Chance encounters: Mercury probe and sun spacecraft provide new info about Venus

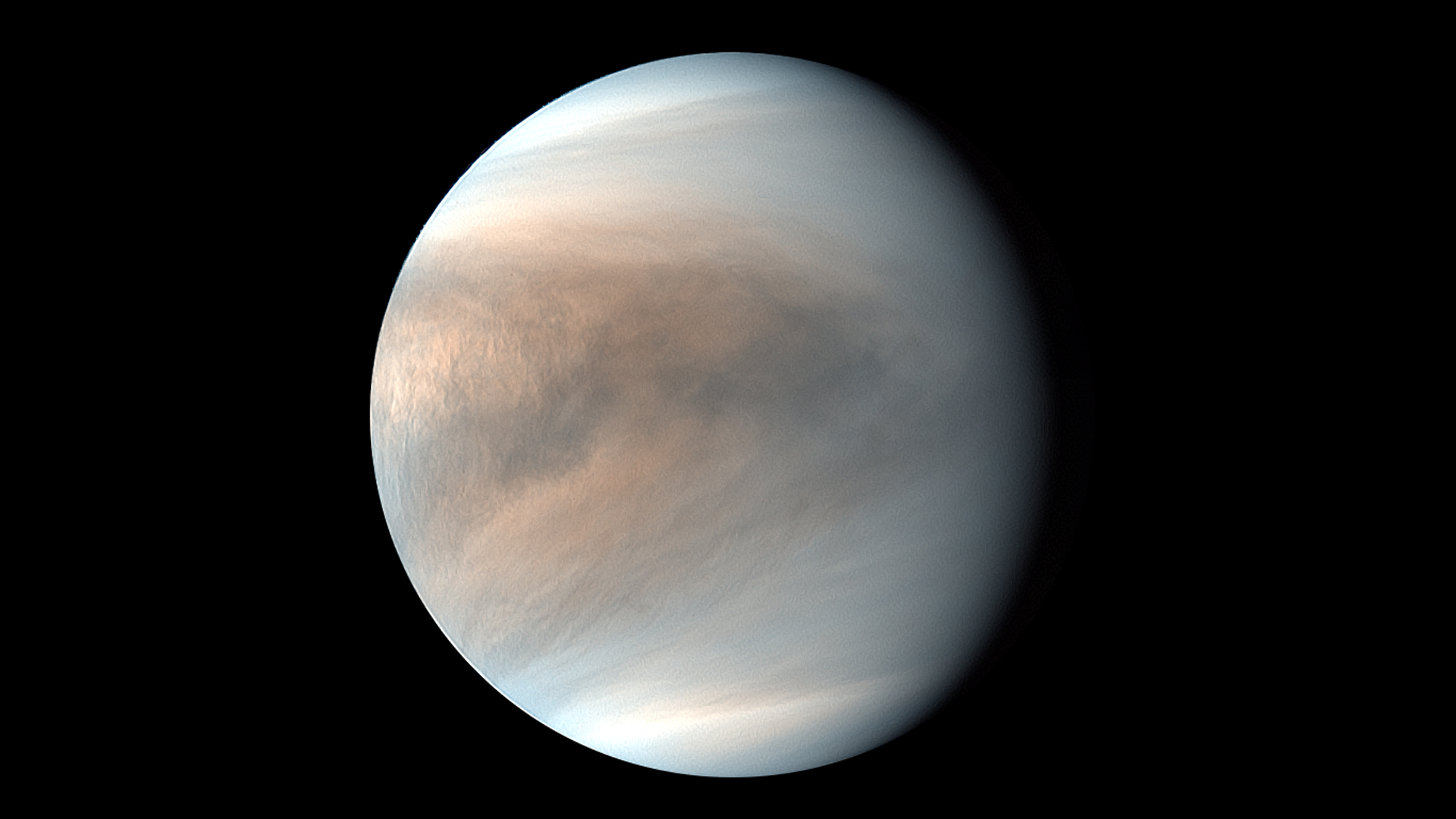

BepiColombo and Solar Orbiter are helping us better understand Earth's sister planet.

Space exploration missions always have a planned destination, but sometimes they swing by other planets on the way.

Two probes — BepiColombo, headed to Mercury, and Solar Orbiter, en route to the sun — recently passed by Venus at nearly the same time, visiting Earth's sister planet within a day of each other in August 2021. Their combined observations, recently published in the journal Nature Communications, give astronomers a rare glimpse into the workings of Venus' magnetic field.

"BepiColombo had a perfect view of the different regions within the magnetosheath and magnetosphere," said University of Tokyo astronomer Moa Persson, lead author on the new study, in a press release.

Related: Photos of Venus, the mysterious planet next door

Earth's magnetic field is a key reason why life has been so successful here. Magnetic fields help deflect high-energy particles streaming from the sun, known as the solar wind, protecting the fragile atmosphere of the planet. Venus isn't quite so lucky — it doesn't have a magnetic field created deep in its core like Earth does.

However, Venus does have something known as an "induced" magnetic field, in which the solar wind interacts with charged particles in Venus' atmosphere to create a magnetosphere surrounding the planet. Solar Orbiter passed by Venus just outside this magnetosphere, observing the solar wind in its calm, undisturbed state. At the same time, BepiColombo zipped through the "stagnation region," the area where the solar wind and atmosphere are expected to interact at Venus.

Together, the probes' observations provided experimental evidence that charged particles are, in fact, slowed down by this region, protecting Venus' atmosphere from erosion by the solar wind.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This is also an important finding for planets beyond our solar system, since astronomers now know there is a way for exoplanets without an internal magnetic field to retain their atmospheres like Venus has — and therefore possibly even harbor life.

Follow the author at @briles_34 on Twitter. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Briley Lewis (she/her) is a freelance science writer and Ph.D. Candidate/NSF Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles studying Astronomy & Astrophysics. Follow her on Twitter @briles_34 or visit her website www.briley-lewis.com.