Hubble telescope spots a black hole fostering baby stars in a dwarf galaxy

Black holes can not only rip stars apart, but they can also trigger star formation, as scientists have now seen in a nearby dwarf galaxy.

At the centers of most, if not all, large galaxies are supermassive black holes with masses that are millions to billions of times that of Earth's sun. For instance, at the heart of our Milky Way galaxy lies Sagittarius A*, which is about 4.5 million solar masses in size.

Astronomers have previously seen giant black holes shred apart stars. However, researchers have also detected supermassive black holes generating powerful outflows that can feed the dense clouds from which stars are born.

Video: Dwarf galaxy’s black hole triggers star formation

Related: The strangest black holes in the universe

Black hole-driven star formation was previously seen in large galaxies, but the evidence for such activity in dwarf galaxies was scarce. Dwarf galaxies are roughly analogous to what newborn galaxies may have looked like soon after the dawn of the universe, so investigating how supermassive black holes in dwarf galaxies can spark the birth of stars may in turn offer "a glimpse of how young galaxies in the early universe formed a portion of their stars," study lead author Zachary Schutte, an astrophysicist at Montana State University in Bozeman, told Space.com.

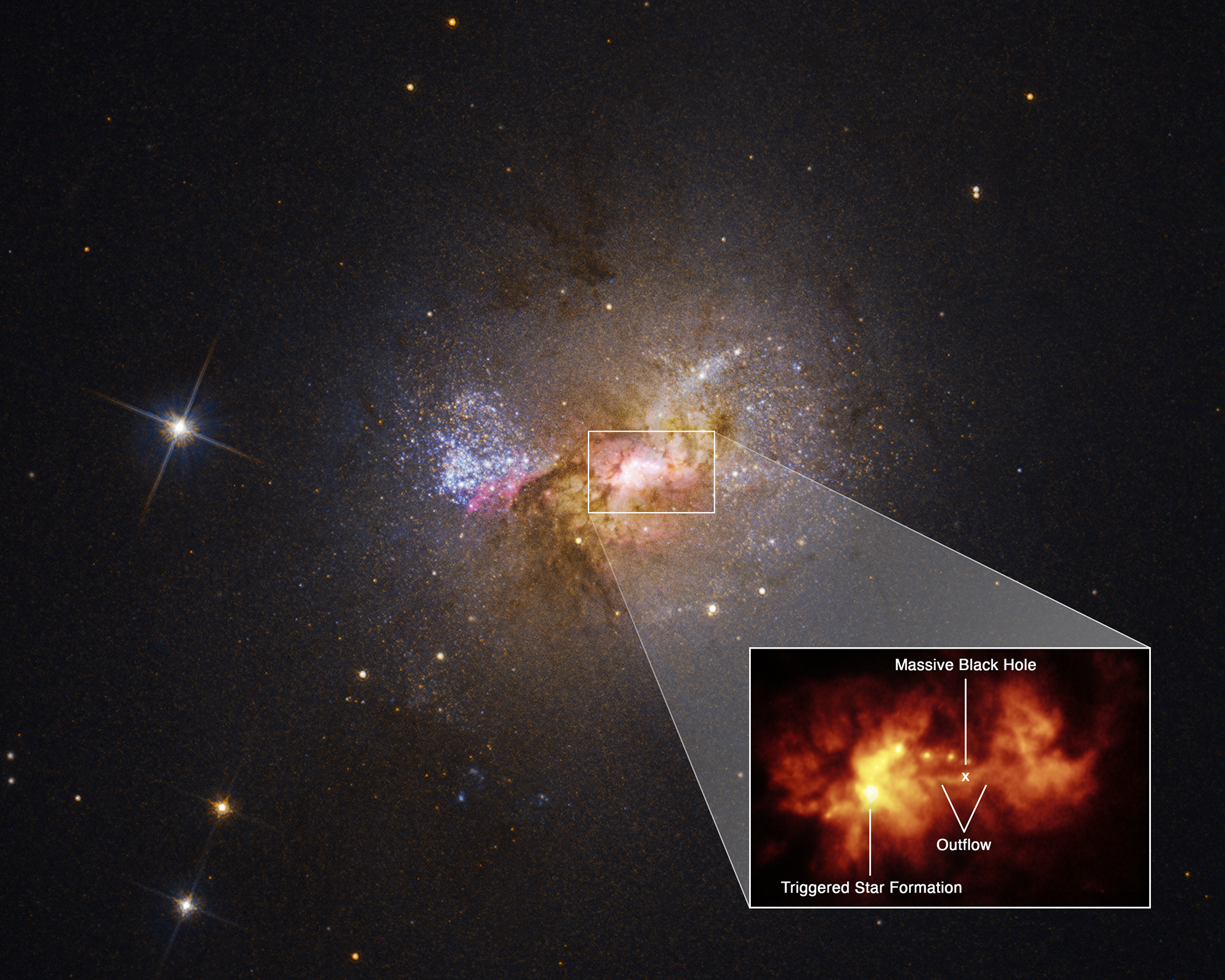

In a new study, the scientists investigated the dwarf galaxy Henize 2-10, located about 34 million light-years from Earth in the southern constellation Pyxis. Recent estimates suggest the dwarf galaxy has a mass about 10 billion times that of the sun. (In contrast, the Milky Way has a mass of about 1.5 trillion solar masses.)

A decade ago, study senior author Amy Reines at Montana State University discovered radio and X-ray emissions from Henize 2-10 that suggested the dwarf galaxy's core hosted a black hole about 3 million solar masses in size. However, other astronomers suggested this radiation may instead have come from the remnant of a star explosion known as a supernova.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the new study, the researchers focused on a tendril of gas from the heart of Henize 2-10 about 490 light-years long, in which electrically charged ionized gas is flowing as fast as 1.1 million mph (1.8 million kph). This outflow was connected like an umbilical cord to a bright stellar nursery about 230 light-years from Henize 2-10's core.

This outflow slammed into the dense gas of the stellar nursery like a garden hose spewing onto a pile of dirt, leading water to spread outward. The researchers found newborn star clusters about 4 million years old and upwards of 100,000 times the mass of the sun dotted the path of the outflow's spread, Schutte said.

With the help of high-resolution images from the Hubble Space Telescope, the scientists detected a corkscrew-like pattern in the speed of the gas in the outflow. Their computer models suggested this was likely due to the precessing, or wobbling, of a black hole. Since a supernova remnant would not cause such a pattern, this suggests that Henize 2-10's core does indeed host a black hole.

"Before our work, supermassive black hole-enhanced star formation had only been seen in much larger galaxies," Schutte said.

In the future, the researchers would like to investigate more dwarf galaxies with similar black hole-triggered star formation. However, this is difficult for many reasons — "systems like Henize 2-10 are not common; obtaining high quality observations is difficult; and so on," Schutte said. However, when the James Webb Space Telescope hopefully comes online in the near future, "we will have new tools to search for these systems," he noted.

Schutte and Reines detailed their findings in the Jan. 19 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us