'Sub-Earth' exoplanet discovered around the closest solo star to us

"Barnard b is one of the lowest-mass exoplanets known and one of the few known with a mass less than that of Earth."

Astronomers have discovered a planet orbiting the closest solo star to the solar system, known as Barnard's star. The newly discovered exoplanet has around half the mass of Venus, which classifies it as a "sub-Earth."

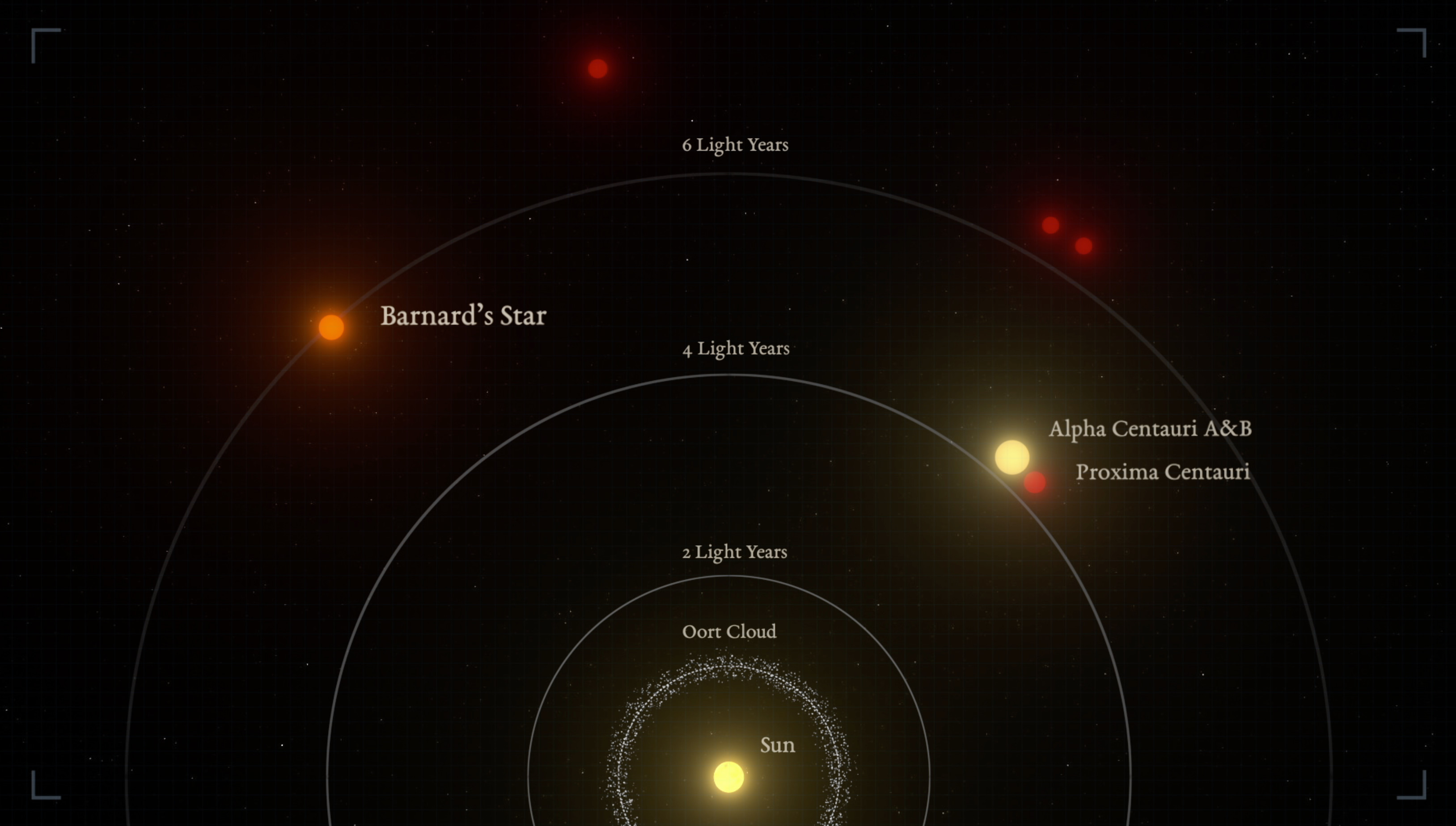

The exoplanet, designated Barnard b, takes just over three Earth days to orbit its red dwarf parent star, which is located around six light-years away. That's because Barnard b is just around 1.8 million miles from Barnard's star. Although this may sound like an immense distance, it is only 5% of the distance between the sun and its closest planet, Mercury.

"Barnard b is one of the lowest-mass exoplanets known and one of the few known with a mass less than that of Earth. But the planet is too close to the host star, closer than the habitable zone," team leader Jonay González Hernández, from the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Spain, said in a statement. "Even if the star is about 2,500 degrees cooler than our sun, it is too hot to maintain liquid water on the surface."

