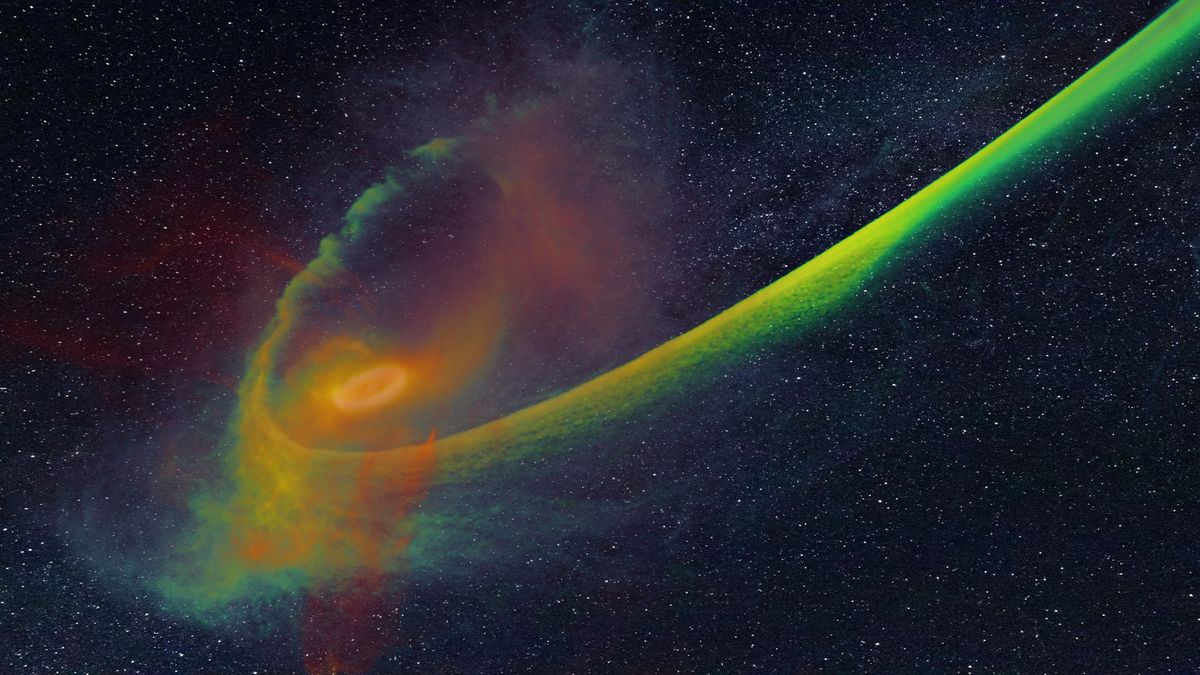

Gory simulation reconstructs violent clash as a monster black hole spaghettifies star from start to finish

A new cosmic crime scene reconstruction tells the full story of a star ripped apart by a ravenous black hole, revealing a previously unknown aspect of these tidal disruption events.

Scientists have used a sophisticated simulation to reconstruct the brutal death of a star that wandered too close to a supermassive black hole and was shredded to bits.

The team, led by researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Racah Institute of Physics, retold the entire story of this so-called tidal disruption event (TDE) for the first time and saw an unknown type of shock wave occur during the gory process. They also found that the dissipation of these shock waves powered an exceptionally intense flare during the event's brightest weeks.

In addition to explaining the brightest periods of these violent star-destroying events, the findings could help astronomers use TDEs to discover the properties of supermassive black holes, like their mass and rate of spin, and to test the limitations of Einstein's theory of general relativity.

The findings were published Jan. 17 in the journal Nature.

Related: This black hole is devouring a dying star — but it only feasts once a month

Black-hole-destroyed stars get a shock

TDEs happen when a star's orbit approaches a supermassive black hole with a mass millions or billions of times greater than the mass of the sun. As the star draws close to the supermassive black hole, the black hole's massive gravitational influence generates immense tidal forces within the star.

This is the result of the gravitational force at the closest hemisphere of the star to the black hole being much greater than that at the farther end. This tidal force causes the star to be stretched vertically while it is squeezed horizontally. This turns the star into a thin strand of stellar plasma in a process known as "spaghettification."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This spaghettified plasma falls back toward the black hole, and as this happens, it is heated by a series of shock waves. This causes the plasma to fire off a highly luminous flare that can outshine the combined light of every star in the surrounding galaxy for weeks or even months.

The simulation created by Racah Institute of Physics scientists Elad Steinberg and Nicholas Stone gets deeper into TDEs, recreating for the first time the complete picture of these events, from the star being captured by the black hole, through the initial disruption of the star, until the peak of the TDE flare.

This event reconstruction was possible thanks to pioneering radiation-hydrodynamics simulation software developed by Steinberg.

The cosmic crime scene investigation revealed a previously unknown type of shock wave occurring during the TDE, showing that these events dissipate energy at a faster rate than scientists thought. This finding told the team that the brightest periods of the TDE are powered by these shock waves and the associated energy dissipation.

According to the researchers, astronomers could continue to explore the mechanics of these powerful shock waves using real-world observations of the violent encounters between supermassive black holes and doomed stars.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

NASA spacecraft spots monster black hole bursting with X-rays 'releasing a hundred times more energy than we have seen elsewhere'

Could we use black holes to power future human civilizations? 'There is no limitation to extracting the enormous energy from a rotating black hole'

-

Helio Reply

This is interesting since the monster BHs (SMBHs) are weaker in tidal stresses at their EH. A human falling through their EH will not hardly notice it's happening. A much smaller BH has a much greater gravity gradient, hence a great place to make pasta, unless your the dough. :)

Larger scale objects like this star, however, will succumb to spaghettification since, I assume, they cover much more space, those more tidal stress.