SETI tracks distorted signals from distant pulsars with data from destroyed Arecibo Observatory

"Even years after the Arecibo Observatory's collapse, its data continues to unlock critical information that can advance our understanding of the galaxy."

You can knock a good telescope out, but you can't keep it down. Using data from the now-destroyed Arecibo radio telescope, scientists from the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute have unlocked the secrets of signals from "cosmic lighthouses" powered by dead stars.

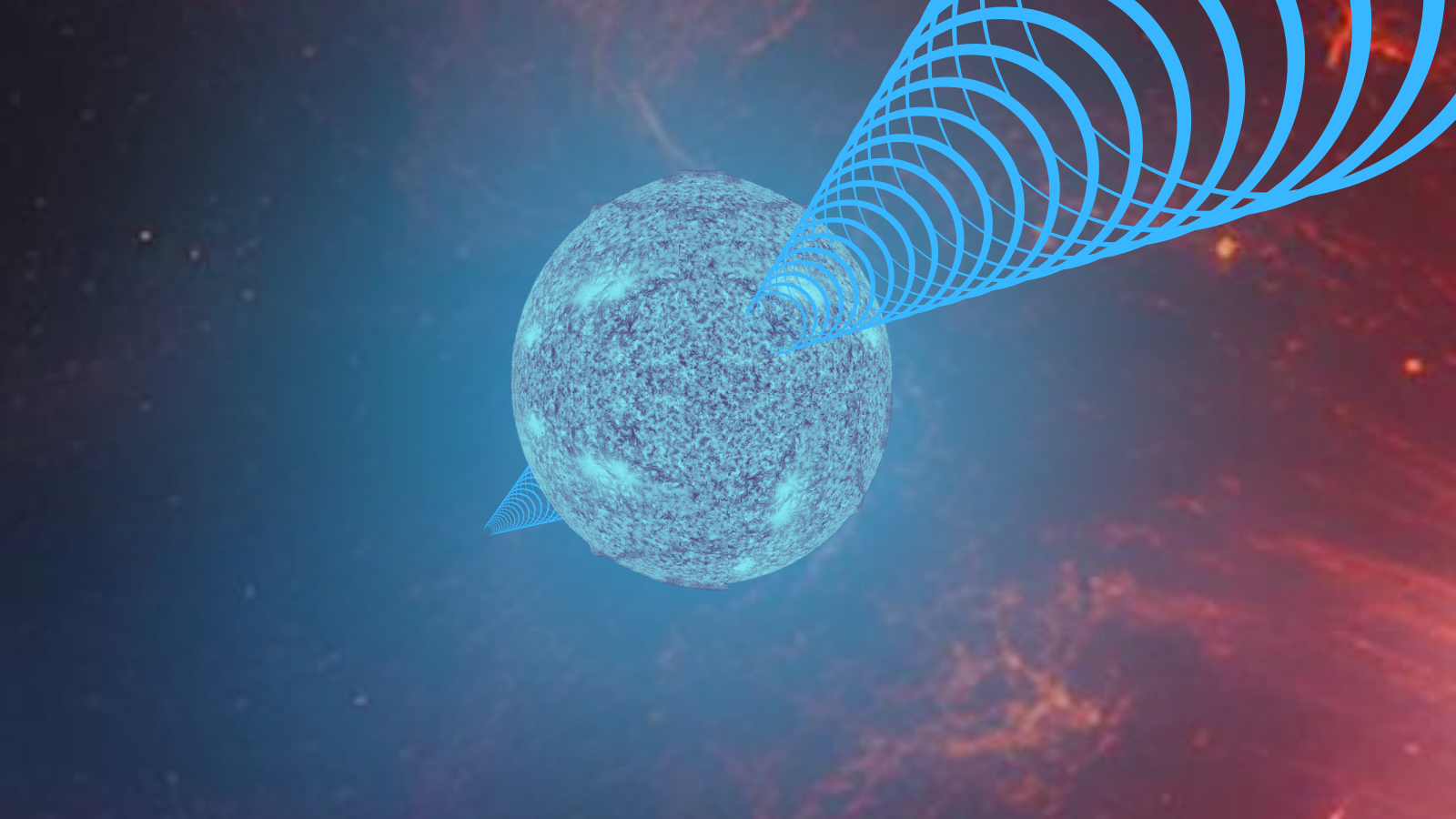

In particular, the team led by Sofia Sheikh from the SETI Institute was interested in how the signals from pulsars distort as they travel through space. Pulsars are dense stellar remnants called neutron stars that blast out beams of radiation that sweep across the cosmos as they spin. To study how these stars' signals are distorted in space, the team turned to archival data from Arecibo, a 1,000-foot (305-meter) wide suspended radio dish that collapsed on Dec. 1, 2020, after the cables supporting it snapped, punching holes in the dish.