González Hernández and colleagues discovered Barnard b using the Very Large Telescope (VLT), an array of four telescopes located on the mountain Cerro Paranal in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope finds 'puffball' exoplanet is uniquely lopsided

The exoplanet revealed itself via the tiny "wobble" it causes in the motion of its red dwarf star as it orbits that star, gravitationally tugging on it. This detection was possible thanks to the VLT instrument called "the Echelle Spectrograph for Rocky Exoplanet and Stable Spectroscopic Observations," or ESPRESSO. The initial detection was then confirmed using data from the exoplanet-hunting High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS).

Hello neighbor(s)!

Barnard's star isn't the closest star to the solar system; that honor goes to the Alpha Centauri stars, Proxima Centauri, Centauri A and Centauri B. The distinction between these stars and Barnard's star is that they are part of a multi-star system, while Barnard's star flies solo, just like the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The proximity of Barnard's star to our planet has made it a prime target in the search for Earth-like rocky planets.

Additionally, low-mass terrestrial exoplanets are easier to detect around red dwarfs like Barnard's star, which also happen to be the most common stars in the Milky Way.

Barnard's star has a surface temperature of just around 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,800 degrees Celsius) compared to the 10,000 Fahrenheit (5,600 Celsius) surface temperature of the sun. The red dwarf star is 80% smaller than the sun.

However, there is another important difference between Barnard's star and the sun; this red dwarf is also thought to be less rich in "metals," the name that astronomers give to elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. Metal-poor stars are thought to be at a disadvantage in forming terrestrial planets in orbits around them.

That didn't deter González Hernández and the team from scouring the region around Barnard B for signals from possible exoplanets. The team has been particularly interested in rocky worlds in the habitable zone around this close star.

This region, also known as the "Goldilocks zone," is special because it is the area around a star that is neither too hot nor too cold to allow liquid water to exist on an orbiting planet without boiling away or freezing.

"Even if it took a long time, we were always confident that we could find something," González Hernández said.

The same team also found tantalizing hints of another three potential exoplanets around Barnard's star, which they aim to confirm with ESPRESSO.

"We now need to continue observing this star to confirm the other candidate signals," team member Alejandro Suárez Mascareño, a researcher also at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, said in the statement. "The discovery of this planet, along with other previous discoveries such as Proxima b and d, shows that our cosmic backyard is full of low-mass planets."

The team's research was published on Tuesday (Oct. 1) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Helio Reply

Curious that it took this long to find it given it's a close neighbor.Admin said:Astronomers have discovered a low-mass "sub-Earth" planet orbiting the closest solo star to the solar system, Barnard's star, that has a year lasting just three Earth days.

Sub-Earth' exoplanet discovered around the closest solo star to us : Read more

But it has a solar equivalent distance of 0.41, so it gets a little more than the scorching radiation that Mercury does. But it is, no doubt, tidally locked, hence the cool side might have some interesting places to visit. -

Helio Reply

Yes, but when it comes to a fork in the road, they seem to take them.billslugg said:"Nobody goes there any more. It's too crowded" - Y.Berra -

billslugg When you live on a tidally locked planet with a 4 day year, the inhabitable zone would be a narrow strip around the edge. You might get just enough light reflected down into your lair to stay warm but not enough to kill you. Librations would be highlighted on the evening news when previously shaded areas were expected to receive sunlight. "Burn warning in sector four after 3PM!! Bring in your mutant plants!"Reply -

Unclear Engineer Joking aside, would a planet that close to a red dwarf even be expected to retain an atmosphere for long enough to evolve life?Reply

I did not see anything that indicated any interest in trying to find life on that planet.

My reading of the importance of this discovery was more along the lines that a rocky planet still formed around a small "metals-poor" star, and that indicated something important for scientists who are trying to understand how planets evolve from clouds of gas and dust as they form stars. -

Helio Besides at the terminator, there does seem to be some additional hope for Mercury-like planets (hot and tidally locked). The tidal-lock allows the dark side to be frozen, but it doesn't prevent subsurface water, including liquid water, which is maintained by interior heating.Reply

Larger ones in tight orbits have been found with atmospheres. I think one was found to have atmospheric winds over 20k mph. Atmospheres may have the ability to reduce the temperature differences enough to allow surface water.

What is needed for any real hope for habitability seems to be "shelter, energy, nutrients, and sources of carbon" (P148). A great deal of liquid water is being found on planets (including Mercury) and moons (e.g. our Moon). The moons may be more favorable since they benefit the most from tidal friction, thus can stay warm enough to keep water liquid for "billions of years".

The more ubiquitous these requirements are found, the more optimistic scientists become. Certainly reasonable, but until some hard evidence is found for current or prior living organisms elsewhere, and not from Earth contaminates, then this is still a hypothesis in waiting, IMO.