Astronomers discover cosmic hamburger has the potential to grow giant planets

"The combination of extreme disk size, strong asymmetries, winds, and potential planet formation makes it the perfect laboratory for understanding how giant planets can form."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

If you've ever discovered something completely unexpected in your hamburger, it was likely that neither delight nor intrigue were your first reaction. However, that isn't the case for a team of astronomers who have recently discovered something they didn't predict in a "cosmic hamburger," one of the biggest planet-forming disks of gas and dust, or protoplanetary disks, humanity has ever seen.

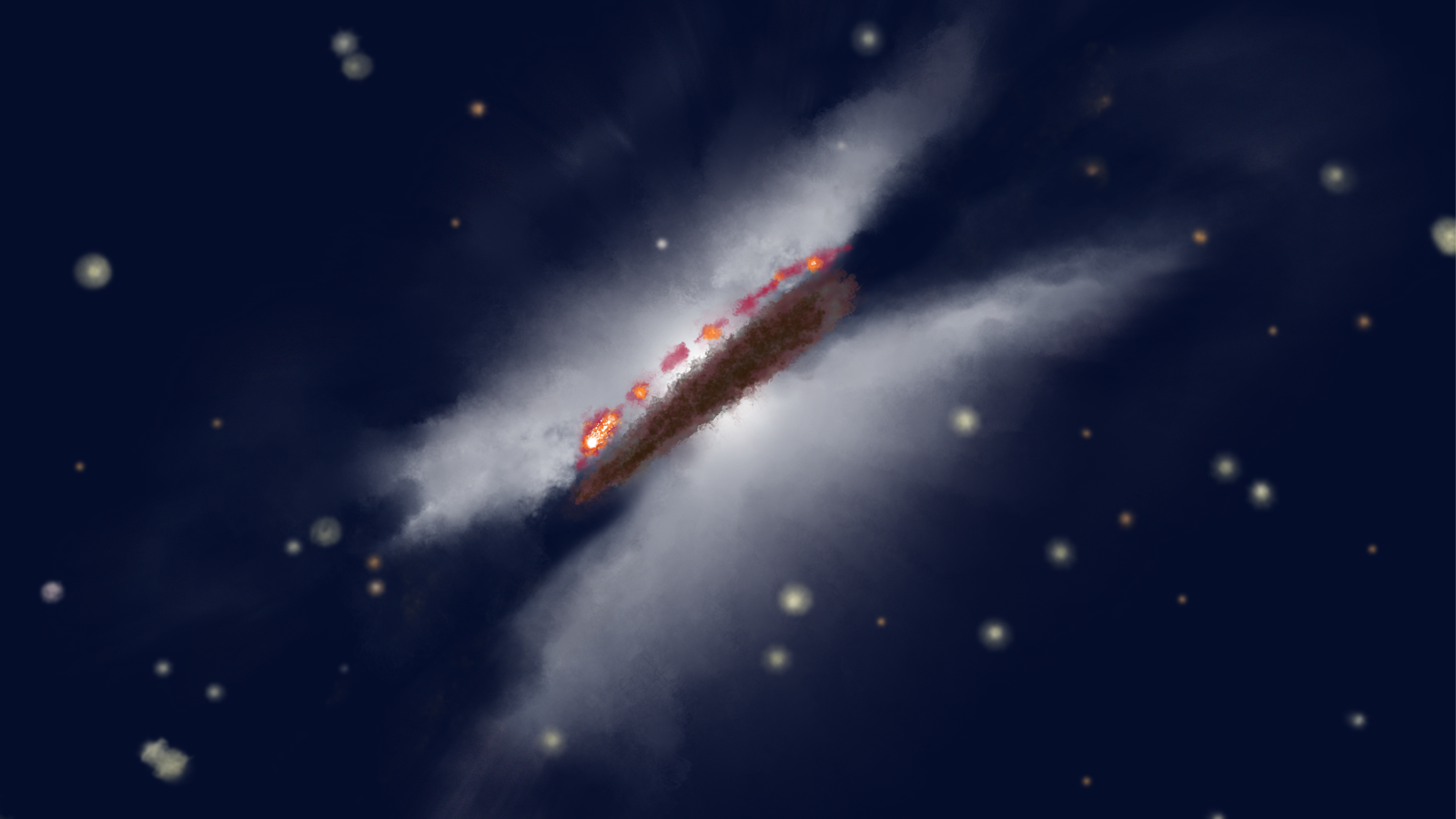

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a powerful array of 66 radio antennas located in northern Chile, the team discovered the first signs of planet formation in the dense gas layers of a system known as Gomez's Hamburger (GoHam). GoHam's tasty appearance is due to the fact that from Earth it is seen edge-on with stacked layers of gas "buns" rotating around a young star "burger." This orientation allows the structure of Go Ham to be viewed in a way that isn't possible for other protoplanetary disks swirling around similar young stars. As such, the study of GoHam and the discovery of tantalizing hints of planet formation could give astronomers a better understanding of how giant planets form at great distances from their parent stars.

"GoHam gives us a rare and clear view of the vertical and radial structure of a very large, nearly edge‑on disk," team leader Charles Law of the University of Virginia said in a statement. "This makes it a benchmark system for testing detailed models of how disks evolve and form planets. The combination of extreme disk size, strong asymmetries, winds, and potential planet formation makes it the perfect laboratory for understanding how giant planets can form far from their star, and how their presence reshapes the surrounding gas and dust."

GoHam is nothing like the image on the menu

ALMA's intricate observations of GoHam allowed Law and colleagues to map the locations of dust grains and gas molecules in the system, finding they had arranged themselves into distinct layers. These gases include two forms of carbon monoxide and several sulfur-based molecules.

The lightest of these gases dwells above the midplane of GoHam, while heavier gases sit closer to this midpoint, leaving the heaviest molecules closest to the midplanes, exactly the sort of ordering or "stratification" that astronomers would expect to see in a system like this.

While the system's dust and large solids are concentrated at the middle of GoHam, its gas is puffed out to a width equivalent to 2,000 times the distance between the sun and the Earth, and it reaches up to a height of several hundred times this distance. That makes GoHam one of the largest protoplanetary disks ever discovered.

This system is also remarkable for the amount of dust it contains, which is estimated to be many times greater than the dust content of similar protoplanetary disks around young stars. Thus, the potential for GoHam to grow giant planets is huge, meaning this could in the future host a multiplanet system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, just like your fast food burger never quite looks like the image on the menu, GoHam isn't perfectly formed. In fact, this cosmic burger is lopsided. One side of the disk has an extended and brighter dust emission, which could be the result of a disturbance, possibly a vortex, that is trapping solids. These will become the building blocks of planets in the system.

The northern side of the disk shows traces of a "photoevaporative wind," a phenomenon that occurs when starlight blows gas away from the disk and into space. The team also detected an arc of sulfur monoxide beyond the dust of the disk, but only on one of its sides. This arc aligns with a dense clump of material labelled "GoHam b," which astronomers believe is matter collapsing under its own gravity.

This is likely to be the earliest stage of planet formation in the outer disk of GoHam, which could be a giant planet in a wide orbit far from its parent star.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.