Millie Hughes-Fulford, NASA's first female payload specialist in space, dies at 75

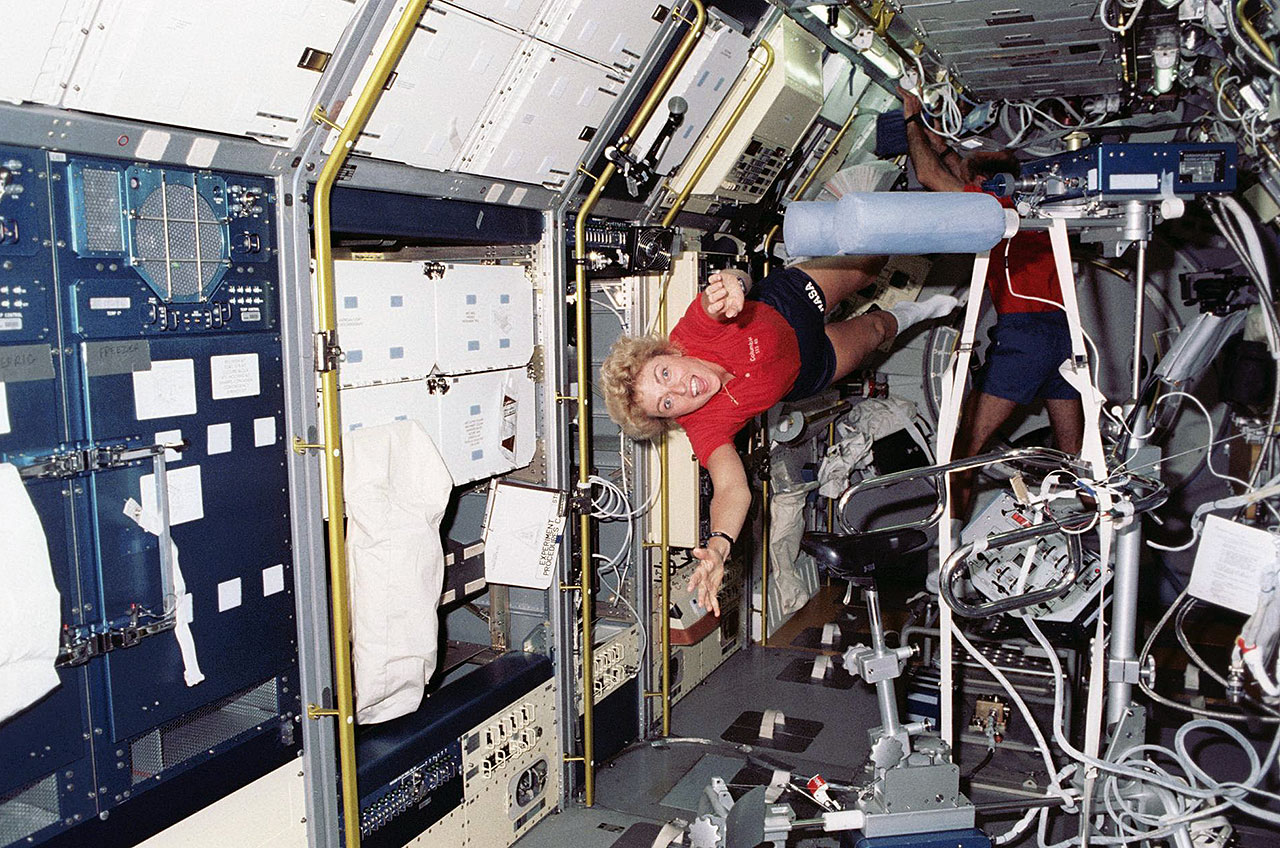

Hughes-Fulford launched on the STS-40 space shuttle mission in June 1991.

The first American woman to launch into space who was not a professional astronaut but a working scientist, Millie Hughes-Fulford, has died at the age of 75.

Hughes-Fulford's death was confirmed by the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation (ASF) on Thursday (Feb. 4).

"We are grateful for her research and advancements with her work in the life sciences. Please join us in expressing our sympathy to Millie's family and friends at this time," Caroline Schumacher, ASF president and chief executive officer, wrote in an email.

NASA's space shuttle program in pictures: A tribute

Originally selected by NASA in 1983 to train as a non-career astronaut for a science-dedicated space shuttle mission, Hughes-Fulford's first and only launch was delayed by the 1986 Challenger tragedy. Lifting off on the space shuttle Columbia on June 5, 1991, Hughes-Fulford became the first female payload specialist to enter orbit and a member of the first crew to include three women.

