Stepping into the 'Beyond': New book celebrates 60th anniversary of first man in space

Today (April 12) marks the 60th anniversary of the daring launch that sent the first human into space, paving the way for manned space exploration of the cosmos.

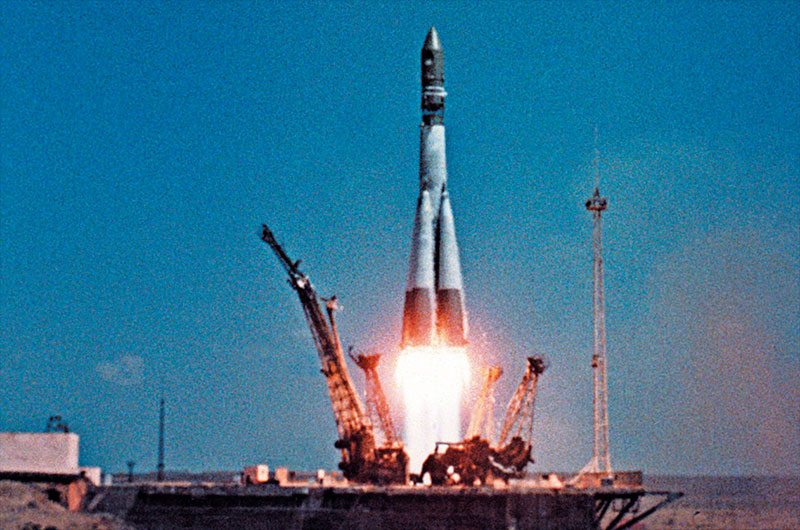

On April 12, 1961, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin became the first person to leave Earth's orbit and travel into space. His historic flight lasted 108 minutes, during which he orbited Earth in the Soviet Union's Vostok spacecraft, guided entirely by an automatic control system. This amazing feat set a significant milestone in the space race, as competition grew between the United States and the Soviet Union to develop more advanced spaceflight capabilities. With the success of Gagarin's flight, the Soviet Union had beaten the United States at putting a human in space by just about three weeks, with American astronaut Alan Shepard's suborbital flight on May 5, 1961

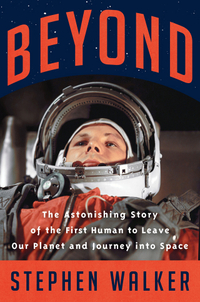

In his new book, "Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space" (Harper, 2021), author and documentary filmmaker Stephen Walker recounts intimate details of the months, and years, leading up to Gagarin's historic flight, revealing the true stories of the Soviet space program as the agency prepared to launch the first human into space. Walker also explores the many parallels between the Soviet space program and NASA as the two space agencies worked separately toward a common goal: to be the first.

Related: Yuri Gagarin, first man in space (photo gallery)

Space.com sat down with Walker to discuss his new book, the early days of the space race and the historical impact of Gagarin's flight. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. You can find the book on Amazon here, on sale starting April 12.

Buy "Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space" (Harper, 2021) by Stephen Walker on Amazon.com.

The hardcover is $25.49, a Kindle version is available for $14.99 and the audiobook is $23.49.

Space.com: Could you talk a little bit about your research on the space race between the Soviet Union and the United States?

Stephen Walker: I was asked to develop a movie [based on] some of the secret footage that we knew had been shot in the Soviet Union in the late 1950s, early 1960s, specifically about [Yuri Gagarin's] incredible flight. I knew that this stuff had all been shot secretly and so I thought, 'well, where's the footage? I've got to find this footage.' When I was commissioned to go to Russia, starting in 2012, I found some of [the footage]. Some of it is absolutely incredible — it's stuff that's never been seen before ... So our idea was going to be that we were going to press it so that it could be put on the big screen.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, it became more and more difficult to secure this material, and we don't know to this day why that actually happened — it got to the point where I thought I would have to let [the movie] go. But whilst I was doing it, I was also interviewing some incredible people. I found this wonderful couple who'd been rocket engineers in Baikonur in the late 1950s and early sixties, and they were right there — not just for Yuri Gagarin, but for Sputnik — for everything. They were husband and wife who had relocated to the middle of nowhere and they were working on this secret program that they couldn't tell their parents or anyone about. I had all these amazing interviews shot in high definition for the big screen, but we didn't have enough to make the film, so I had to let it go and it was absolutely heartbreaking.

