Here's what to expect during Boeing Starliner's 1st astronaut test flight on May 6

2 NASA astronauts and test pilots will help evaluate Starliner's performance.

HOUSTON — A busy week is ahead of the first Starliner astronauts after their scheduled launch on May 6.

Astronauts Barry "Butch" Wilmore and pilot Suni Williams will be the first NASA crew to fly to space aboard Boeing Starliner. Their mission, known as Crew Flight Test, will run for about a week at the International Space Station (ISS) to certify Starliner for future missions to last six months or so.

Boeing and SpaceX received contracts from NASA in 2014 for commercial crew missions to the ISS. Boeing's contract for the Starliner is valued at $4.2 billion, compared to SpaceX's $2.6 billion. Despite the lower contract amount, SpaceX beat Boeing to the space station and has been running operational ISS missions since 2020. Starliner ran two uncrewed test flights in 2019 and 2022, but astronaut flights were delayed due to several technical problems that officials say are all resolved now.

There are several key milestones to look for after the Starliner astronauts launch to space at Cape Canaveral, near NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC) near Orlando, Florida. The teams shared those milestones with reporters during a media tour here, at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, on March 22. Here are some of the big events of the mission that the astronauts and their support teams on the ground will be getting ready for.

Related: 1st Boeing Starliner astronauts are ready to launch to the ISS for NASA (exclusive)

Launch

The final hours before launch of the United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket will be busy, NASA Starliner flight director Mike Lammers told reporters during a briefing at JSC. The crew will suit up in their quarantine facility at KSC and do the traditional crew walkout outside the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building. They will arrive at the pad 2 hours and 15 minutes before launch and go inside Starliner.

The spacecraft will be transferred to internal power at 80 minutes before launch, and ground teams will then do a leak check on the spacecraft 50 minutes before launch. Next, the crew access arms will be retracted 11 minutes before launch.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The last four minutes will be particularly busy, with numerous callouts, but a notable one is when the launch abort system will be armed about 75 seconds before launch.

"It's already been a busy day, but then we have liftoff. That's where my real work starts," Lammers said, noting this will be the first crewed ascent flown out of Mission Control at JSC since the final space shuttle mission, STS-135, in 2011. (SpaceX has its own mission control operations in Hawthorne, California.)

