NASA's daring Artemis 1 'Red Crew' saved the day for the launch to the moon. Here's how.

Not all space heroes wear spacesuits.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — Not all space heroes wear spacesuits. Sometimes they wear hard hats.

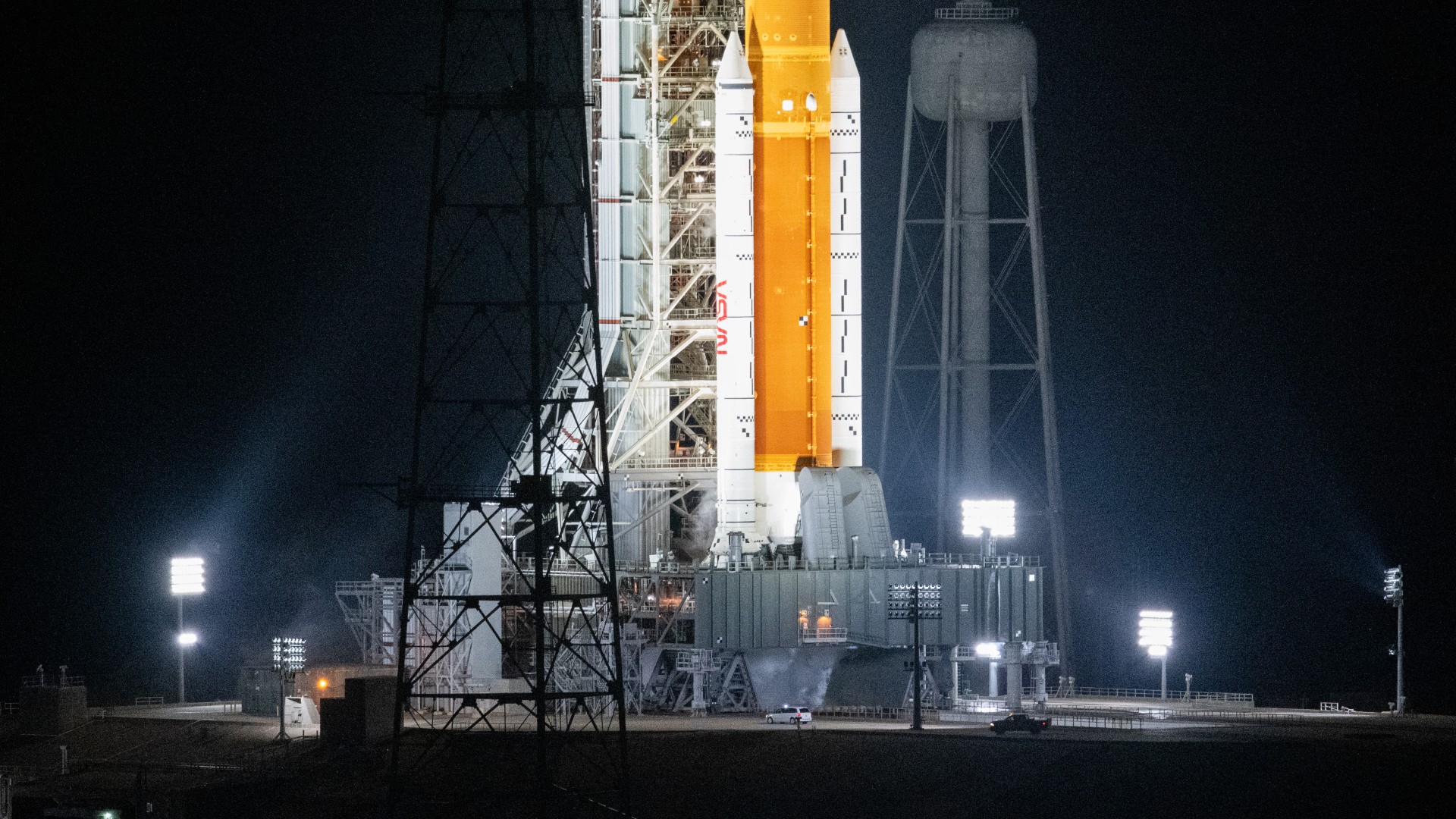

NASA's $4.1 billion Space Launch System (SLS) rocket sat waiting on Launch Pad 39B here at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Tuesday (Nov. 15) ahead of launch when sensors detected yet another fueling leak. Such leaks were the bane of this rocket's existence during previous launch attempts, and when another leak arose during this countdown, it seemed to many that we would witness yet another scrubbed launch — or worse, a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building for repairs.

