'Twilight telescopes' are finding 'city-killer' asteroids in an unexplored region of our solar system

When it comes to looking for asteroids, we have a blind spot. It may seem counterintuitive, but the most important asteroid discoveries are now being made in twilight, when astronomers are able to look close to the horizon — and close to the sun — for little-known asteroids that orbit inside the orbits of Earth, Venus and even Mercury.

In a perspective published in Science today, asteroid-hunter Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution of Science highlights the new "twilight telescope" surveys and the riches they're beginning to discover. That includes the first asteroid with an orbit interior to Venus and one with the shortest-known orbital period around the sun, both of which have been unearthed in the last two years. It also includes "city-killers," asteroids large enough that if they were to impact Earth, the damage would be severe.

"We're doing a full-fledged survey looking for anything that moves around the orbit of Venus, which is somewhere we haven't really surveyed very deep in the past with anything other than small one meter telescopes," Sheppard, who runs a twilight survey using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile, told Space.com. "It's pretty hard to do and generally the larger telescopes don't have a very big field of view so you can't cover a lot of sky."

However, DECam and another telescope are making it much easier to probe a previously hidden world of asteroids that until now have been obscured by the sun's glare.

Related: Just how many threatening asteroids are there? It's complicated.

Why look for asteroids in twilight

About 30 years of methodical searching of the skies have resulted in finding most asteroids 3 miles (5 kilometers) across. Models and surveys suggest that more than 90% of "planet-killer" Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) (those larger than 0.6 miles, or 1 km) have been found, but only about half of the "city-killer" NEOs (those larger than 460 feet, or 140 meters) are known.

So where are the rest? "There are going to be others either close to the sun, so hard to observe, or on aliasing orbits with Earth that makes them hard to find by the normal survey," Sheppard said. Their eccentric orbits make them only visible in twilight skies.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sheppard's team has already identified a mid-sized asteroid, called 2022 AP7, whose orbit crosses that of Earth, matching the criteria of a "potentially hazardous asteroid." But others, in all likelihood, remain to be found. "The main reason we haven't found all the 'city-killers' is simply because we haven't been observing the sky to the same depth over years and years to find them," Sheppard said.

The language of asteroids

Near-Earth asteroids come in a variety of flavors, all designated by characteristics of the space rock's orbit. For example, Amors get close to Earth, but never cross its orbital path around the sun, so pose no danger to us.

Not so for the Apollo asteroids, which cross Earth's orbit, but are mostly beyond it. This category includes the likes of Apophis and Bennu, and these space rocks generally orbit the sun from just beyond Earth's orbital path, which means that wide-field telescope surveys operating at night are best posed to spot these asteroids.

Other categories of near-Earth asteroids are much more difficult to find, like Atens (which cross Earth's orbit and remain mostly within it), Atiras (also called Apohele, which orbit interior to Earth's orbit) and Vatiras (which orbit inside the orbital path of the planet Venus). However, Sheppard's survey — which uses just 10 minutes of telescope time right after sunset and before sunrise to search close to the sun — is turning up some surprises.

The one true 'Venus Girl'

So far astronomers know of only one Vatiras space rock.

