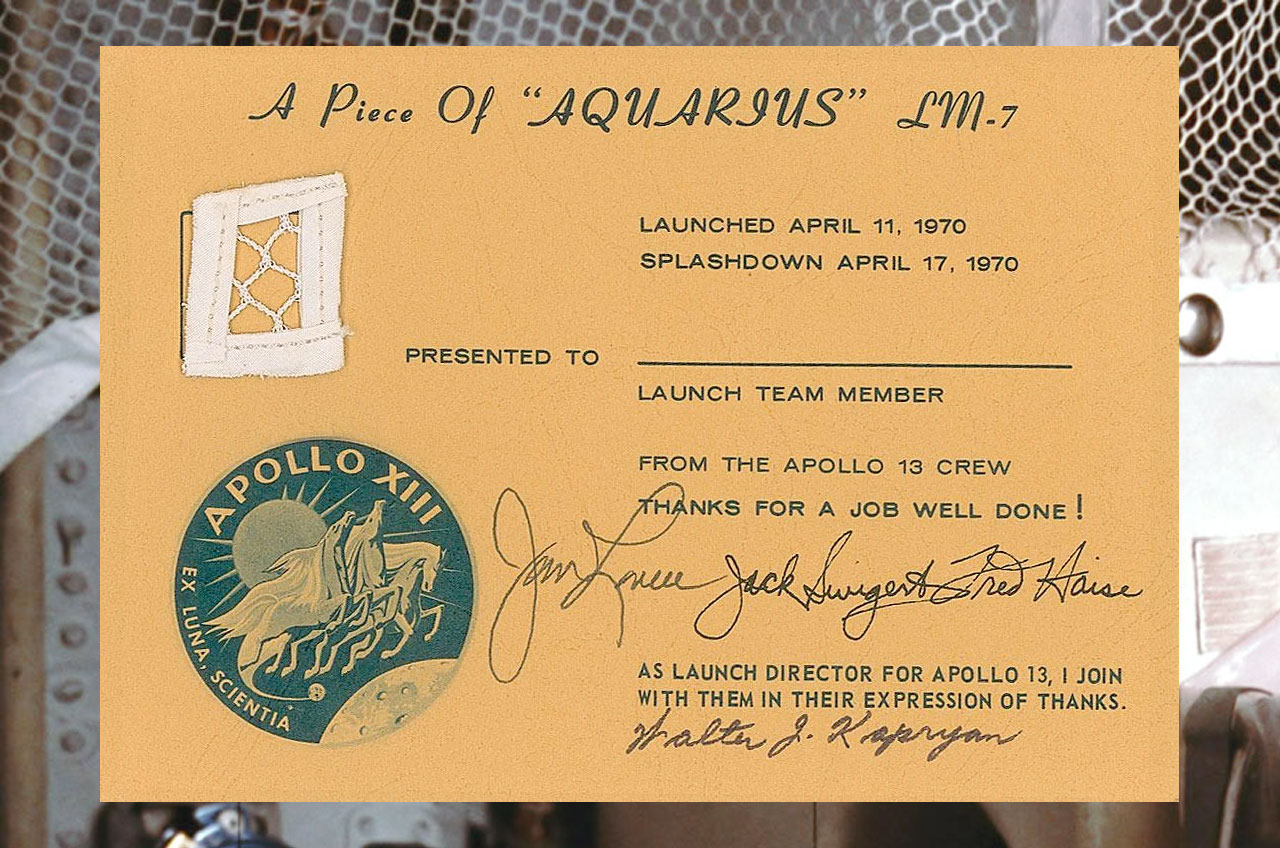

The crew also cut apart the netting that was collected by Haise to present to NASA employees and contractors. These "pieces of Aquarius" serve as souvenirs of their role in the astronauts' safe return.

- Apollo 13 timeline: The hectic days of NASA's 'successful failure' to the moon

- NASA fed Apollo 11 moon rocks to cockroaches (then things got even weirder)

- NASA needs fresh moon rocks. This sample-return mission could get them.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2020 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.