Blue Moon: Here's How Blue Origin's New Lunar Lander Works

Blue Origin is shooting for the moon. Here's how.

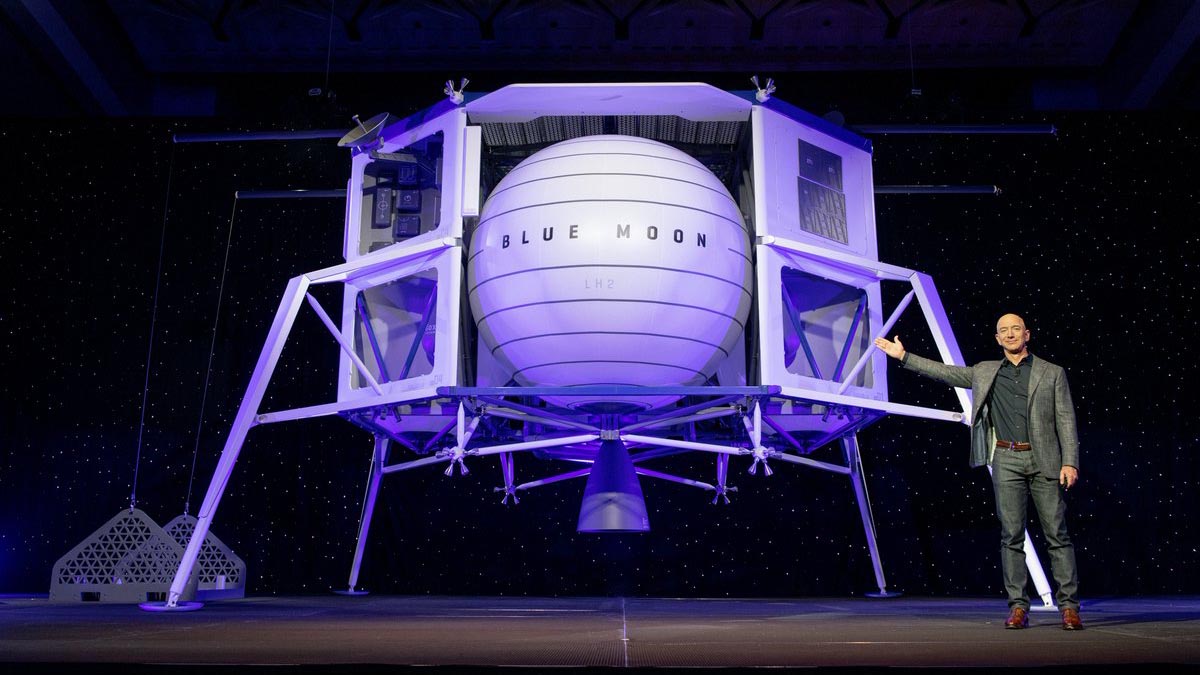

WASHINGTON — Yesterday, Blue Origin's billionaire founder, Jeff Bezos, revealed the company's plans to land a spacecraft named "Blue Moon" on the lunar surface.

During an exclusive presentation here at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center yesterday (May 9), Bezos laid out the details of Blue Moon and all the ways it can be used to explore Earth's natural satellite.

From new tech to possible crewed missions to the lunar surface, there's a lot to unpack from Bezos' presentation. We'll explain what Blue Origin plans to do with Blue Moon, as well as detail the spacecraft's design and some of its bells and whistles.

Related: Blue Origin's Lunar Lander: A Photo Tour

Blue Moon is a relatively large lunar lander that's designed to deliver science payloads, moon rovers and even astronauts to the lunar surface. It can also deploy small satellites into lunar orbit as a "bonus mission" on the way, Bezos said.

Blue Moon bears some resemblance to NASA's old Apollo lunar modules, but there are some noticeable differences. The most obvious, aside from its sleeker design, is the enormous, spherical fuel tank with the words "Blue Moon" printed in big, blue letters on its side.

It also has much smaller landing pads, or "feet," on the bottom of its landing legs. That's because the Apollo landers' engineers were worried that the lunar soil would be so soft that the lander would sink too far, but the ground was more solid than they thought, Bezos said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Whereas the Apollo landers were designed specifically for human missions to the lunar surface — and, therefore, required human hands to deploy science payloads — Blue Moon is a fully autonomous, robotic spacecraft with built-in mechanisms for dropping off science gear, including lunar rovers. Using a crane-like contraption known as a davit system, the lander will gently lower payloads from its main deck to the lunar surface. The davit system can be customized for different types of payloads, and it can drop up to four large rovers onto the moon simultaneously.