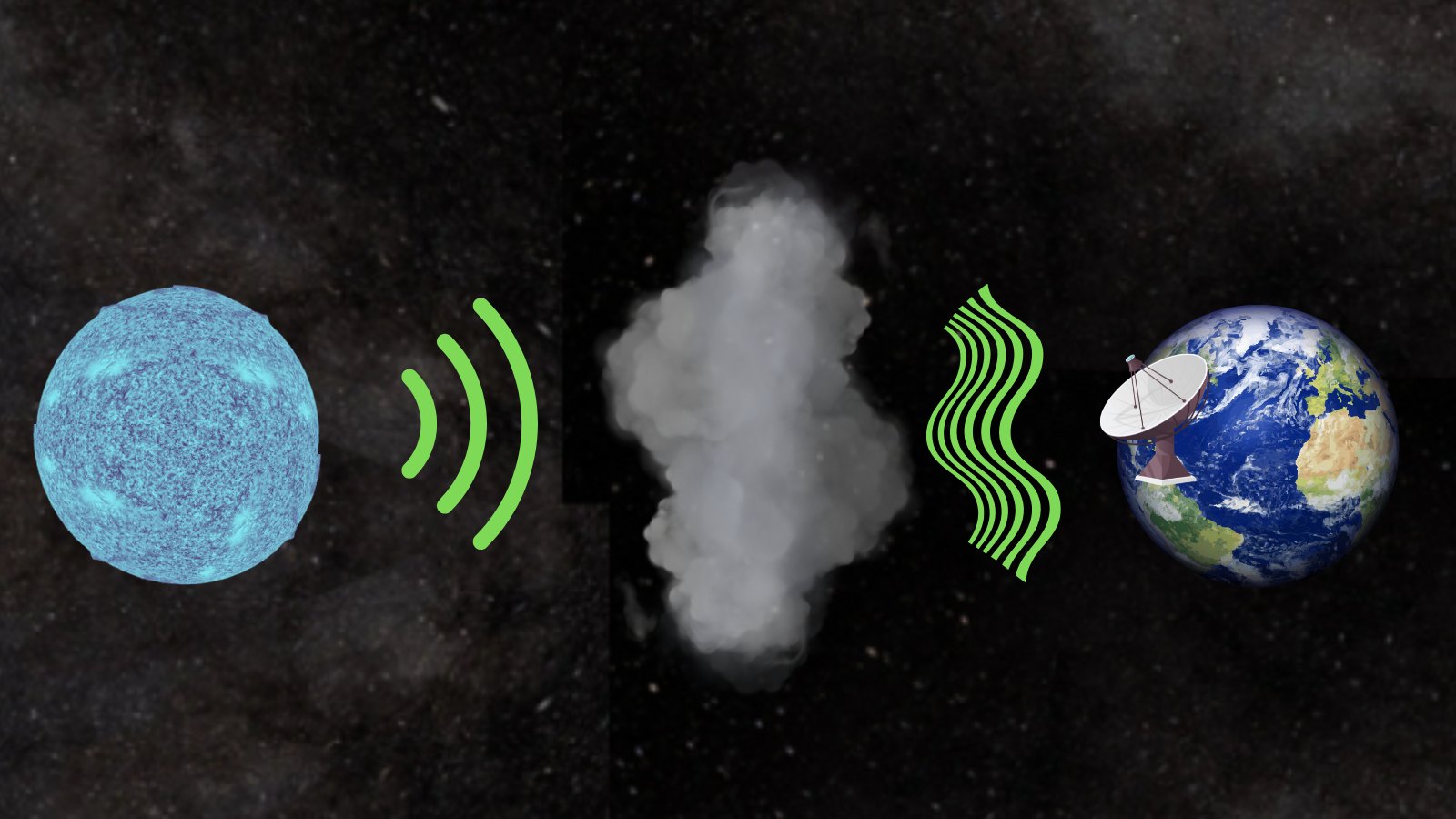

The researchers investigated 23 pulsars, including 6 which had not been studied before. This data revealed patterns in pulsar signals showing how they were impacted by the passage through gas and dust that exists between stars, the so-called "interstellar medium."

When the cores of massive stars rapidly collapse to create neutron stars, they can create pulsars capable of spinning as fast as 700 times every second thanks to the conservation of angular momentum.

When pulsars were first discovered in 1967 by Jocelyn Bell Burnell, some proposed the frequent and highly regular periodic pulsing of these remnants to be signals from intelligent life everywhere in the cosmos. Just because we now know that isn't the case doesn't mean SETI has lost interest in pulsars!

The radio wave distortions the team was interested in are known as diffractive interstellar scintillation (DISS). DISS is somewhat analogous to the patterns of rippling shadows seen at the bottom of a pool as light passes through the water above.

Instead of ripples in water, DISS is caused by charged particles in the interstellar medium that create distortions in radio wave signals traveling from pulsars to radio telescopes on Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team's investigation revealed that the bandwidths of pulsar signals were wider than current models of the universe suggest should be the case. This further implied that current models of the interstellar medium may need to be revised.

