Astronomers baffled by 'mysterious disruptor' with a mass of 1 million suns and a black hole for a heart

"This is a structure we've never seen before, so it could be a new class of dark object."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A completely dark and mysterious body with the mass of 1 million suns and a possible black hole heart continues to baffle and intrigue astronomers despite further investigation.

This "mysterious disruptor" is located around 11 billion light-years away and was discovered in 2025 thanks to its gravitational influence. It is now the most distant body ever detected due to its gravitational effects alone.

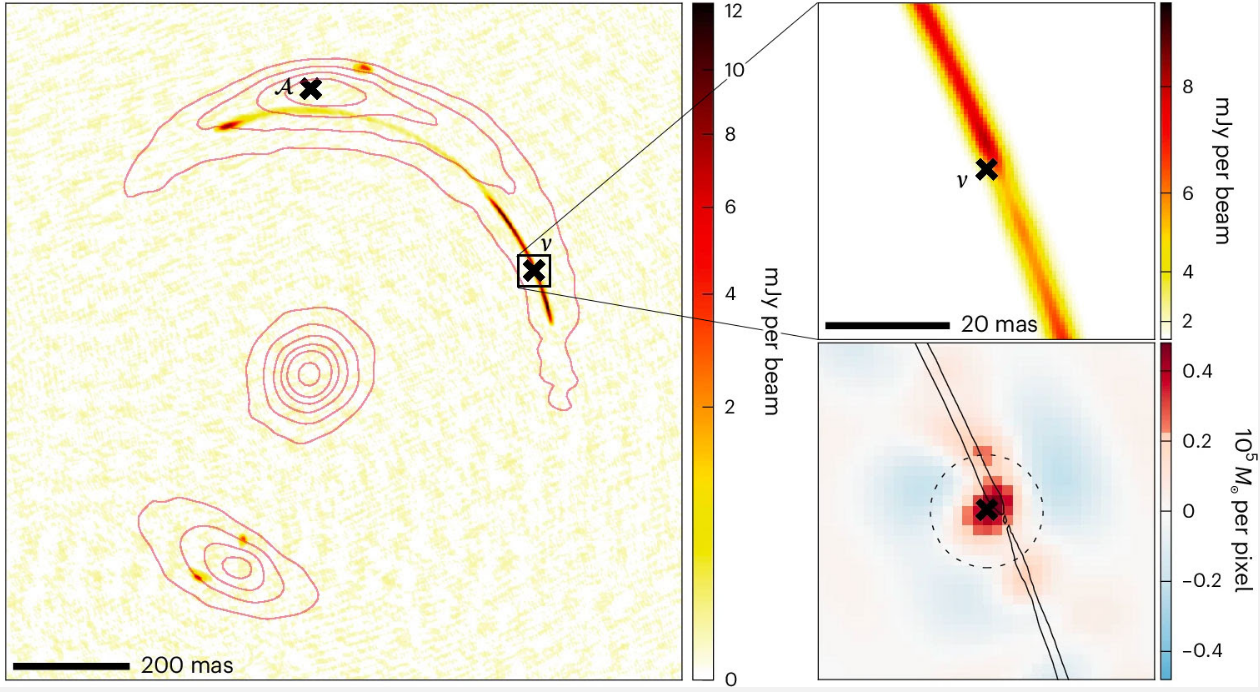

But astronomers aren't completely in the dark about the mysterious disruptor, however. In fact, they are sure they know what lies at the heart of this strange cosmic body. "The inner central part is consistent with a black hole or dense stellar core, which surprisingly makes up about a quarter of the object's total mass," Vegetti explained. "As we move away from the center, however, the object's density flattens into a large disk-like component. This is a structure we've never seen before, so it could be a new class of dark object."

This strange structure was found in the gravitational lens system JVAS B1938+666. Gravitational lensing is a phenomenon first predicted by Einstein in the 1915 theory of gravity known as general relativity. It occurs when light from a background source passes the curvature of space caused by a massive foreground object, known as a gravitational lens, causing its usually straight path to become curved. The way light is influenced doesn't just allow objects to be seen at great distances via light amplification, but also tells scientists a great deal about the way mass is distributed within the lensing system itself.

The gravitational lens JVAS B1938+666 consists of massive bodies ranging from 6.5 billion to 11 billion light-years away, including this "mysterious disruptor," the most distant element of Jvas B1938+666. A team of astronomers attempted to reconstruct the distribution of mass in the object, revealing its so-called "density profile."

That's a highly complex procedure considering JVAS B1938+666 consists of many different bodies, the main component of which is a massive elliptical galaxy. Unlike those other bodies, however, the mysterious disruptor is completely invisible.

"Trying to separate all the different mass components of such a distant, low-mass object using gravitational lensing was extremely challenging and incredibly exciting," team leader Simona Vegetti of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Germany, said in a statement. "We're working with high-quality data and complex models, and just when I thought we had it all figured out, its properties threw up another surprise. "It's precisely this combination of difficulty and mystery that makes this object so fascinating."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

What do we know about the mysterious disruptor so far?

To investigate the mysterious disruptor, Vegetti and colleagues first set about analyzing the small disturbances, or perturbations, that it makes to the overall arc of the gravitational lens JVAS B1938+666. They then compared data collected by an array of telescopes, including the Green Bank Telescope, to various models of dark matter. This revealed that none of these models could explain the mysterious disruptor.

"It has a very strange profile, because it's particularly dense at the center, but it extends enormously," team member Davide Massari of the National Institute for Astrophysics said. "So it's not uniformly distributed: it's as if there were an extremely compact object at the center, but then the profile continues to extend to distances much greater than those typically observed in galaxies or star systems of comparable mass."

Though investigations of the mysterious disruptor have thus far involved radio telescopes, future studies and a potential solution to this conundrum could come courtesy of telescopes operating in other wavelengths of light, including the powerful infrared vision of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)."If we were finally able to observe some form of light emission in the visible or infrared range, we could conclude, for example, that it is a somewhat anomalous ultracompact dwarf galaxy, with an unusually extended stellar halo," team member Cristiana Spingola of the National Institute for Astrophysics. "But if even with JWST we still fail to see starlight or other visible matter, then it would mean that we are dealing with an object whose properties are difficult to explain with current dark matter models."

The team's research was published on Monday (Jan.5) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.