Other bells and whistles include a star tracker system and a flash lidar device that will allow the spacecraft to navigate autonomously by looking at stars in space and features on the lunar surface. "There's no GPS on the moon," Bezos said.

"Now that we have mapped the entire moon in great detail, we can use those preexisting maps to tell the system what it should be looking for in terms of craters and other features, and it navigates relative to that. It uses the actual terrain of the moon as guideposts." With that navigation system, Blue Moon will be able to touch down within 75 feet (23 meters) of its target landing site, Bezos said.

Hydrogen power

The lander will utilize Blue Origin's new BE-7 engines, which the company will begin testing this summer, Bezos said. Those new engines will be powered by a combination of liquid hydrogen (LH2) and liquid oxygen (LOX), which is "not how Apollo did it," Bezos said. Although Apollo's command modules — which stayed in orbit while the lunar modules went to the surface — did use LH2/LOX for fuel, the landers used hypergolic propellant and ran on battery power.

"We know a lot now about the moon that we didn't know back in the Apollo days or even really just 20 years ago," Bezos said. "One of the most important things we know about the moon today is that there's water there. It's in the form of ice. It's in the permanently shadowed craters on the poles of the moon, and water is an incredibly valuable resource. You can use electrolysis to break down water into hydrogen and oxygen, and you have propellants."

So, the LH2/LOX-powered engines not only provide better performance but also run on natural resources found on the moon — that is, if scientists find a way to mine the hydrogen from the moon's water ice. But Bezos seemed confident in the feasibility of that plan. "Ultimately, we're going to be able to get hydrogen from that water on the moon and be able to refuel these vehicles on the surface of the moon," he said.

The spacecraft

Blue Moon has a 23-foot (7 meters) payload bay that will stand about 14 feet (4 m) with its four landing legs fully deployed. When it's fully loaded with fuel, the lander weighs about 16.5 tons (15 metric tons). By the time it reaches the lunar surface, having burned up almost all of its fuel, the lander will weigh only about 3.3 tons (3 metric tons).

For comparison, the Apollo lunar modules that carried astronauts to the moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s were 23 feet tall and weighed 4.7 tons (4.3 metric tons) without propellant. Lockheed Martin's proposed lunar lander is a bit bigger and heavier. That lander, which would also use LH2 and LOX for propellant and has yet to receive a name, would be about 46 feet (14 m) tall. Even with an empty fuel tank, the lander would weigh 24 tons (22 metric tons) — more than seven times the dry weight of Blue Moon. When the Lockheed Martin lander's fuel tank is filled, the module will weigh a whopping 68 tons (62 metric tons).

Blue Moon may look smaller than Lockheed's lander, but it will have a bigger payload capacity. It will be able to deliver about 4 tons' (3.6 metric tons) worth of payloads to the lunar surface, compared with 1.1 tons (1 metric ton) for Lockheed's lander. A "stretched tank" variant of Blue Moon will be able to carry up to 7.2 tons (6.5 metric tons), including an added ascent stage — and some additional fuel — that would allow astronauts to visit the surface of the moon.

A lander for astronauts?

Although the Blue Moon lunar lander is designed to make one-way trips to the moon, the stretched variant with its ascent stage would enable round trips for astronauts. Once astronauts left the surface, they could, hypothetically, return to NASA's Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, a proposed lunar space station that would orbit the moon, although Bezos did not elaborate on where the Blue Moon crewmembers might go once they left the moon.

NASA aims to have some form of its lunar gateway in orbit within the next five years, because the agency won't be able to fulfill the Trump administration's ambitious request to land astronauts on the moon in 2024 without that critical piece of infrastructure.

"Vice President Pence just recently said it's the stated policy of this administration and the United States of America to return American astronauts to the moon within the next five years," Bezos said. "I love this. It's the right thing to do. We can help meet that timeline."

Blue Origin has not yet officially offered NASA its lunar lander concept as a contender for the agency's 2024 mission, but NASA plans to start soliciting proposals from private companies by the end of this month.

But Blue Origin doesn't need a NASA contract to launch Blue Moon. The company has already secured paying customers, many of whom were present at the grand unveiling, Bezos said. "People are very excited about this capability to soft-land their cargo, their rovers, their science experiments onto the surface of the moon in a precise way. There is no capability to do that today."

- Lunar Base and Gateway Part of Sustainable Long-Term Human Exploration Plan

- Lockheed Martin Proposes 'Early Gateway' to Put Astronauts on the Moon by 2024

- Elon Musk Jabs Jeff Bezos Over Blue Origin's Moon Lander

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.