Asteroid collisions may be responsible for mysteriously magnetic meteorites on Earth

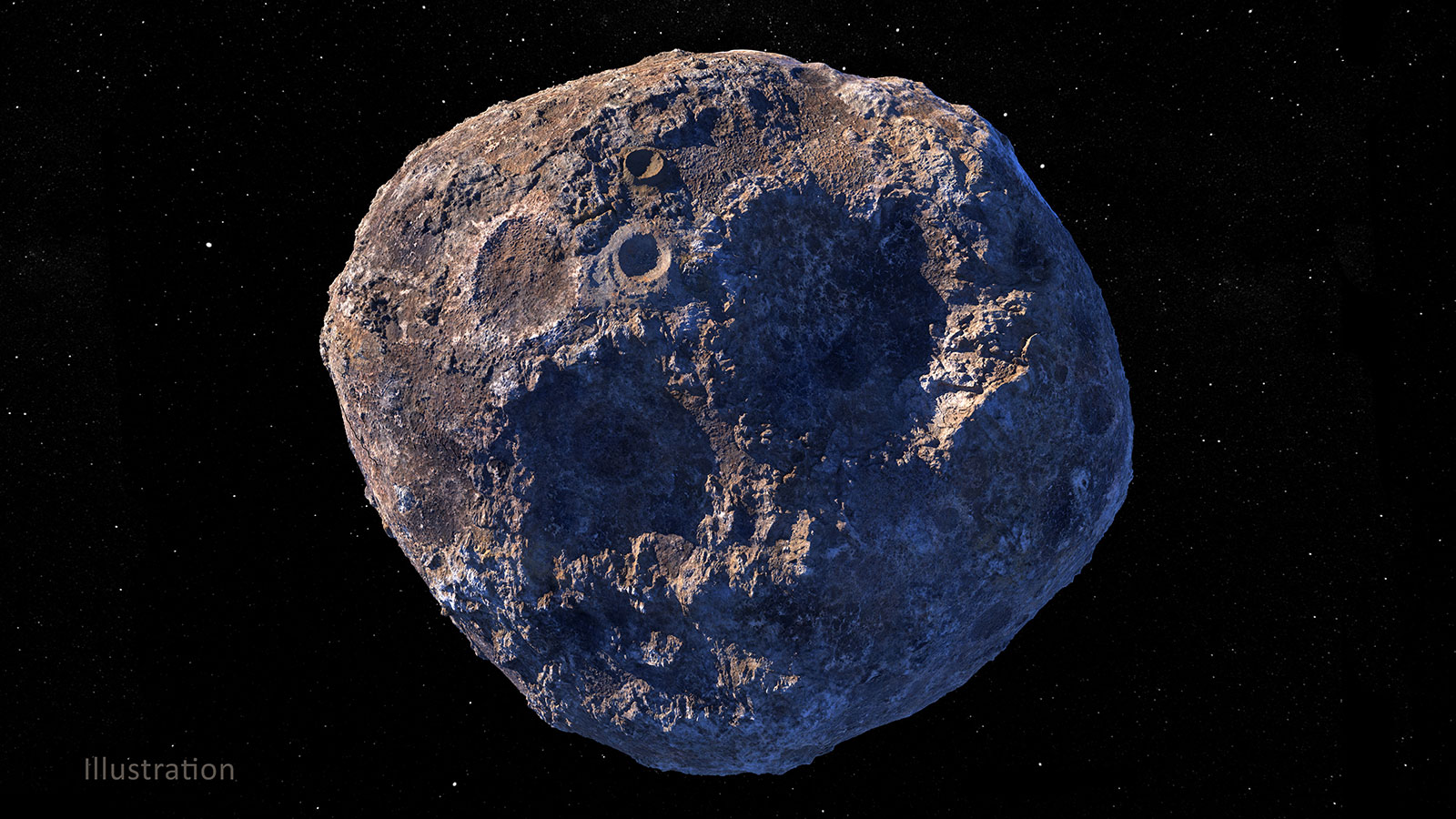

Rubble-pile asteroids form when asteroids collide and their shards reassemble into new, shuffled asteroids. And when they do, according to a new study, they might give the renewed asteroid a temporary magnetic field.

This result might address a mystery that has baffled astronomers for years: Some metallic meteorites hold traces of magnetism as if they carry remnants of internal magnetic fields. That shouldn’t be possible. Even if a meteorite does contain iron, it isn't expected to have a circulating dynamo, like the one in Earth's inner core, which scientists think is necessary to generate a magnetic field.

"I had been aware of this puzzle for some time," Zhongtian Zhang, a planetary scientist at Yale University, said in a statement.

And as he studied rubble-pile asteroids, the puzzle returned to his mind. So, Zhang and fellow Yale planetary scientist David Bercovici turned to modeling asteroid collisions.

Related: Boomerang meteorite may be the 1st space rock to leave Earth and return

When two iron-rich asteroids smashed into each other and scattered into shards, they discovered, some of those shards would coalesce into a chillier inner core that was coated by a warmer layer of molten rock. Then, if the shards were just the right size, the cold core would start stripping elements, such as sulfur, from the hot liquid.

This model illustrated that the resulting heat transfer could create circulation sufficient to trigger a dynamo and, thus, a magnetic field. And if such a dynamo formed, it could last for millions of years — and its traces would be detectable by astronomers long afterward.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The study was published on July 31 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.