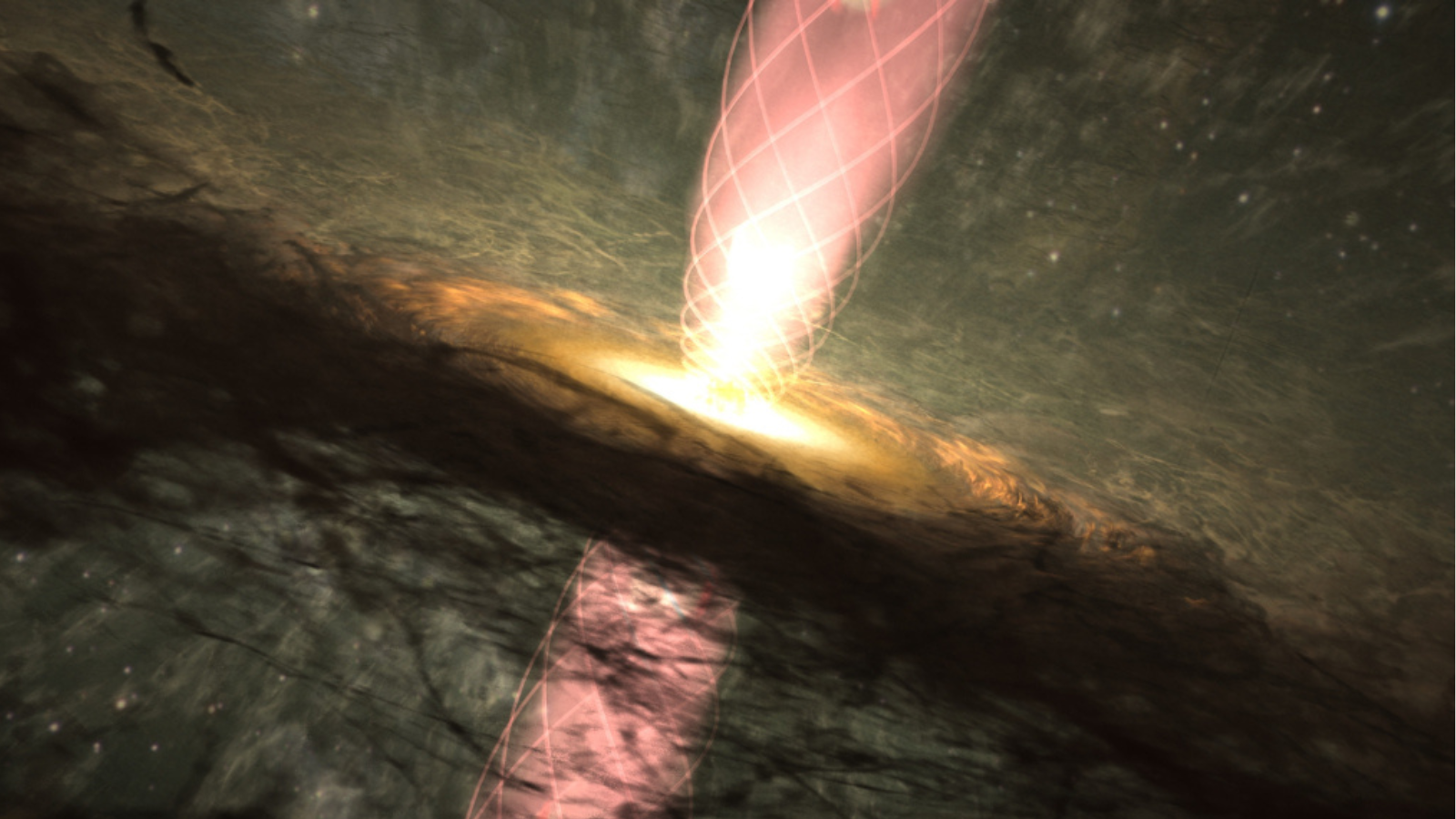

Twisted magnetic fields in space sculpt the jets of black holes and baby stars

"This is the first solid evidence that helical magnetic fields can explain astrophysical jets at different scales."

At first glimpse, it may seem like infant stars and supermassive black holes have very little in common.

Infant stars, or "protostars," haven't yet gathered enough mass to trigger the nuclear fusion of hydrogen to helium in their cores, the process which defines what a main sequence star is. Supermassive black holes, on the other hand, have masses equivalent to millions, or even billions, of suns crammed into a space no more than a few billion miles wide. For context, the solar system is estimated to be 18.6 trillion miles wide.

Yet, protostars and supermassive black holes do have at least one thing in common: They both launch high-speed astrophysical jets from their poles while gathering mass to increase in size. And new research suggests the mechanism creating these jets may be the same for these objects at opposite ends of the astrophysical spectrum.