She was also the first person to fly into space to represent the U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs (VA), having been a molecular biologist at the VA medical center in San Francisco at the time.

"It was a life's dream, and not many of us get our life's dream," Hughes-Fulford said in a 2014 interview with the VA.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I was watching Buck Rogers in 1950 when I was 5 years old, and their pilot was a woman named Wilma Deering. I wanted to be Wilma Deering because she could wear pants. At that time a little girl could not go around in pants. I would sneak off in my pair of Levi's and I would hear, 'Get out of those Levi's, put your dress on!'" she said. "And so I wanted to be Wilma Deering because she could wear anything she wanted to, she flew a spaceship and was a professional woman."

"It was a dream and it turned into reality, which was awfully nice," she said.

As a member of the STS-40 crew, Hughes-Fulford was responsible for overseeing some of the experiments aboard Spacelab Life Sciences 1 (SLS-1), the fifth Spacelab mission and the first dedicated solely to biomedical research. As a cell biologist, one of her tasks was to help in the collection of her crewmates' blood.

"It wasn't like you just drew a tube of blood and put in the refrigerator. It was, you have to do a finger stick and get a hematocrit. You have to draw blood for this and spin it and separate the serum from the blood. You have to put this one in the refrigerator right away. It was like you collect six or seven things for each draw, and then you've got four people, so you've got lots of different moving parts," said Rhea Seddon, one of Hughes-Fulford's STS-40 crewmates, in a 2011 NASA oral history interview.

The STS-40 crew completed more than 18 experiments (including 10 involving humans, seven involving rodents and one with jellyfish) and returned to Earth with more medical data than any prior NASA spaceflight. "We're at 140% of what we expected to do," Hughes-Fulford said in a televised interview while in space.

But even after logging 9 days, 2 hours, 14 minutes and 2 seconds off the planet, Hughes-Fulford's mission was not over. Together with Seddon, mission specialist Jim Bagian and fellow payload specialist Drew Gaffney, Hughes-Fulford remained for a week at the landing site to continue providing data on how the human body readjusted to gravity.

Related: Weightlessness and its effects on astronauts

Millie Elizabeth Hughes-Fulford was born in Mineral Wells, Texas, on Dec. 21, 1945. Entering college at the age of 16, she earned her Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry and biology from Tarleton State University in 1968, and then studied plasma chemistry at Texas Woman's University as a National Science Foundation Graduate Fellow from 1968 to 1971.

Upon completing her doctorate at Texas Women's University in 1972, Hughes-Fulford joined the faculty of Southwestern Medical School at the University of Texas, Dallas as a postdoctoral fellow, where her research focused on the regulation of cholesterol metabolism. She also served as a major in the U.S. Army Reserve Medical Corps from 1981 through 1995.

At first assigned to backup payload specialist Robert Phillips on the SLS-1 (STS-40) mission, Hughes-Fulford joined the prime crew after Phillips was medically disqualified from flight.

Following her spaceflight, Hughes-Fulford returned to the VA medical center in San Francisco, where she became director of the laboratory that now bears her name. She was a contributor to more than 120 papers and abstracts on T-cell activation, bone and cancer growth regulation and continued to conduct research in space as the principal investigator for experiments that flew aboard STS-76 in March 1996, STS-81 in January 1997 and STS-84 in May 1997, examining the root causes of osteoporosis that occur in astronauts while in microgravity.

She also flew experiments aboard Soyuz and SpaceX Dragon spacecraft to the International Space Station, studying the decrease in T-cell activation — a medical problem that was first found in returning Apollo astronauts — and how isolated T-cells were activated in spaceflight. (T-cells are a type of white blood cell that is of importance to the body's immune system.)

"If you think of it, we all evolved in a gravity field. When we go into spaceflight and we have microgravity, we have eliminated one variable. In mathematics, if you get rid of a variable, you can solve the equation, and we're able to look at the immune system in a whole new way that has not been possible," Hughes-Fulford said in a video interview for the ISS National Laboratory in 2015.

A recipient of the NASA Space Flight Medal in 1991, Hughes-Fulford's research on board the space station was awarded by NASA as a Top Discovery on ISS.

Hughes-Fulford was married to George Fulford, who preceded her in death. She is survived by their daughter, Tori Herzog.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2021 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.