Scientists want to make moon roads by blasting lunar soil with sunlight

"Tiles could be created on the moon in a relatively short time with simple equipment."

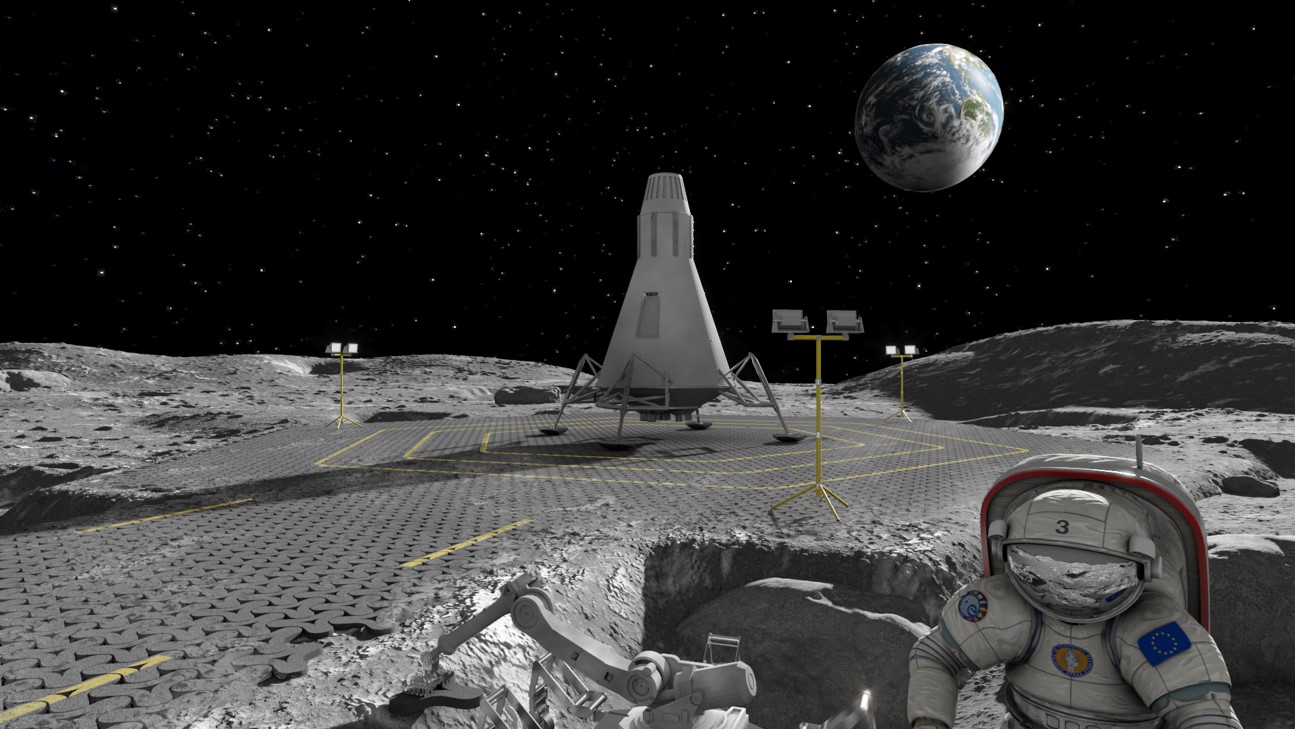

Lunar dust could one day be fused into paved roads and landing pads on the moon using concentrated sunlight from huge lenses, scientists believe, thanks to experiments on Earth that used lasers to blast simulated lunar soil.

Dust on the moon is largely made of lunar volcanic rock that cosmic impacts and radiation have blasted to a powder over millions of years. And though the moon typically appears white to us because of reflected sunlight, lunar soil is actually mostly dark gray.

Whereas Earth has wind and water to erode its soil, the moon does not — so, in moon dust, "many particles have sharp edges," Juan-Carlos Ginés-Palomares, an aerospace engineer at Aalen University in Germany, told Space.com. Thus, moon dust can prove a major hazard to space exploration.

In addition, lunar dust is generally electrically charged, "which makes it especially sticky," Ginés-Palomares said. This sticky, abrasive nature of the powder means "it can cause damage to lunar landers, spacesuits, and human lungs if inhaled."

One way to prevent moon dust from damaging rovers as they roam across the lunar surface is to have them drive on paved roads on the moon. However, lugging building materials from Earth is costly, so researchers want to rely as much as possible on lunar resources themselves And in a new study, Ginés-Palomares and his colleagues experimented with a fine-grained material called EAC-1A, which the European Space Agency developed as a substitute for lunar soil. They wanted to see if focused sunlight could melt lunar dust into slabs of rock.

Related: NASA wants a 'lunar freezer' for its Artemis moon missions

To simulate concentrated sunlight, the scientists experimented with laser beams of different strengths and sizes. These ranged up to 12 kilowatts in power and about 4 inches (10 centimeters) wide. The researchers found they could produce triangular, hollow-centered tiles about 9.8 inches (25 cm) wide and up to about 1 inch (2.5 millimeters) thick. These could interlock to create solid surfaces across large areas of lunar soil for use in roads and landing pads, they said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Previous research suggested that intense sunlight or laser beams could fuse lunar soil into dense, rigid structures. However, prior experiments never produced blocks this big, nor used light beams this large or powerful, Ginés-Palomares said.

In order to focus sunlight to generate a beam on the moon as strong as the most powerful ones used in these experiments, the researchers calculated a lens about 5.7 feet (1.74 meters) in diameter was needed.

"In this way, tiles could be created on the moon in a relatively short time with simple equipment," Ginés-Palomares said.

Future experiments should analyze how well such tiles survive rocket thrust in order to see if they could find use in landing pads, Ginés-Palomares said. Researchers can also test such techniques in simulated lunar conditions — for instance, in the absence of air and with the reduced gravity found aboard parabolic flights, he noted. "Working under these conditions is essential to demonstrate the feasibility of the technology before it can be applied on the moon," Ginés-Palomares said.

The scientists detailed their findings on Oct. 12 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us

-

Unclear Engineer This seems like a good idea.Reply

But I am not thinking it will have much value in controlling the dust. Although there is no wind, the dust still apparently moves around some, probably due to its electric charge helping suspend it and the effects of the light terminator sweeping across the surface every 2 weeks. And, since it sticks to a lot of our artificial infrastructure, it will probably be "tracked" onto these paved surfaces by vehicles and feet that move on and off the paved areas, anyway.

What we probably need to develop is some sort of electrostatic dust repulsion system. That would not only help on the Moon, but also with robotic devices sent to other places like Mars and maybe even asteroids, where dust needs to be removed from solar cells to keep the devices working. -

Unclear Engineer Yes, they should put some of their test samples on the ISS to see how they handle thermal cycling in real space before they transport a huge glass lens or dish to the Moon to make them there.Reply

One large, solid sheet of fused material is very likely to crack. But cracking still might leave a useful surface. I doubt it would just turn to dust.

Creating a tiled surface with joints would probably help. Creating layers of tiles might help a lot.