BepiColombo spacecraft records the sound of solar wind at Venus

The probe has made detailed measurements of Venus's cloudy atmosphere. Could it find life?

The Mercury-bound BepiColombo spacecraft listened to the sound of the solar wind at Venus as it flew just 340 miles (550 kilometers) above the planet's surface during a maneuver designed to adjust its path.

BepiColombo, a joint mission by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), recorded the audio with its magnetometer instrument, providing a rare glimpse into the interaction between the stream of charged particles flowing from the sun, known as solar wind, and the thick carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere of Earth's closest planetary neighbor.

The audio is not the actual sound that could be heard in space but a so-called sonification, a translation of data into sounds, ESA said in a statement.

Related: Watch the BepiColombo probe zoom by Venus on its way to Mercury in this new video

Studying Venus from multiple points

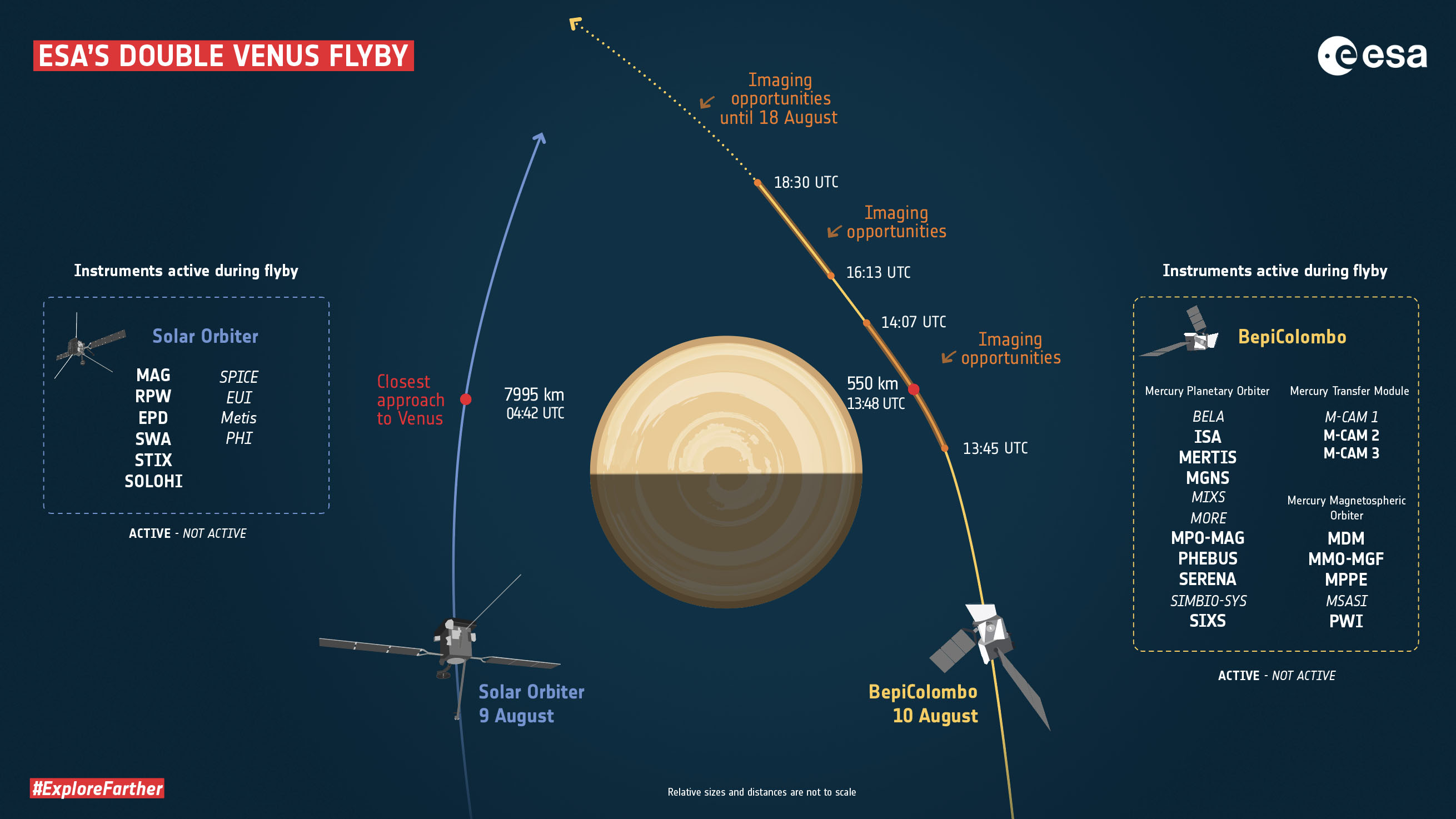

BepiColombo passed by Venus on Aug. 10, just one day after another inner-solar-system explorer, Solar Orbiter, made its own close approach. This coincidence enabled scientists for the first time to make measurements of the environment around Venus from multiple points.