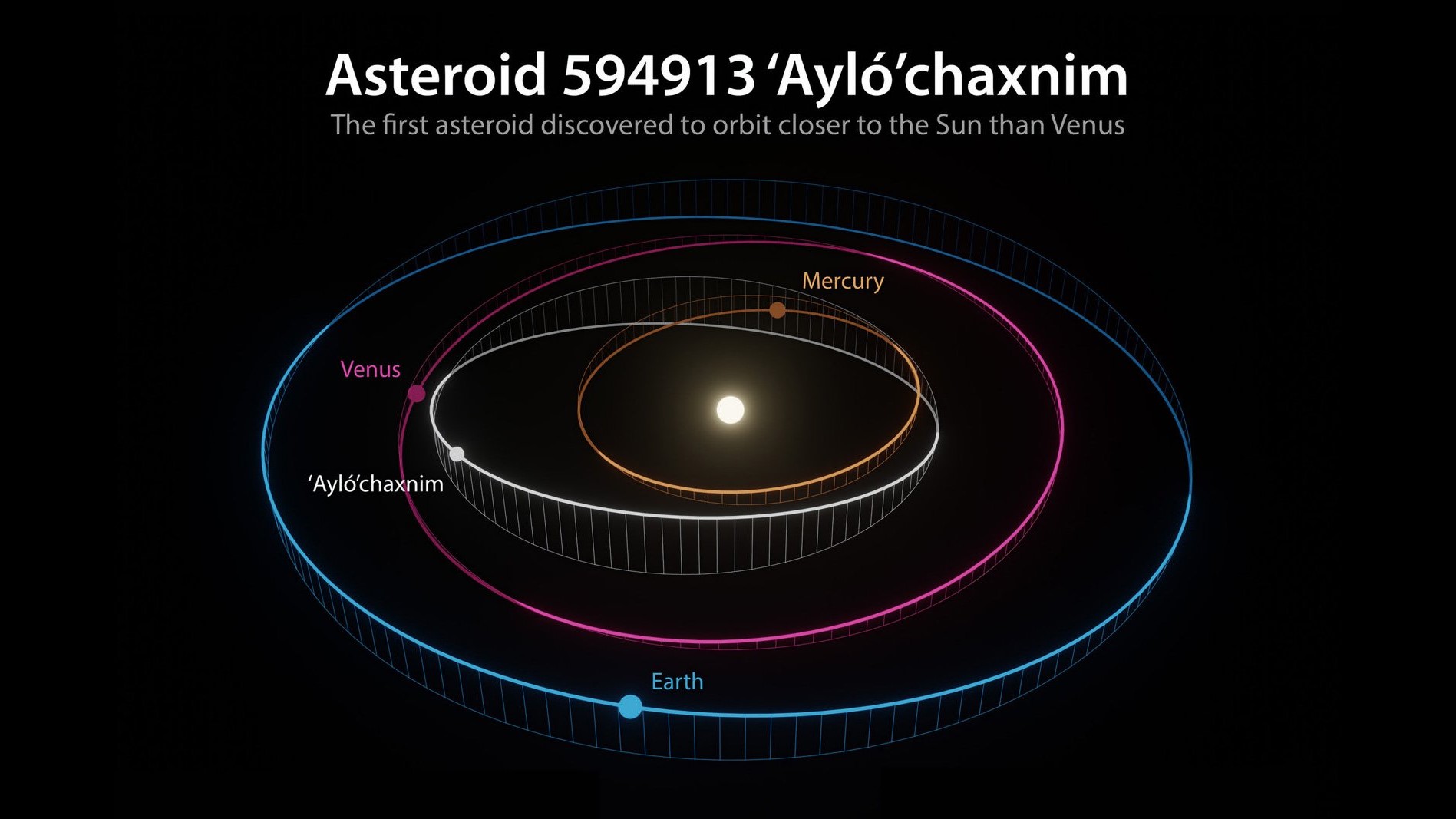

Asteroid 2020 AV2 was discovered on Jan. 4 using the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) telescope at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego, California. The facility is on ancestral lands of the indigenous Pauma group, who were asked to name it. They chose 'Ayló'chaxnim, which means "Venus girl" in their Luiseño language.

The asteroid is between 0.6 miles to 1.9 miles wide (1 to 3 km) across, orbits on a path that's tilted 15 degrees relative to the plane of the solar system, and takes 151 days to circle the sun. Scientists suspect the asteroid was probably thrown into Venus' orbit after a close encounter with another planet.

The sun's nearest neighbor

In the twilight hours of Aug. 13, 2021, Sheppard discovered an asteroid with the shortest orbital period yet. Caught in data from the DECam, asteroid 2021 PH27 is about 0.6 miles across and its surface probably heats up to about 930 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius) — hot enough to melt lead — because its 113-day orbit carries it as close as 12 million miles (20 million km) from the sun. Only Mercury has a shorter orbit of the sun, at 88 days. However, since its orbit crosses both the orbits of Mercury and Venus, this asteroid classed as an Atira.

2021 PH27 could be an extinct comet, scientists think, given that its orbit is inclined from the main plane of the solar system by 32 degrees. That tilt suggests that the object may be from the outer solar system, sent into a closer orbit around the sun after passing near one of the terrestrial planets.

The top 'twilight telescopes'

ZTF and DECam are where it's at when looking for asteroids that orbit interior to Venus.