Yet that's not what happened, as the spectacle in the Florida skies early on Wednesday morning (Nov. 16) proved. As the world watched to see if this fuel leak could be repaired, Artemis 1 mission managers made a risky decision: They would send a "Red Crew," a specialized team of technicians, to what engineers call "zero deck" at the base of the fueled rocket to try to stop the liquid hydrogen leak.

Luckily, the Red Crew was successful.

Related: NASA launches Artemis 1 moon mission on its most powerful rocket ever

Live updates: NASA's Artemis 1 moon mission

The unsung heroes were able to pull off the daring repair, and just hours later Artemis 1 was on its way to orbit around the moon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

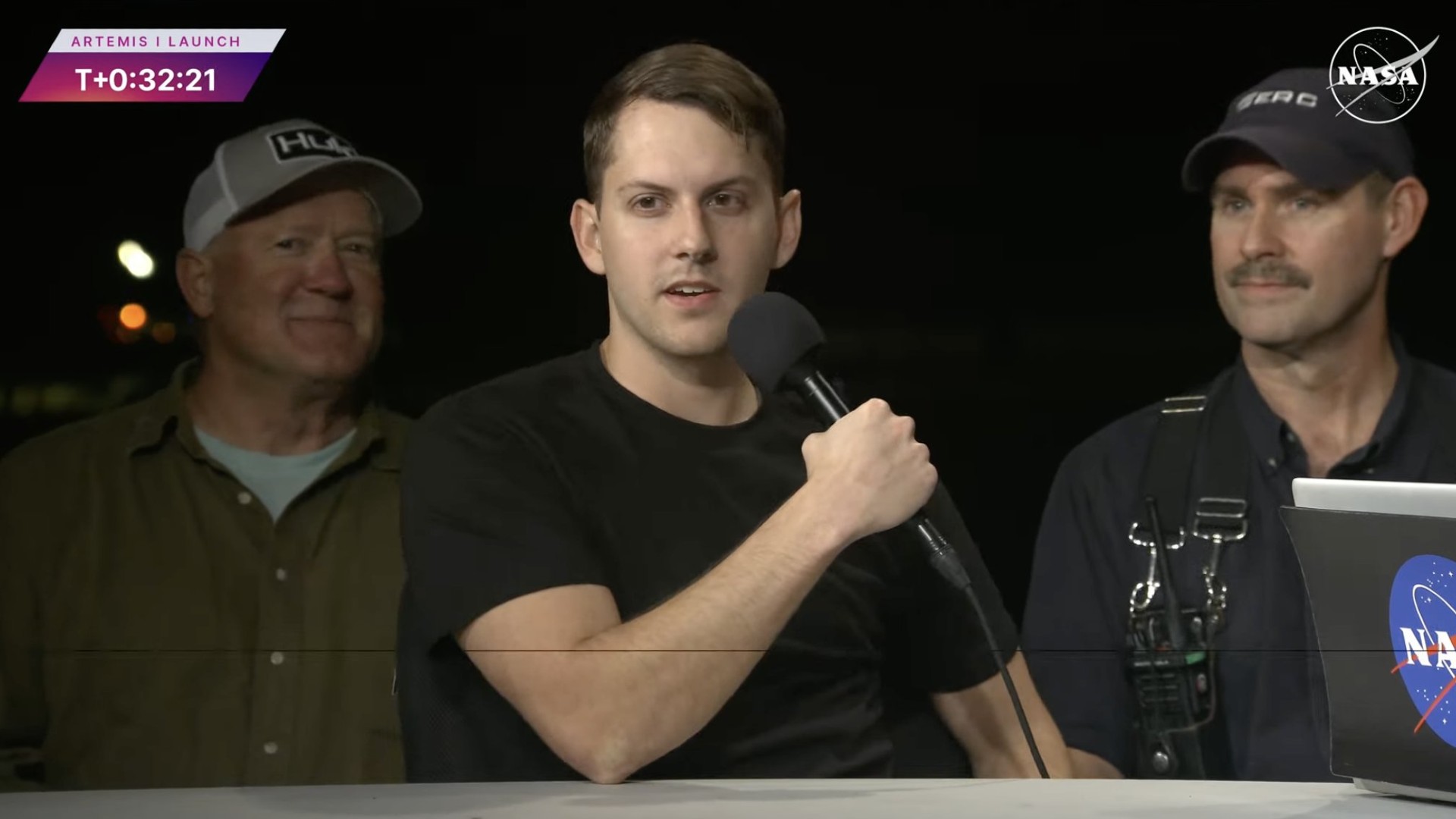

Trent Annis, one of the Red Crew members, said that although it was terrifying being beneath the fueled rocket, his team remained focused on the job at hand.

"I'd say we were very focused on what was happening up there," Annis told NASA TV after the launch. "Just making sure we knew what was happening. Because the rocket is, you know, it's alive, it's creaking, it's making venting noises, it's — it's pretty scary. So on zero deck, my heart was pumping. My nerves were going but yeah, we showed up today."

Annis and the other two members of the crew, Billy Cairns and Chad Garrett, were sent to the mobile launch platform at the base of SLS to tighten down "packing nuts," hardware that helps form a tight seal on the replenishment valves through which liquid hydrogen was pumped into the Artemis 1 moon rocket's core stage after the main tanking procedure. Because hydrogen is such a small molecule, it manages to find its way out of even the tightest seals, meaning NASA has to keep replenishing the hydrogen fuel tanks throughout the launch countdown even after main fueling procedures have been completed.