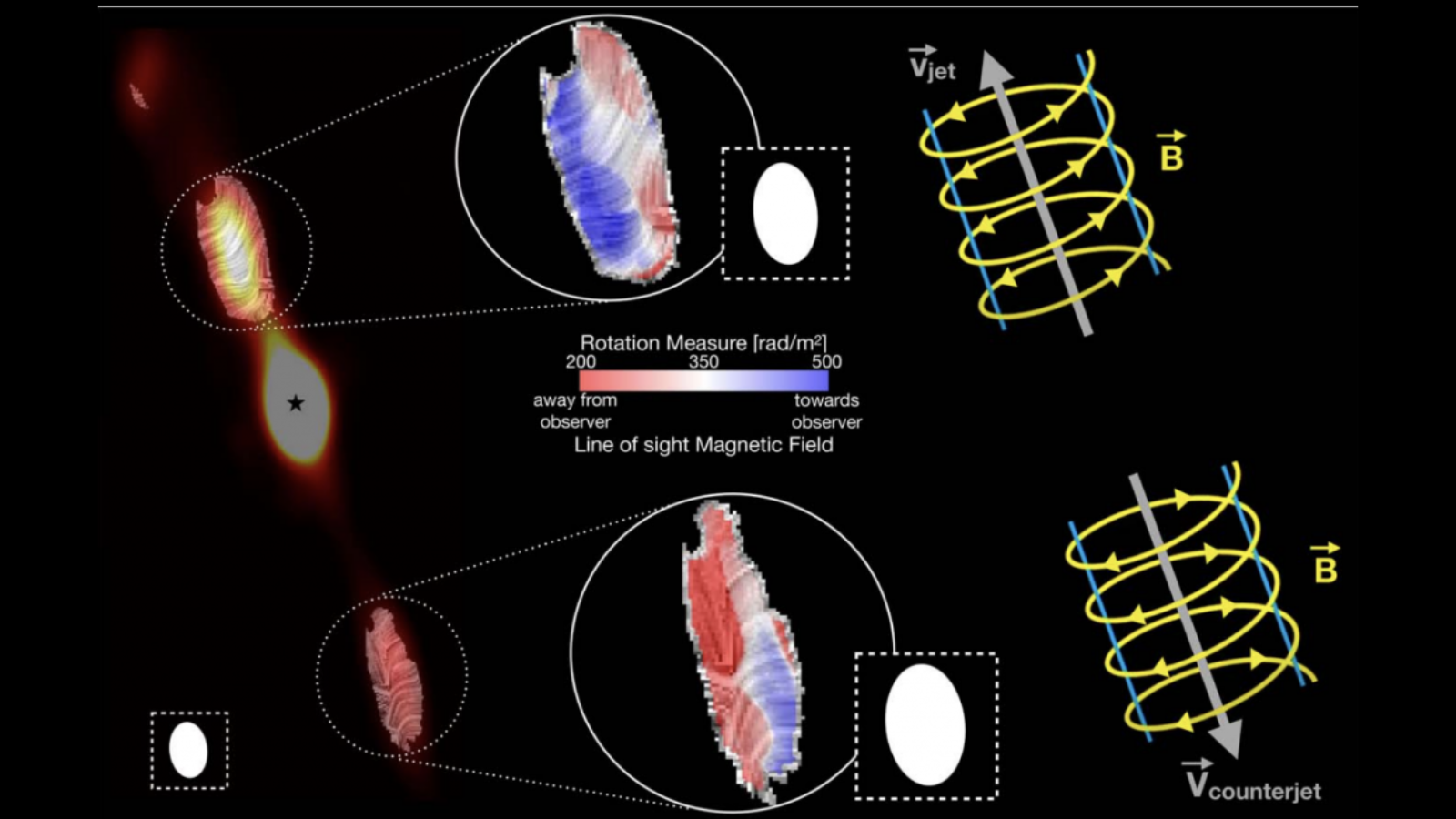

The team behind this research reached that conclusion when they detected a helix-shaped magnetic field within a protostellar jet designated HH 80-81.

HH 80-81 is the fastest protostellar jet ever seen, erupting from a star that sits at the heart of a natal cloud of gas and dust called IRAS 18162-204. This cloud is located around 5,540 light-years away. Moreover, the helical magnetic fields in the observed jets are similar to such structures seen in jets erupting from supermassive black holes.

"This is the first solid evidence that helical magnetic fields can explain astrophysical jets at different scales, supporting the universality of the collimation mechanism," Adriana Rodríguez-Kamenetzky, team leader and a researcher at the Institute of Theoretical Experimental Astronomy (IATE), said in a statement.

This isn't the first time scientists have connected the mechanisms launching jets from supermassive black holes and those emerging from protostars — however, there has never before been definitive evidence of helical magnetic fields in protostellar jets.

This evidence has been difficult to obtain because the light emitted by these jets is mostly thermal. That makes it difficult to detect magnetic field structures.

"Back in 2010, we used the Very Large Array (VLA) to detect non-thermal emission and the presence of a magnetic field, but we couldn’t study its 3D structure," Carlos Carrasco-González, team member and a researcher at the Institute of Radio Astronomy and Astrophysics (IRyA), said in the statement.

Upgrades to the VLA, a radio telescope that's about a 2-hour drive from Albuquerque, have now allowed these limitations to be overcome. As a result, the team was able to conduct a highly detailed Rotation Measure (RM) analysis of the HH 80-81 jet. The RM analysis enabled the scientists to correct for the rotation of light polarization as it passes through magnetized plasma. With this so-called "Faraday rotation" accounted for, the researcherscould discover the true orientation of the HH 80-81's magnetic field.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

“For the first time, we were able to study the 3D configuration of the magnetic field in a protostellar jet," Alice Pasetto, team member and a scientist at IRyA, said in the statement.

The first application of RM analysis to a protostellar jet revealed a definite helical magnetic field within HH 80-81. This suggests these twisted magnetic fields are indeed a universal mechanism for the launch of astrophysical jets.

The team's research was published on Jan. 7 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Aplu Dejavu all over again! I read the article "Jets From Black Holes Cause Stars to Explode, Hubble Reveals" on Gizmodo late last year, and thought, magnetic fields would have something to do with that, particularly as they would become braided or twisted along those relativistic jets and would play merry havoc with star's magnetic fields as they progressed through space.Reply

It's nice having random thoughts proved right! Of course the magnetic fields would be helical - conservation of momentum isn't abrogated just because the cause of the jet is a protostar or black hole. Unless the jet is forced into a width of an electron wide, the angular momentum's still going to be there. It's just going to be spaced out over millions of kilometres instead of neatly tied into a tight orbit.