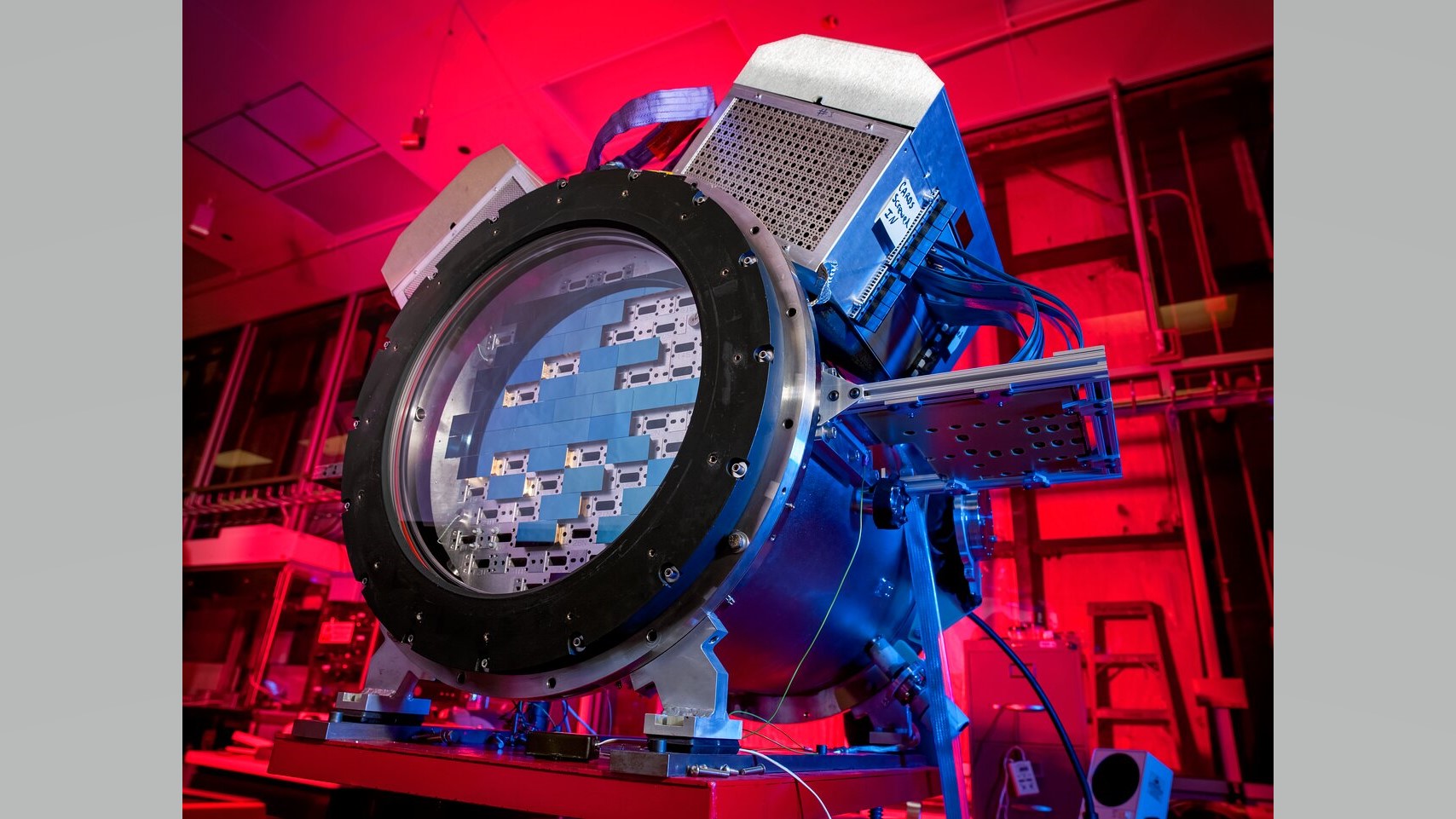

You might think that the bigger the telescope, the better for asteroid-hunting, but larger telescopes have smaller fields of view. ZTF, which rapidly scans the sky, has so far spotted one Vatira and several Atira asteroids. DECam, a 570-megapixel CCD imager designed for the Dark Energy Survey (DES) has found a few Atira asteroids, including 2021 PH27. ZTF has a bigger field of view, but DECam can spot objects much fainter in brightness as measured by magnitude.

"DECam changes everything," Sheppard said. "We're now going over a magnitude deeper than people have gone to before — we're opening up a whole new area of space that we're able to constantly monitor that hasn't really been monitored well in the past."

Expect to hear a lot more about new asteroids being discovered in an unexplored region of our solar system.

Jamie Carter is the author of "A Stargazing Program For Beginners" (Springer, 2015) and he edits WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com. Follow him on Twitter @jamieacarter. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jamie is an experienced science, technology and travel journalist and stargazer who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com and author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, and is a senior contributor at Forbes. His special skill is turning tech-babble into plain English.