With Artemis 1's launch window ticking away on Tuesday night (Nov. 15), Cairns, Garrett and Annis arrived at the mobile launch platform underneath the highly dangerous SLS vehicle at 10:12 p.m. EST (0312 GMT on Nov. 16) to stop the leak — and fast — or risk losing this launch opportunity. Once at the platform, the crew discovered that the packing nuts were "visibly loose," according to a statement by launch commentator Derrol Nail on NASA TV's media channel.

Luckily, with nerves seemingly made of steel, the Red Crew performed admirably, tightening the nuts and enabling the Artemis 1 launch countdown to resume.

"You know, I still can't believe it. Like I said it's really just amazing," Annis said during the post-launch interview.

"We had a lot of people here helping us out, a lot of teams, the fire room," Annis said. "I'm sure that was hectic. And you know, NASA, Boeing, all the other companies did a great job. We're glad to be part of that." In a testament to how rare the dangerous procedure was, NASA TV commentators interviewing the Red Crew added that Cairns said he has served on the crew for 37 years and had never before been called in for a repair on a fully-fueled rocket before last night's daring excursion.

The Artemis 1 mission is now safely on its 25-day mission through deep space toward the moon, where it will pave the way for future crewed missions. The Orion spacecraft will reach the moon on Monday (Nov. 21) before spending several more days positioning into lunar orbit.

The mission will conclude on Dec. 11 when Orion will reenter Earth's atmosphere at 25,000 mph (40,233 kph) and experience temperatures up to 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 Celsius) before splashing down in the Pacific Ocean — hopefully with no Red Crew needed.

Follow Brett on Twitter at @bretttingley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Brett is curious about emerging aerospace technologies, alternative launch concepts, military space developments and uncrewed aircraft systems. Brett's work has appeared on Scientific American, The War Zone, Popular Science, the History Channel, Science Discovery and more. Brett has English degrees from Clemson University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. In his free time, Brett enjoys skywatching throughout the dark skies of the Appalachian mountains.