All black holes feast chaotically, no matter how hungry they are

"This is really puzzling and exciting at the same time."

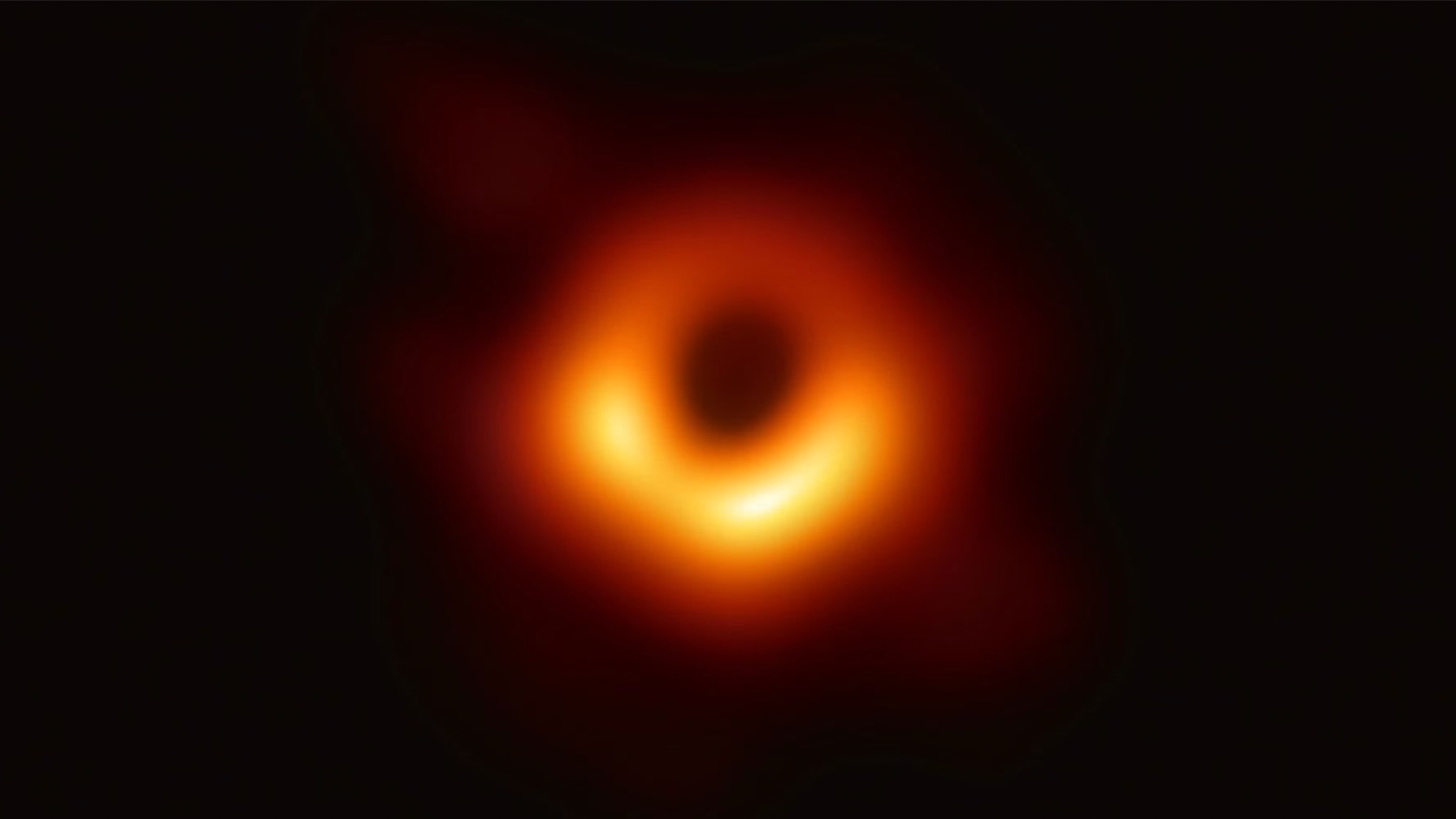

Feeding black holes lurking at the center of most galaxies gulp nearby stars, gas and dust the same way irrespective of how hungry they are, new research suggests.

Until now, there appeared to be an order to these massacres. The hungriest of black holes, which also beam out very powerful radiation, were thought to "eat" one star about the size of our sun every year. Astronomers think matter collapses into disks around these very hungry cosmic beasts, which are then fed in a somewhat organized way. By contrast, less hungry black holes were thought to take something like 10 million years to consume a sun-sized star and are thought to be surrounded by chaotic streams of matter rather than neat disks.

However, astronomers now say both systems are more similar than currently appreciated.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope spies a newborn star in its cosmic crib

The chaotic process typically associated only with the latter systems, the less bright black holes, might in fact play an important role in the way the brightest black holes feed, study lead author Ilaria Ruffa of Cardiff University told Space.com in an email.

"This result was totally unexpected and can thus completely change our understanding of the physical processes through which different types of active black holes 'eat' the surrounding material," she said. "This is really puzzling and exciting at the same time."

To arrive at their conclusions, Ruffa and her colleagues studied 136 black holes, millions of times more massive than our sun, that sit billions of light-years away from us. This included voids sitting in about 30 nearby galaxies studied by the powerful ALMA telescopes in Chile. The team found that light detected from all feeding black holes, especially in the microwave radiation region, is actually coming from disordered streams of matter.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This is "changing our view on how these systems consume matter, and grow to be the cosmic monsters we see today," Ruffa said in a statement.

It also appears, the team says, that the matter tightly bound around the black holes shone the same way in both microwave and X-ray wavelengths, hinting that for highly luminous black holes, the observed glow is "incompatible with an ordered flow of matter," said Ruffa.

Studying this light may also offer a new indirect method to estimate black hole masses, a crucial parameter to understand how these beasts, colossal in their own right but "tiny" when compared to an entire galaxy, "manage to affect — sometimes, in a dramatic way — the life of the host galaxy itself," said Ruffa.

This research is described in a paper published Dec. 5 (Monday) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

NASA spacecraft spots monster black hole bursting with X-rays 'releasing a hundred times more energy than we have seen elsewhere'

Could we use black holes to power future human civilizations? 'There is no limitation to extracting the enormous energy from a rotating black hole'