Solar Orbiter, a joint mission by ESA and NASA, has a similar magnetometer in its instrument suite as BepiColombo. It has made its own measurements of the interactions between the solar wind and the planet as it zipped by at a distance of nearly 5,000 miles (8,000 km) on Aug. 9.

Flybys are a common maneuver used by spacecraft operators to adjust the trajectory of a spacecraft. By flying close to a planet or another celestial body with a strong gravitational pull, the spacecraft loses or gains energy, which helps "slingshot" it toward its destination in the most fuel-efficient way.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers are still analysing the data gathered by both spacecraft and hope that the Japanese mission Akatsuki, the only orbiter currently studying Venus, could contribute as well.

"This was the first time we could obtain such multi-dimensional measurements of the environment around Venus," Johannes Benkhoff, ESA BepiColombo project scientist, told Space.com. "That could enable us to see, for example, how the solar wind interacts with the planet and its atmosphere and how fast the processes are."

A detailed look at the composition of the atmosphere

BepiColombo could provide especially valuable data as the spacecraft swung closer to the surface of Venus during this flyby than Akatsuki gets at the closest point in its orbit around Venus.

According to Benkhoff, BepiColombo's Mercury Radiometer and Thermal infrared Imaging Spectrometer (MERTIS) instrument could therefore make unprecedented measurements of the middle layers of Venus's thick and cloudy atmosphere, known for its out-of-control greenhouse effect.

"We can look for carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide and other aerosols, which has not been done with this type of instrument before," Benkhoff said. "There hasn't been a European mission to Venus since Venus Express [which lost contact with Earth in 2014]. We hope to make some measurements with BepiColombo that could be compared to the Venus Express measurements to see how things have changed."

For example, Benkhoff added, changes in concentrations of sulfur dioxide could indicate changes in the volcanic activity on the planet's surface.

ESA said in the statement that the MERTIS instrument captured high-resolution spectra of the atmosphere of Venus that are similar to those obtained by the early 1980s Soviet Venera 15 mission. No other spacecraft has made such detailed measurements since, ESA said.

Finding life on Venus?

There has been a revival in the interest in Venus following last year's surprising indications that the boiling planet might harbor life.

In September 2020 a team of scientists from the U.K. announced that they had detected phosphines, organic compounds that are usually produced by bacteria, in the planet's sulfur-rich clouds. The conclusions were based on measurements obtained by Earth-based telescopes. This year, however, a study co-authored by astrobiologist Chris McKay, of the NASA Ames Research Center in California, concluded that the amount of water in the atmosphere of Venus is so low that it is impossible for any life to exist there.

Benkhoff said that BepiColombo is unlikely to solve the ongoing dispute, even though it will look for phosphines in the atmosphere.

"Our MERTIS instrument is in principle able to detect phosphines," Benkhoff said. "But we don't think that it is sensitive enough to detect the low amounts that are expected at Venus."

Getting ready for Mercury

The Aug. 9 flyby was the third of the overall nine required for BepiColombo to approach Mercury in the right way so that it can insert its two orbiters, the European Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the Japanese Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, into their correct orbits.

The innermost planet of the solar system is notoriously difficult to reach as the spacecraft has to continuously brake against the gravitational pull of the sun. For BepiColombo, this braking is achieved with the help of the gravity-assist flybys.

BepiColombo performed its first flyby at Earth in April 2020. Six months later, it made its first visit to Venus, passing at a much greater distance of 6,650 miles (10,700 km). On Oct. 1, the spacecraft will take its first look at Mercury from a distance of merely 125 miles (200 km). There will be five additional Mercury flybys to prepare BepiColombo for entering the planet's orbit in 2025.

The close Venus flyby, Benkhoff said, provided the first opportunity to test the spacecraft's instruments at a distance at which they will operate at Mercury.

"Our instruments were designed for orbiting Mercury at 400 to 1,500 kilometers," or 250 to 930 miles, Benkhoff said. "This Venus flyby provided us with the perfect opportunity to prepare not only for the mission but also for the upcoming first Mercury flyby."

BepiColombo has captured a sequence of photographs during the Venus flyby, which were released by ESA as a short video. The images were obtained by three low resolution 'selfie cameras' mounted on BepiColombo's propulsion module. The high albedo, or reflectiveness. of Venus, however, made it impossible for the cameras to capture any details of the planet's clouds.

The much darker Mercury, which lacks an atmosphere, will present a better photo opportunity, Benkhoff suggested.

"Venus was unfortunately quite overexposed in the images," Benkhoff said. "But we hope that at Mercury, even the selfie cameras might be able to identify some structures on the surface of the planet."

BepiColombo is fitted with a high-resolution stereoscopic camera, but that cannot be used during the cruise phase because of the spacecraft’s configuration in transit. The two orbiters and the propulsion module are stacked on top of each other, which blocks some of the instruments.

The October Mercury flyby will mark the first occasion any spacecraft will have visited the smallest and innermost planet of the solar system since the demise of the NASA mission Messenger in 2015.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.