About a year and a half, two years ago, I suddenly thought, "the anniversary is coming up — the 60th anniversary of the first human in space is a kind of big deal." It's not just a Russian thing, it's not just an American thing — it's a human thing. And when you think of it like that, it becomes terribly pivotal in all of our history. We have been on this planet for millions of years, and on April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin was the first to escape the biosphere and look at it from the outside. So I saw and met and interviewed a lot more people, and I delved into a lot more archives and read a lot more books and came back. On the first day of lockdown in London in March of last year, I started writing this book.

Related: Yuri Gagarin on Vostok 1: How the 1st human spaceflight worked (infographic)

Space.com: Many of your books have relied on extensive research, interviews and personal artifacts. What do you find most rewarding about this style of writing?

Walker: It's the confluence of ideas, places and things that are happening. Putting the two sides together so that you're in America [for one chapter] — you might be in Houston, Washington or Cape Canaveral — and then you're in Moscow or the Baikonur Cosmodrome. I was amazed when I put the timelines together: something was happening in Moscow at the same time something else was happening on the other side of the world in America. One example I wrote about was two days after Yuri Gagarin's flight, there was this massive party — the biggest party in Moscow's entire history. As that party takes place, president Kennedy is sitting in the White House, grim-faced, tapping his teeth with a pencil and saying, "what can we do?" And really, the decision to go to the moon — to start a new race — starts there in that meeting.

Space.com: That's actually a great segue to my next question, which was going to be about a quote you included from President John F. Kennedy when he says during that meeting, "If somebody can just tell me how to catch up. Let's find somebody — anybody. I don't care if it's the janitor over there if he knows how." How would you describe America's reaction to the Soviet Union's success?

Walker: I think [Kennedy] realized that, politically, he was in a bad way. Three months into the job and then suddenly this thing happens. If you actually look at the news conference that [Kennedy] gives on the day of Yuri Gagarin's flight ... he looks broken and he "extends his congratulations to Soviet Premier Khrushchev." He can't even say Gagarin's name, he just says "I extend my congratulations to the man who was involved." So now America's on the back foot, while a nation that was so comprehensively destroyed by the second World War ... put a human into space. This was a signal to the world that America had lost. So, it's existential this moment — it's literally about changing the course of history. And Kennedy knows that, which is why he had that emergency meeting. We then see Kennedy on May 25, 1961 ask for money from Congress to support this bold adventure to get to the moon within the decade, which starts the road to Apollo.

Space.com: With that said, can you talk a bit about how Gagarin's first orbital flight in 1961 ultimately jumpstarted NASA's Apollo program?

Walker: The moon landings happened because Gagarin went first into space, not Alan Shepard, who was the man designated to go first on the American side. Gagarin gets there because the Soviets see Americans hesitating, while they were taking such huge risks to get there first. Arguably, if Shepard had gone first, Kennedy would not have committed the enormous funds to the [Apollo Program].

So what prevented Alan Shepard from going first? It's what went wrong with that first flight of the chimpanzee, Ham, when the fuel ran out half a second early, as a result of which, Ham's capsule aborted and the poor chimpanzee went through this horrific flight and nearly drowned in the Atlantic ocean. Literally that half a second, I argue, changed history. If the fuel had lasted 0.5 of a second longer, Ham's [capsule] would not have aborted and Alan Shepard would have likely [flown] in March ... and beaten the Soviet Union. Then, Kennedy would not have felt the humiliation and embarrassment, and therefore the need, to commit to a massively chancy and expensive manned lunar program.

Space.com: It's interesting that you say that because it is said that by landing on the moon, the United States effectively "won" the space race. What is your opinion?

Walker: [America] won the second space race. When you say, "who was the first man in space?" A lot of people will say Neil Armstrong [the first man on the moon]. Gagarin is not well-known in the West, whereas in Russia, he is God. It is quite extraordinary how you cross a border, if you like, and you get a totally different perspective of history. So who lost what? The Soviet Union won the race to put a human in space ... and Americans won the race to put a man on the moon. One came after the other, so I think of it as a first space race, which generated the second one.

Space.com: What was your inspiration for the book and what do you hope to convey to readers about Gagarin's historic spaceflight?

Walker: What I really wanted to do was just tell a great story, most of all, which is about a pivotal moment in history. I was only a little boy when men went to the moon in 1969. I remember thinking when I was grown up I would take my kids to the moon on holiday — I really believed that. It felt terribly exciting, even as a small child. So there's obviously something that goes back to being a child of the space age. But I've always loved the idea of the freedom of being unbound from the Earth. I actually have a pilot's license and I've been flying for about 20 years ... so I do have a little sense of what it's like to kind of escape the surly bonds of Earth, even if it's only two or 3,000 feet, not in orbit.

