Philip Chapman, first Australian-born NASA astronaut, dies at 86

An Apollo-era NASA astronaut who was the first person born in Australia to train for a spaceflight, Philip Chapman has died at the age 86, having never made it into orbit.

Chapman died on Monday (April 5) in Scottsdale, Arizona, almost 50 years after he resigned from NASA due to what he saw as a lack of opportunities for scientists in the astronaut corps.

"We are saddened to learn of the passing of Australian-born astronaut, Dr. Philip Chapman," wrote the staff at the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, part of NASA's Deep Space Network in Australia, on Twitter Wednesday.

Selected in 1967 after he became a U.S. citizen, Chapman was a member of NASA's sixth class of astronaut trainees. Chosen with 10 other scientists, the group nicknamed themselves "The Excess Eleven" (the "XS-11") in light of their being told from the start that their chances of flying into space were slim.

"What motivated me to join the program is that I was deeply interested in space technology. I was in this country so I could work on space technology. NASA called for applications to become scientist-astronauts and that is as close as you can get to space technology," said Chapman in a 1969 interview with ABC News' (Australia) Weekend Magazine.

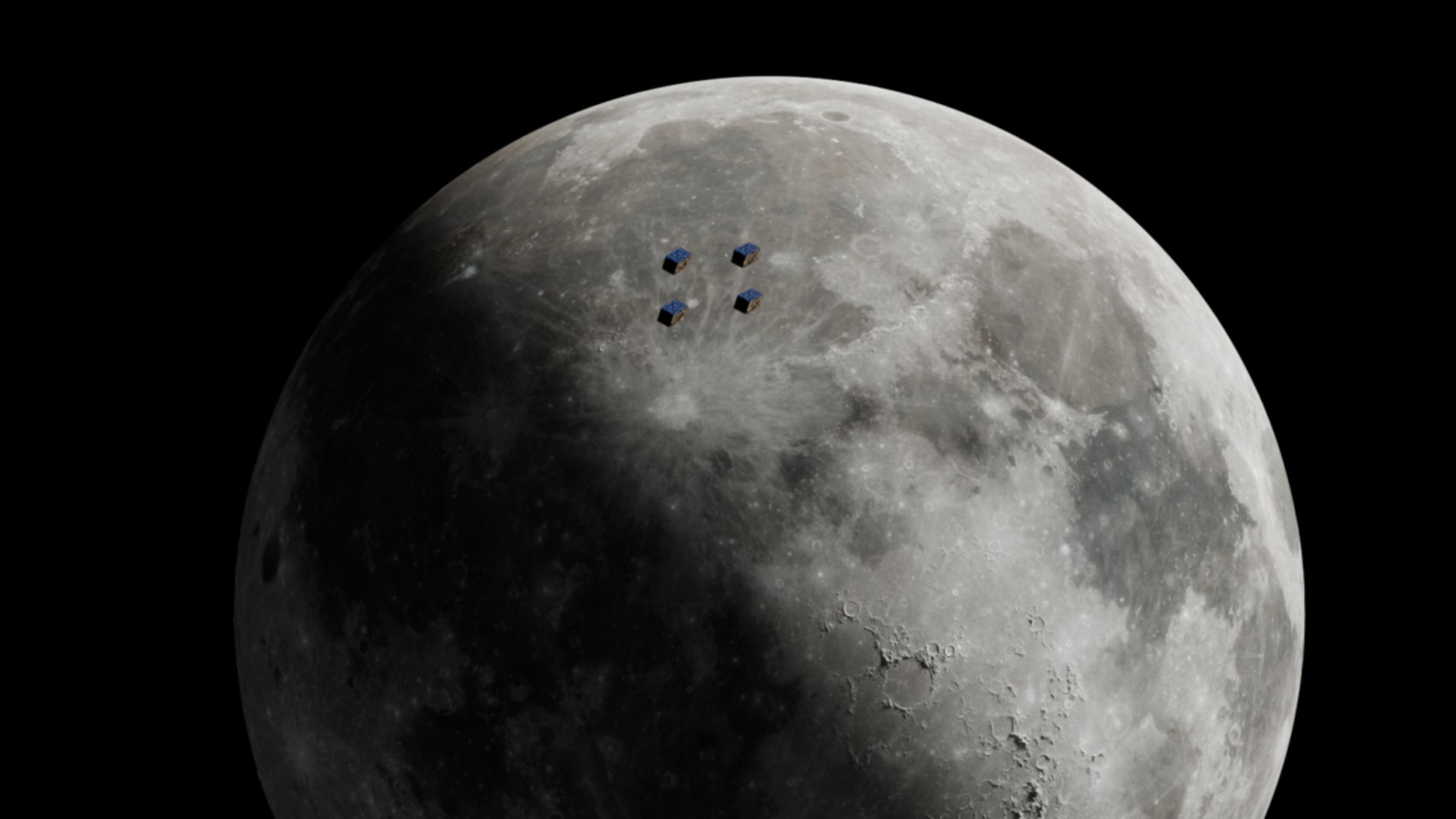

After undergoing basic astronaut training, including spending more than a year learning how to fly NASA's T-38 supersonic training jets at Randolph Air Force Base in Texas, Chapman was assigned to support roles for the then underway Apollo moon landings. Most notably, he served as mission scientist for Apollo 14, which would land Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell on the lunar surface while Stu Roosa remained in orbit in 1971.

Related: What It's Like to Become a NASA Astronaut

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I'm not in charge of them, I am coordinating them," Chapman said of the Apollo 14 science experiments and his role as mission scientist, in a news interview at the time. "I am acting as the liaison between the experimenters and the crew."

That distinction was a point of contention for Chapman, who ran into objections when trying to suggest additional experiments for Roosa to perform while circling the moon. There was an opinion within the program that the mission would be more readily declared a success in the press if the number of objectives were kept to a minimum.

"I was dumbfounded by the idea that the way to increase interest in spaceflight was to minimize the useful results, and insubordinate Australian that I am, I told Deke [Slayton, the director of flight crew operations] what I thought of his new policy," Chapman said in an interview for the 2019 book "Shattered Dreams: The Lost and Canceled Space Missions" by Colin Burgess (University of Nebraska Press).

Still, Chapman suggested one of the more memorable science demonstrations to be carried out on the moon.

