Astronauts become archaeologists to document space station 'dig sites'

In a recent scene familiar to many, even those not well-versed in the discipline, a researcher marked off square areas in order to catalog the layers of contents buried within. These "test pits," which were similar to the squares made at the sites of ancient cities and bygone civilizations, were based on a basic technique practiced by archaeologists.

Only this time, the researcher was an astronaut and the "dig sites" were on board the International Space Station (ISS).

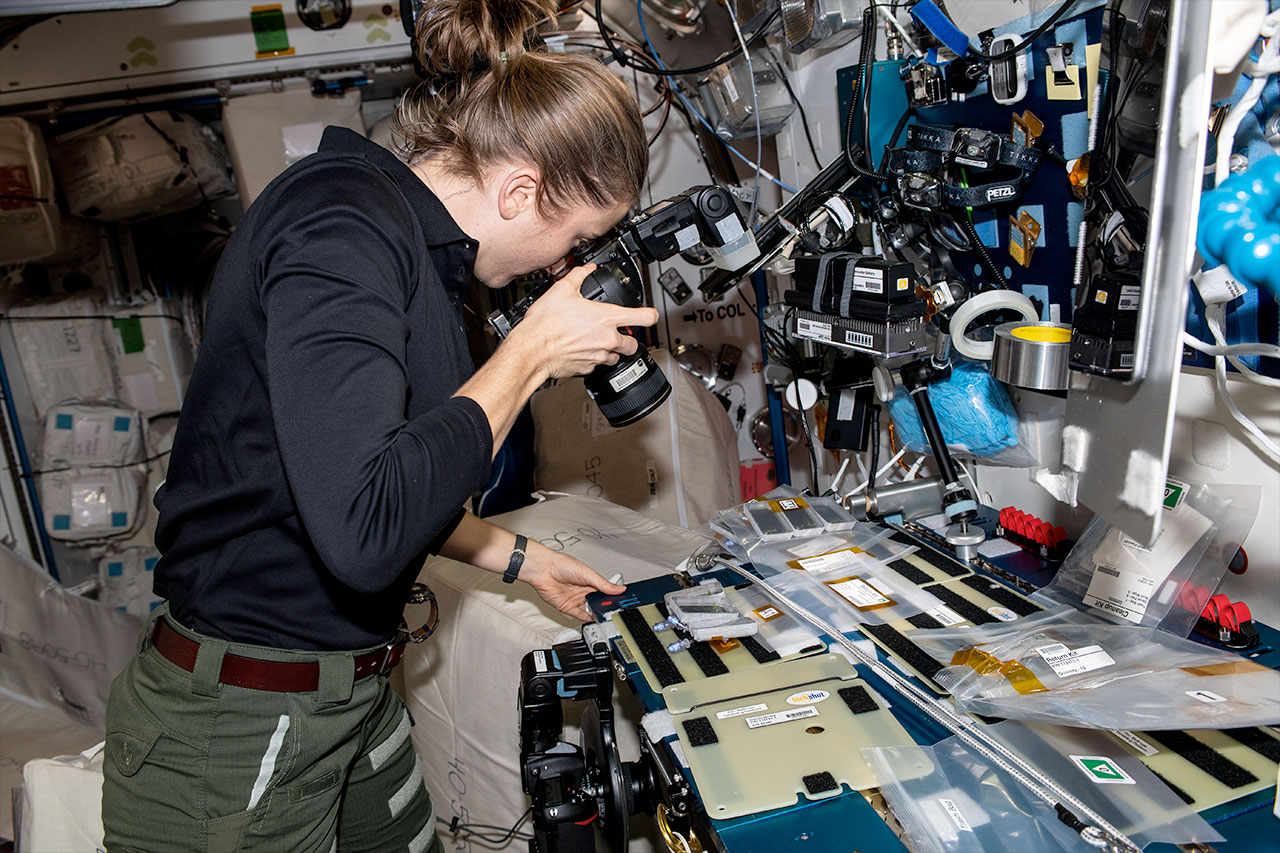

"We are extremely excited and proud to announce that the first archaeological study ever performed outside the Earth began today," the team behind SQuARE, or Sampling Quadrangle Assemblages Research Experiment, wrote in a blog entry on Jan. 14. "NASA astronaut Kayla Barron set up an experiment consisting of six sample areas in as many modules that will be documented by the crew for us every day for the next 60 days."

