To find features like groundwater under Earth's surface — or under the surface of another world — scientists can sense the subtle marks those features leave in the planet's gravitational field.

But those measurements aren't easy to get; you need very sensitive instruments, and even the slightest vibrations can throw off the measurements. Now, a group of physicists has demonstrated an hourglass-like gravity-measuring device that they say helps to overcome this challenge.

Gravity-measuring devices, called gravimeters, themselves aren't new. They're used for everything from probing physical constants to mapping rugged landscapes. Modern, cutting-edge gravimeters use atoms. If you pulse two atoms with lasers and send them out to different points, a gravitational field will affect the two in slightly different ways. You can measure that gravitational field by overlapping those two atoms and puzzling out the differences in their quantum properties.

Related: 10 mind-boggling things you should know about quantum physics

But when physicists try to boost the resolution in attempts to see objects the size of a few meters, such as pipes and passages underground, conventional gravity sensors hit a wall. Ground variations, temperature shifts and even slight magnetic fields can throw them off.

So the new sensor takes a different approach. The researchers call it an hourglass; each "bulb" contains a cloud of rubidium atoms trapped in a magnetic cage, pulsed through with a laser. The dual clouds mean that that device effectively has two separate gravimeters. As a result, the researchers can not only measure a gravitational field but also measure it at two different heights.

It's not the most sensitive quantum gravity sensor in the world, but it is one of the first to leave the lab. In a real-world test, this hourglass-like gravimeter detected a utility tunnel buried under a road in Birmingham, England.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As far as we know, our instrument has been the first to detect a real underground target of relevance to civil engineering outside of the laboratory environment," study co-author Kai Bongs, a physicist at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, told Space.com. "This is really a breakthrough in making quantum technology practical."

The new gravimeter could become a wonderful tool for mapping built-up features underground.

And these gravimeters aren't limited to use on Earth. In fact, the European Space Agency (ESA) is already interested in taking them to the launchpad. ESA's next generation of Earth observation satellites might carry sensors like these, measuring things like underground water, the circulation of the world's oceans and how these things are being affected by climate change.

"This might be extended to the exploration of other planets in the solar system, understanding more about their inner structure," Bongs told Space.com.

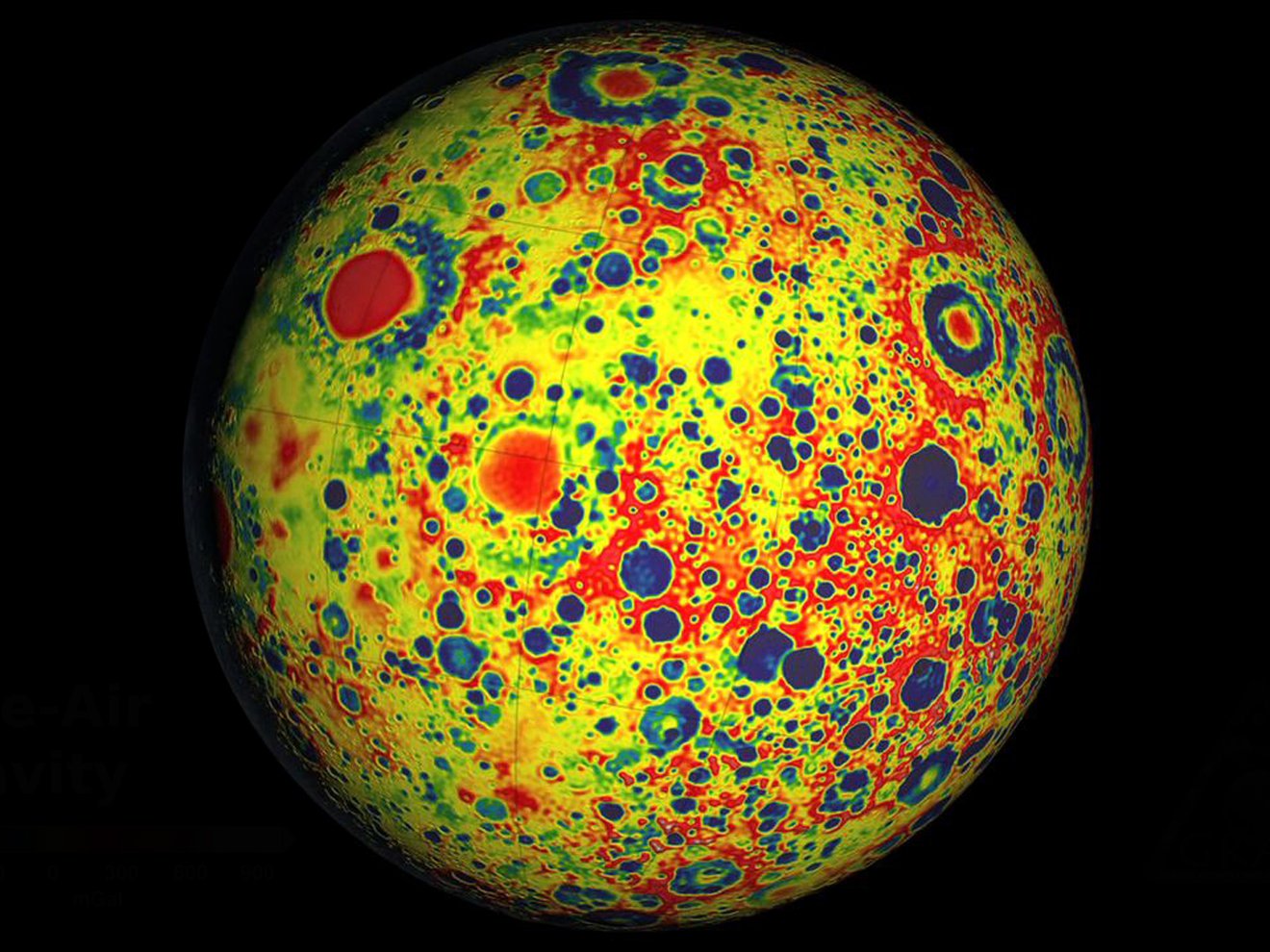

Sending gravimeters to study other worlds isn't new. In 2012, NASA's GRAIL mission sent a pair of spacecraft to map the moon's gravitational field and peel away its surface. That mission probed the layers of the moon's interior with unprecedented accuracy, studied the material under impact basins and found what might be the signatures of underground caverns.

Now, if ESA's interest is any indication, these next-generation gravimeters could be used to find underground water on the moon — or on other worlds, like Mars.

The researchers published their work Feb. 23 in the journal Nature.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.