I think it also ties back to "Shockwave," a book I wrote about Hiroshima in 2005, which was about another piece of extraordinary world-changing technology. The change we're talking about there is about destruction — it's about destroying people, buildings, life, the planet, ultimately — and "Beyond" is sort of a sequel in a funny way; it's about another piece of technology that changed history. That is, the extraordinary moment when the first human steps into the beyond ... and sees what no eyes had ever seen before. It's about the greatness that we're capable of.

Space.com: The book explores very intimate details about both the Mercury Seven astronauts and Vanguard Six cosmonauts. Can you explain some of the similarities and differences between the two groups?

Walker: The American astronauts were all experienced military test pilots. The Mercury Seven [astronauts] started their training around April 1959, at which point the Soviets had no such program, but they reacted to the American program and selected [candidates] from a much wider pool. The [cosmonauts] were younger by about 10 years, at least, and far less experienced. The reason for that is because the Americans managed to secure a level of actual control over their spacecraft, whereas the Soviet cosmonauts were actually just there to endure [spaceflight] without panicking. So you've got these two rather extraordinarily different teams.

They were also different in terms of the way they lived. The Americans became celebrities; rock stars. They were on the cover of everything, particularly "Life" magazine. They were heroes to one and all, and everybody knew their names, whereas in the Soviet Union, no one was allowed to know who the [cosmonauts] were. Their families didn't know anything about them, either. They didn't have any money or exclusive deals. Instead, they lived in tiny Soviet apartments without a telephone, refrigerator or car. Their wives had to polish floors in order to make ends meet. It was two totally different worlds. And yet, what they shared was a burning ambition to be first.

Related: Yuri Gagarin on Vostok 1: How the 1st human spaceflight worked (infographic)

Space.com: Can you talk a bit about how the Soviet Union's and America's approaches to spaceflight differed in the early '60s?

Walker: I would say that the American approach was much more cautious. I think they had to be more cautious for a very simple reason: because everything was public. They didn't let Shepherd launch in March 1961, after Ham's flight, because, and I quote somebody at the time, "if anything goes wrong, this will be the most expensive public funeral in history because everyone is going to see it." Everybody [in America] had a TV by then. But when you do things in secret, as the Soviets did, you don't have to be as cautious.

Space.com: Last year, we celebrated the 20th anniversary of continuous habitation of the International Space Station, which has been occupied by both U.S. astronauts and Russian cosmonauts. While the height of the space race in the '60s brought a lot of competition, what is your view on how the two agencies operate today?

Walker: I think there is some collaboration, definitely. But I also think the Russians are falling behind and have almost lost interest in pursuing any kind of big space endeavors. They're still putting up rockets, but if you go to Baikonur, it's falling apart. It's not like Cape Canaveral, which is pristine. And, I do see elements of a space race still. There is an economic competition, clearly, and a political competition between two parts of the world, perhaps exacerbated in recent years.

Space.com: This year marks the 60th anniversary of Gagarin's historic flight. Can you talk a bit about the fundamental impact his flight had on space exploration and how far we have come today?

Walker: He was the first to step into the beyond, which, for me, is not just a physical space, it's a philosophical space. One of the things I write about is [Gagarin's] view [from orbit] — that's kind of the "wow" for me. That view is the beginning of everything. So every single thing that we do now, in some way, goes back to that moment.

One of the things I've started to do every day [on Twitter], as interest in the book begins to build, is a post about "this day 60 years ago." The timeline starts to build in a really weird parallel with all the stuff that's happening now. It's quite nice putting those time parallels together: then and now, as we count down to that epochal moment in 1961.

Space.com: What do you hope to see in the next 60 years of human spaceflight?

Walker: I think we're going to get quite far into the solar system. I want to think that we're going to get to live on Mars ... and I think we're going to get to other places as well. But the most important thing of all is that we discover life, because that [will] change literally everything ... It means that when you look up at the stars, it's massively out there. It can't not be if it's in our own little weird remote corner of the solar system.

There was a picture I saw recently from Hubble, which was just incredible. It was a picture of a galaxy so full of stars, there was almost no black. It looks like a million brilliant points of light in space. And the idea that if we find something near to home, that will change how we look at all of that. I mean, those [stars] could be civilizations. So the future is not just about exploring, it's about meeting — it's about finding. And I don't mean finding places. I mean, connecting and meeting. And to me, that is ultimately where this goes.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.