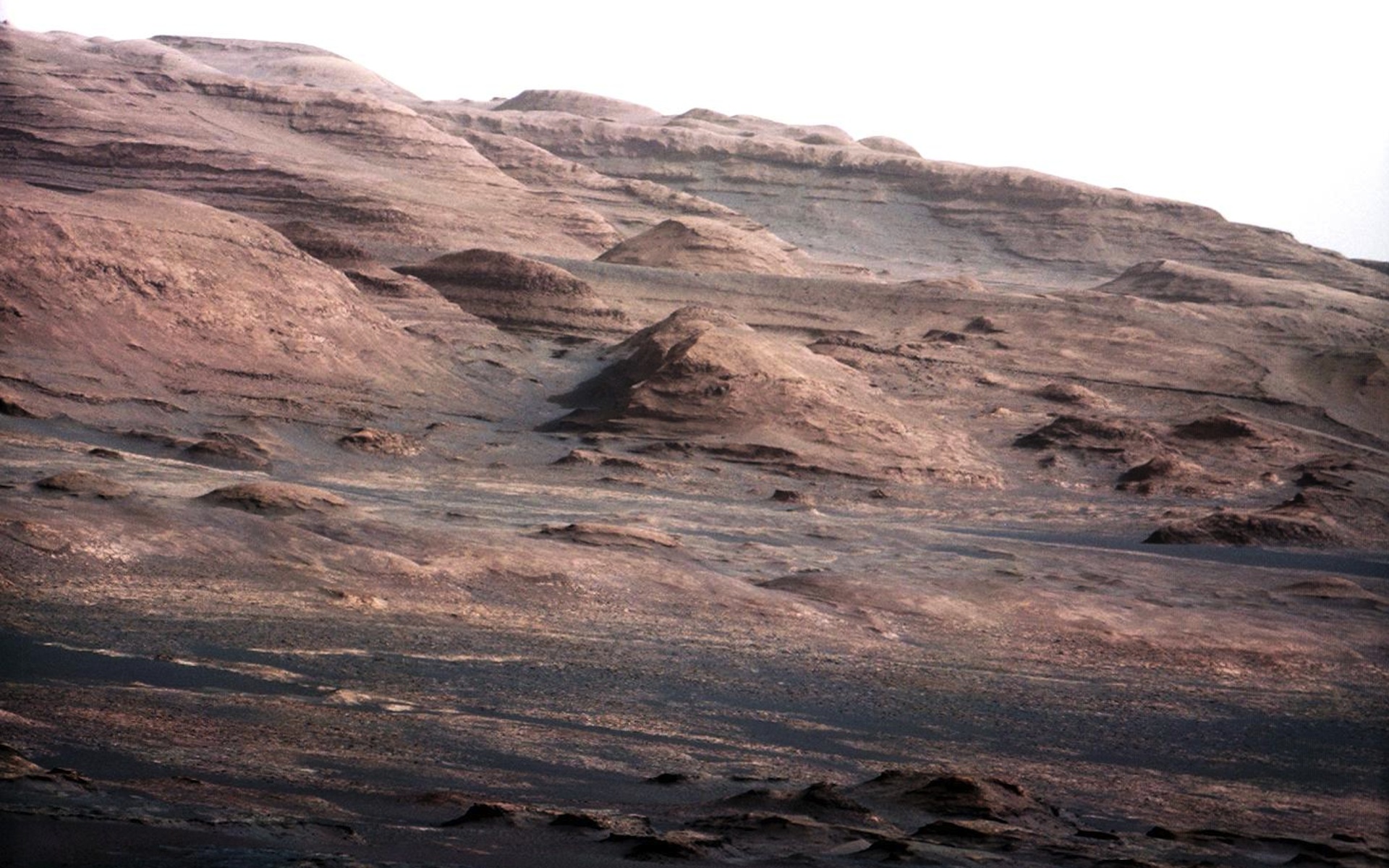

"I recall commenting to [Apollo 15 support crew member and capcom] Joe Allen that the moon would be a great place to repeat Galileo's famous demonstration at the Leaning Tower of Pisa, because the objects would fall slowly, and in vacuum," Chapman said of what would become Apollo 15 commander David Scott's famous "hammer and feather" drop in an interview with Emily Carney for her "This Space Available" column published by the National Space Society. "If I had thought about it seriously, I would have suggested it to Al Shepard on Apollo 14 — but perhaps he would have preferred his demonstration of golf on the moon."

With budget cuts drawing the Apollo program to its end and his chances of flying on board the Skylab orbital workshop all but nil, Chapman resigned from NASA in July 1972.

"It appears that we have to make a choice between losing our competency as pilots or losing our competency as scientists, said Chapman, as reported by The Associated Press at the time.

Born in Melbourne, Australia, on March 5, 1935, Philip Kenyon Chapman grew up and attended school in Sydney, earning his bachelor's in physics and mathematics from the University of Sydney in 1956.

"I'm delighted to have been an Australian — I'm American now," said Chapman in the 1969 ABC News interview. "I don't feel it is particularly significant in terms of what I am doing in the program. It is a matter of sheer chance but I am happy it turned out that way."

After serving with the Royal Australian Air Force for two years and spending 15 months at Mawson Station in Antarctica as an auroral/radio physicist, he worked for a year as an electro-optics staff engineer on flight simulators in Quebec, Canada, before becoming a staff physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he earned his masters in aeronautics and astronautics in 1964 and doctorate in instrumentation in 1967.

After his five years with NASA, Chapman briefly worked on laser propulsion and the concept of solar power satellites at the Avco Everett Research Laboratory in Massachusetts before turning his attention to commercial spaceflight. He was elected president of the L5 Society (today, the National Space Society) and served on the Citizens' Advisory Council on National Space Policy and then became chief scientist for two companies, Rotary Rocket and t/space, which were independently developing commercial reusable spacecraft to advance the space economy and service the International Space Station.

In 2009, Chapman returned to the study of space-based power, founding the Solar High Study Group, to further the development of solar power satellites.

Chapman is survived by his wife of 37 years, Maria Tseng. He is preceded in death by his first wife, Pamela Gatenby, with whom he had two children, Peter and Kristen.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2021 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.