How will Artemis 2 astronauts exercise on the way to the moon?

Like boxers in training, they will use a flywheel.

MONTREAL, CANADA — From simulators to space snacks, Artemis 2 astronauts are trying to practice all facets of moon living before they head toward the lunar surface in 2025.

Artemis 2 astronaut Jeremy Hansen emphasized here at Canadian Space Agency (CSA) headquarters that every detail matters when getting ready for the big mission, as it is the first moon excursion since 1972 that will have humans on board.

The constant practice, he told reporters in a gaggle, helps "keep our skills sharp, to challenge ourselves ... we're constantly in an operational environment where you're making decisions."

CSA's Hansen and his three NASA astronaut crewmates are practically living in mockups of their Orion spacecraft to learn how to safely maneuver themselves in tight quarters. And among their tasks to tackle is something mundane, yet essential: learning how to stay fit in a tiny space while floating all the time.

Related: Astronauts won't walk on the moon until 2026 after NASA delays next 2 Artemis missions

While Orion has 60% more room than the Apollo moon capsules of the 1960s and 1970s, it has to carry four astronauts instead of three. Certainly, computers are wearable these days instead of the "single-room" machines of two generations ago — and, NASA knows how to pack efficiently.

Nevertheless, getting anything on board will be a challenge.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We're very mass-constrained and space-constrained, and that does determine how much room we have to bring things," Hansen said, noting his limited personal items will include a single pendant for his wife and three children. Orion only has 316 cubic feet (8.9 cubic meters) of space in it, which is something akin to a tiny bedroom you'd find in urban areas like New York City or Singapore. Add in computers and equipment, and that small space shrinks swiftly.

By these standards, the six-bedroom-house-sized International Space Station seems incredibly roomy. To that end, Orion has no space for any of the large exercise machines the ISS currently holds: a treadmill with straps to hold running astronauts down, a piston-driven weight machine to counteract "weightlessness," and an exercise bicycle. Taken together, the exercise equipment alone would require nearly triple the space of an Orion spacecraft, so new thinking is needed.

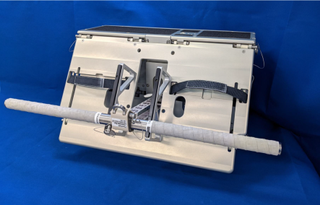

Enter a portable solution: The flywheel.

Versions of the flywheel have been floating around since at least 2016, when the device for astronauts was called ROCKY after the fictional boxer portrayed by Sylvester Stallone in numerous films. (That's Resistive Overload Combined with Kinetic Yo-Yo, if you're looking for some band name inspiration.)

Today's flywheel version is nested below the side hatch on Orion meant for entering and exiting.

In true small space thinking, the device acts as a step when the astronauts come inside during launch day. The crew will spend 30 minutes daily doing squats and deadlifts using cables on the device that act like a yo-yo; simple adjustments also allow the flywheel to act as a rowing machine.

The flywheel is tiny, smaller than a carry-on suitcase airlines typically allow in the passenger cabin. It also has a mass of only about three sacks of potatoes: 30 pounds, or 14 kilograms. But with small size comes a big limitation: the elastic strength maxes out at only 400 pounds (181 kilograms), which is interesting considering similar cables did not work so well for ISS missions.

NASA used to have a weight-lifting machine on the ISS called the Interim Resistive Exercise Device that also used cables that maxed out around 300 pounds (136 kg). Worse, reports from places like Wired indicate exercises like squats were only half as effective in microgravity. The newer Advanced Resistive Exercise Device does away with strength exercises "maxing out" by instead using pistons, helping astronauts stay fitter for 180 days or more in orbit. ARED is a key factor in allowing astronauts to return home with more bone mass than before, peer-reviewed research shows.

Fortunately, however, Orion is rated for shorter missions. The Artemis 2 astronauts should only use the capsule for 10 days, and time in space will go up only to a month on future missions. The fear of "deconditioning" in a floating environment is therefore less in this case, although medical professionals may eventually consider other solutions.

"As the missions get longer, that's one of the things we need to look at: what is the minimum amount of exercise that you need to perform to maintain a certain level of fitness?" said Natalie Hirsch, CSA's project manager of operational space medicine, during a media gaggle and demonstration of flywheel.

Hirsch noted astronaut health is not the only thing to think about. As any lab manager knows, vibrations can induce unexpected effects in experiments or in equipment. Orion engineers have never tested exercise equipment in space, given that Artemis 1 flew uncrewed around the moon in 2022 and the spacecraft just had a brief Earth-orbiting mission without astronauts in 2014.

Astronaut exercise data on Artemis 2, Hirsch said, will help fortify the spacecraft design against risky vibrations ahead of more ambitious moon-landing missions later in the decade.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.