Asteroid impacts may have helped make Mars a more life-friendly place — and not just by delivering water and the carbon-based building blocks of life as we know it to the Red Planet.

Incoming space rocks may also have helped seed Mars with biologically usable forms of nitrogen long ago, if the planet's atmosphere were rich in hydrogen (H2) back then, a new study reports.

In 2015, NASA's Mars rover Curiosity discovered nitrate (NO3) in the rocks of Gale Crater, the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) hole in the ground the six-wheeled robot has been exploring since 2012. Nitrate is a "fixed" form of nitrogen; life-forms, at least as we know them on Earth, can nab NO3's nitrogen and incorporate it into biomolecules like amino acids. That's in contrast with "unfixed" gaseous nitrogen (N2), which features two tightly bonded, inert and relatively inaccessible nitrogen atoms. (This inaccessibility helps explain why farmers fertilize their fields, even though Earth's air is nearly 80 percent N2.)

Related: The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)

Scientists aren't sure where the Gale Crater nitrate came from — and that's where the new study comes in.

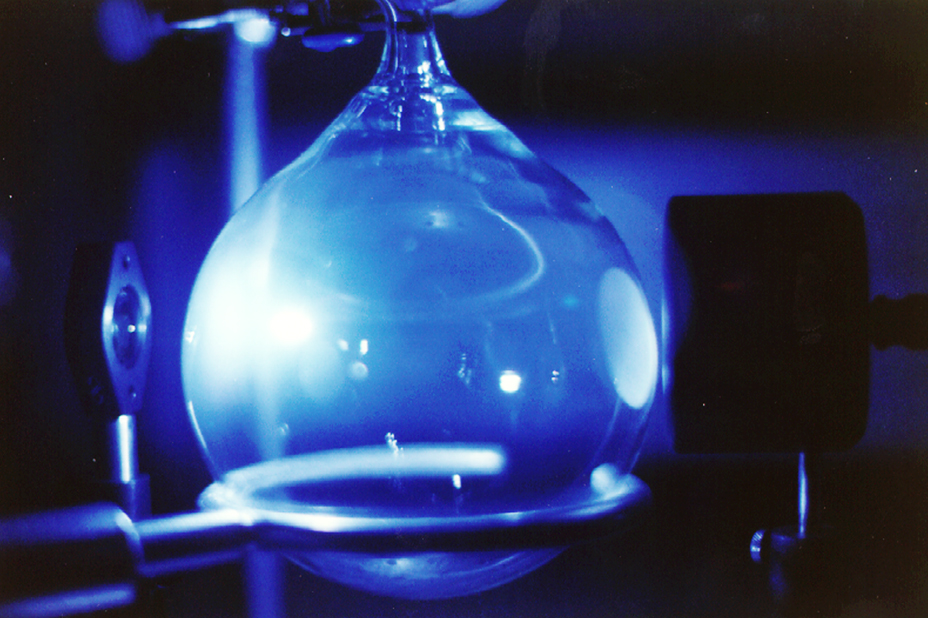

A team of researchers simulated the early Martian atmosphere by filling flasks with various mixtures of hydrogen, nitrogen and carbon dioxide gases. The scientists blasted the flasks with pulses of infrared light, to mimic the shockwaves created by asteroids plowing into the Red Planet's air, and then measured how much nitrate was formed.

"The big surprise was that the yield of nitrate increased when hydrogen was included in the laser-shocked experiments that simulated asteroid impacts," study leader Rafael Navarro-González, of the Institute of Nuclear Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, said in a statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This was counterintuitive, as hydrogen leads to an oxygen-deficient environment while the formation of nitrate requires oxygen," he added. "However, the presence of hydrogen led to a faster cooling of the shock-heated gas, trapping nitric oxide, the precursor of nitrate, at elevated temperatures where its yield was higher."

Mars' current atmosphere is just 1 percent as thick as that of Earth. But the Red Planet's air was much thicker about 4 billion years ago, and ancient Mars featured oceans and long-lived lake-and-stream systems as a result.

The composition of that long-lost atmosphere is not well understood. But some modeling work suggests that H2 may have been present in substantial amounts, helping keep the Red Planet warm enough to support all that liquid water.

"Having more hydrogen as a greenhouse gas in the atmosphere is interesting both for the sake of the climate history of Mars and for habitability," study co-author Jennifer Stern, a planetary geochemist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in the same statement.

"If you have a link between two things that are good for habitability — a potentially warmer climate with liquid water on the surface and an increase in the production of nitrates, which are necessary for life — it's very exciting," she added. "The results of this study suggest that these two things, which are important for life, fit together and one enhances the presence of the other."

The study was published in January in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

- Mars Myths & Misconceptions: Quiz

- Life on Mars: Exploration & Evidence

- Amazing Mars Photos by NASA's Curiosity Rover (Latest Images)

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.