Losing Arecibo's giant dish leaves humans more vulnerable to space rocks, scientists say

Arecibo was a cornerstone in the campaign to protect Earth from asteroids.

Ignorance may feel like bliss, but preparedness offers better odds of surviving what is to come. And when it comes to planetary defense, ignorance just became a bit more inevitable.

Planetary defense is the art of identifying and mitigating threats to Earth from asteroid impacts. And among its tools is planetary radar, an unusual capability that can give scientists a much better look at a nearby object. Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico was one of only a couple such systems on the planet, and that instrument's long tenure is over now after two failed cables made the telescope so unstable that there was no way to even evaluate its status without risking workers' lives, according to the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), which owns the site. Instead, it will be decommissioned.

And when it comes to planetary defense, there's nothing like it.

"There's been statements in the media that, 'Oh we have other systems that can kind of replace what Arecibo is doing,' and I don't think that's true," Anne Virkki, who leads the planetary radar team at Arecibo Observatory, told Space.com. "It's not obsolete and it's not easily replaceable by other existing facilities and instruments."

Related: Losing Arecibo Observatory would create a hole that can't be filled, scientists say

Planetary defense begins with spotting as many near-Earth asteroids as possible — nearly 25,000 to date, according to NASA — and estimating their sizes and their orbits around the sun. Arecibo never played a role in discovering asteroids; that task is much more easily completed by a host of telescopes that see large swaths of the sky in visible and infrared light and are able to catch the sudden appearance of a bright, fast-moving dot between the stars, telescopes like the PanSTARRS observatory in Hawaii. With those first observations, the smallest asteroids and those that stay far from Earth can be safely labeled and more or less forgotten.