Related: International Space Station at 20: A photo tour

That same day, NASA noted SQuARE getting underway in its daily summary of activities aboard the space station.

"SQuARE is an investigation that aims to document items within six defined locations around the ISS over time," the space agency wrote. "The idea is to look at the ISS as an archaeological site, and each of the squares as a 'test pit.'"

Social science in space

Barron, a flight engineer on the Expedition 66 crew, used Kapton polyamide tape — a common adhesive used on the orbiting complex — to mark off the corners of 1-meter (39-inch) squares in five areas chosen by the International Space Station Archaeological Project. The selected sites included the galley table in Node 1 ("Unity"); the starboard workstation in Node 2 ("Harmony"); two science racks, one each on the forward walls of both the Japanese "Kibo" and European "Columbus" modules; and the wall across from the WHC (the waste and hygiene compartment, or toilet) in Node 3 ("Tranquility").

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The sixth square, which was placed on the one of the racks on the port side of the U.S. lab module "Destiny," was the crew's choice based on what they considered interesting to document.

Daily photography began the next week, with a ruler and color calibration chart added to each shot for reference. For the first month, the plan was to take photos around the same time every day, followed by a second month at random times, giving the team behind the study a chance to assess which approach was more effective to their needs.

Key to both months of documentation was that the astronauts did not do anything to the items inside the squares other than what they would do in their normal day-to-day, regular course of use.

"We have specifically instructed the crew not to move any items," Justin Walsh, co-principal investigator for the International Space Station Archaeological Project and an archeologist whose research has included human activity in space, said in an interview with collectSPACE.com. "We want to capture the moment as it is, not as they might think we would want to see it."

The photographs will be transmitted back to Earth to be analyzed. A team of people, including specialists at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston and at Axiom Space, a commercial space services company, will assist in identifying the objects captured in each square.

Microgravity migrations

Archaeologists on the ground use test pits to sample an area in a quick manner so they can get a better understanding of the entire site. The same is the intention of SQuARE.

"What we'll learn is how objects circulate around the space station, and how long they stay in one spot. It's about the patterns and routines of everyday life in microgravity," said Alice Gorman, Walsh's counterpart as co-principal investigator of the project and one of the world s leading scholars in the field of space archaeology. "If the same artifact type appears frequently in all six squares, which cover areas used for working, eating and performing experiments, then that may indicate it's an artifact with high multi-functionality: the sort of thing you want to make sure you have lots of when you're in a space station orbiting the moon or on the surface of Mars."

The photographs may also expose crew habits and routines that can inform future spacecraft designs, Gorman told collectSPACE.

"There may be Velcro patches on the walls which are never used, and others that always have objects stuck to them. We can document that and make hypotheses about the activities and behaviors which cause this pattern. Then we can make recommendations for the placement of these 'gravity surrogates' in newer space habitats, to increase crew efficiency," she said.

SQuARE is just the first in a series of studies that the International Space Station Archaeological Project hopes to conduct aboard the orbital complex. The team applied to the National Science Foundation for the funding needed for seven different experiments that would ask astronauts to conduct a variety of activities, from swabbing surfaces to recording sound to making videos discussing their experiences.

As a first foray into space, SQuARE holds the potential of delivering new insight into astronauts' activities, from the perspective of a field new to the frontier.

"Since this is the first collection of archaeological data ever attempted in a space habitat, we're not exactly sure what we'll find. It is an experiment, after all," Walsh and Gorman wrote. "But we are sure that the results will illuminate aspects of life in space that no-one, not even NASA, has ever known before."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2022 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.