The researchers found that when galactic structures such as the spiral arms of the Milky Way were accounted for, the DISS data was better explained. This suggests that challenges in modeling the structure of our galaxy should be faced in order to continually update galactic structure models.

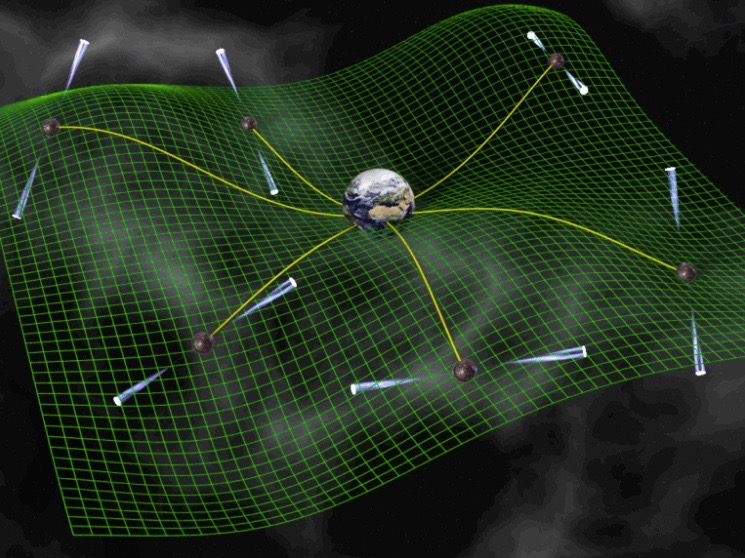

Understanding how signals from pulsars work is important to scientists because, when considered in large arrays, the ultraprecise periodic signals from pulsars can be used as a timing mechanism.

Astronomers use these "pulsar timing arrays" to measure the tiny distortions in space and time caused by the passage of gravitational waves. A recent example is the use of the NANOGrav pulsar array to detect the faint signal from the gravitational wave background.

This background hum of gravitational waves is believed to be the result of supermassive black hole binaries and mergers in the very early universe. A better understanding of DISS could help refine the detection of gravitational waves by projects like NANOGrav.

"This work demonstrates the value of large, archived datasets," Sheikh said in a statement. "Even years after the Arecibo Observatory's collapse, its data continues to unlock critical information that can advance our understanding of the galaxy and enhance our ability to study phenomena like gravitational waves."

The team's research was published on Nov. 26 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.