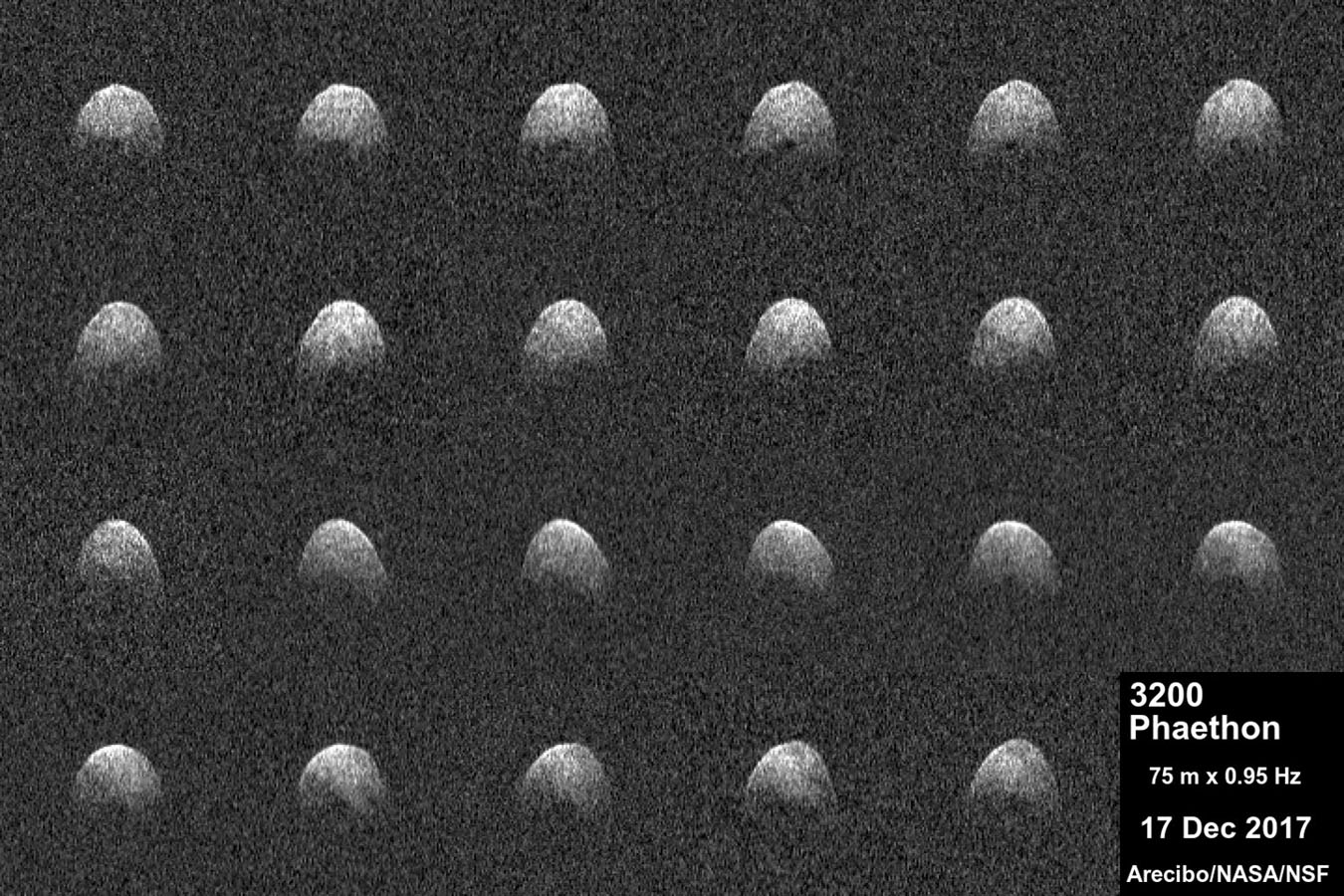

But larger asteroids with orbits that might bring them too close for comfort get additional study, and often, that work has been Arecibo Observatory's. The facility sported a powerful radar transmitter that could bounce a beam of light off an object in Earth's neighborhood. Then, the observatory's massive radio dish could catch the echo of that signal, letting scientists decipher precise details about an asteroid's location, size, shape and surface.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The same telescopes that identify asteroids in the first place can also give scientists the data they need to track a space rock's orbit, but when planetary radar can spot the object, it completes the same work more quickly.

Sometimes that speed will matter, said Bruce Betts, chief scientist at the Planetary Society, a nonprofit space-exploration advocacy group that includes planetary defense among its key issues. "You want to define an orbit as quickly as you can to figure out whether the asteroid is going to hit Earth," Betts told Space.com.

That's because with enough warning, humans could theoretically do something to prevent the collision — likely by nudging the asteroid off track or by breaking it into smaller pieces that wouldn't wreak as much havoc at Earth's surface as a single larger object.

"This is actually a preventable natural disaster if we work hard enough," Betts said. "Even though it's rare, it's something we can actually do something about, unlike say hurricanes or earthquakes in terms of the prevention aspect."

And radar can more quickly offer other details about a space rock that can inform planetary defense, including such vital information as whether an asteroid is actually a single object or a pair of objects in disguise, as 15% of near-Earth asteroids turn out to be, Betts said. "If you needed to deflect it, obviously, it's crucial to know whether there's one or two objects."

Same with the composition of the space rock. "Some are solid metal, some are fluff balls or rubble piles, so they vary considerably in density," Betts said. "If you actually have to deflect an asteroid, if it actually is targeting Earth, the techniques may respond differently depending on whether you're dealing with a very dense asteroid or a very fluffy asteroid."

So radar is a valuable skill for a planet to have.

Arecibo wasn't the only radar facility, but it's a rare capacity given how expensive the technology involved is. With its demise, the only remaining radar transmitter is at the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Center in California, run by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. But this facility has a host of additional responsibilities — it's part of the Deep Space Network that manages communication with spacecraft throughout the solar system and it has military responsibilities as well.

"They are not going to be as flexible with scheduling these recently discovered target observations as Arecibo has been," Virkki said. "If you don't get to observe those targets when they are in the window, then you might lose the opportunity very quickly, and then you have these asteroids that have higher uncertainties in their orbits." And that uncertainty could be the difference between worrying a space rock will hit Earth and being confident it won't.

Goldstone's radar system is also about 20 times less sensitive than Arecibo's was, and the two systems could see different subsets of space, she said. "So it's not exactly going to be replacing Arecibo."

Virkki said there are plans in the works to add radar capability at the Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia, but here again, it won't be able to take over Arecibo's work. Green Bank will use a slightly different flavor of radar than Arecibo did and will be more vulnerable to weather, she said.

And it will have a narrow beam, making it a bit more persnickety in tracking down asteroids. "If you have a very narrow beam, you have to have a very good idea of where you are pointing your radar," Virkki said. "You can't go, like, looking around with that narrow beam." Arecibo was more forgiving when the asteroids' orbits weren't as certain.

Those factors combine to make Arecibo's loss a major blow to the planetary defense capability, according to Ed Lu, a former NASA astronaut and executive director of the B612 Asteroid Institute, a nonprofit organization focused on asteroid science and deflection studies. "This is a big loss to the community," he said. "It's not like we won't have this capability, but it's certainly going to be reduced."

And then, of course, there's the risk that something else will go wrong. "Radars are, of course, complicated and things break," Betts said. "You now don't have any redundancy in your system, it's a single-point failure with the Goldstone radar. So if it breaks at the wrong time, you don't get what you need."

The weakness is coming at a tricky time for planetary defense experts, Lu said. New asteroids are being identified ever more quickly — a few thousand a year, these days — and that trend will only accelerate when the Vera Rubin Observatory begins work within the next year, he said.

"It's going to discover nearly a factor of 10 more asteroids than all other telescopes combined," Lu said of the Rubin Observatory. "What we're actually going to have is quite a large number of new asteroid observations, and within that data set, there are going to be asteroids that are known to be coming very close to the Earth, and which we initially will not be able to rule out as either hitting or not hitting."

The risk of an impact is always the same, of course, but increasing our search capacity while losing characterization capacity is a recipe for greater uncertainty.

There's no easy way to replace the radar capacity that is being lost with Arecibo, all three experts said.

"Obviously, we'd be in favor of finding a way to either repair it, rebuild it, whatever that happens to be, update it," Lu said. "That is a question of money."

"But sometimes, sometimes, if you don't make the investment, you're sorry about it later."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.