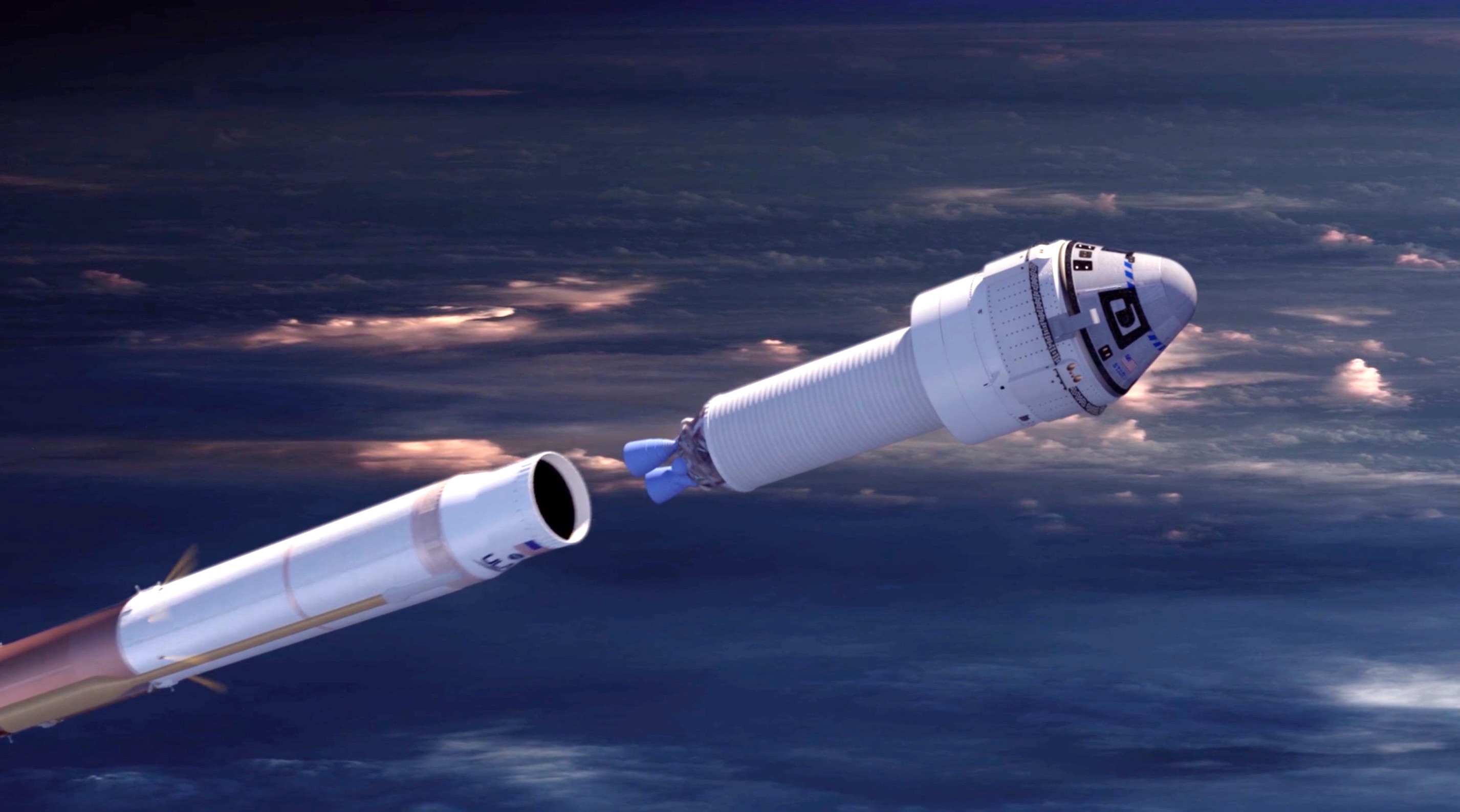

Atlas V is equipped with two solid rocket boosters or SRBs. Shortly after leaving the pad, the rocket will begin maneuvering to adjust its trajectory towards orbit. The SRBs will burn for about 90 seconds, and once spent, their empty casings will keep riding with the core stage until 2.5 minutes after launch. They will be then released and Atlas V will continue its first-stage burn until four minutes after launch.

"There's about a 15-second pause as the first stage separates [a] cover that covers a docking system," Lammers explained. Atlas V will also discard a special "aeroskirt," a 70-inch-long (178 centimeters) structure integrated into the Launch Vehicle Adapter that links Starliner up with the Atlas V's Centaur upper stage.

Then the second stage will light, with two RL-10 engines on that Centaur stage bringing the crew into space. The second stage will shut off 12 minutes after launch, and the spacecraft will separate 15 minutes after launch.

"We're suborbital still here," Lammers continued, "so we've got to do another burn." The burns for orbit will happen twice, at 31 minutes and at 1 hour and 15 minutes into the mission. Next will come the approach and docking to ISS.

If necessary, several abort sites will be on standby underneath the launch path: The pad area around Florida; an ocean zone east of Cape Cod in the Atlantic Ocean; a second ocean zone further east near St. John's, Newfoundland; and the ocean west of Shannon, Ireland.

ISS cruise

Once the launch is finished, NASA flight director Ed Van Cise joked at the same press conference, one would think it would be "a great, relaxing ride to the space station."

While operational missions aim to be that way, that cannot the case for the first Starliner as the astronauts will be doing tests for both nominal scenarios, and off-nominal scenarios.

"We're be doing things like purposely pointing it in an orientation that's say, not exactly the normal orientation for the mission, and then having the crew manually fly the spacecraft back into the direction it should be pointing," he said. "We also want to make sure that if for some reason the vehicle doesn't know where the communication satellites are located, that crew can manually fly the spacecraft to point the antennas at the satellite."

The astronauts will also "trick" the spacecraft "into thinking that it doesn't know where it is in space," Van Cise said, after which the crew will manually fly the spacecraft using a star tracker. The stars would be used to rebuild the navigation system of Starliner if anything were to go awry.

On top of these tests will be checkouts of avionics and thrusters, and having the crew do far more manual flying than required during a normal mission. The orientation of the spacecraft will also be changed to point Starliner's solar arrays towards the sun, to practice the procedure for recharging batteries if ever needed.

Following a crew sleep period, Wilmore and Williams will be roughly 1,240 miles (2,000 km) from the ISS and will then make a rendezvous and docking.

ISS docking

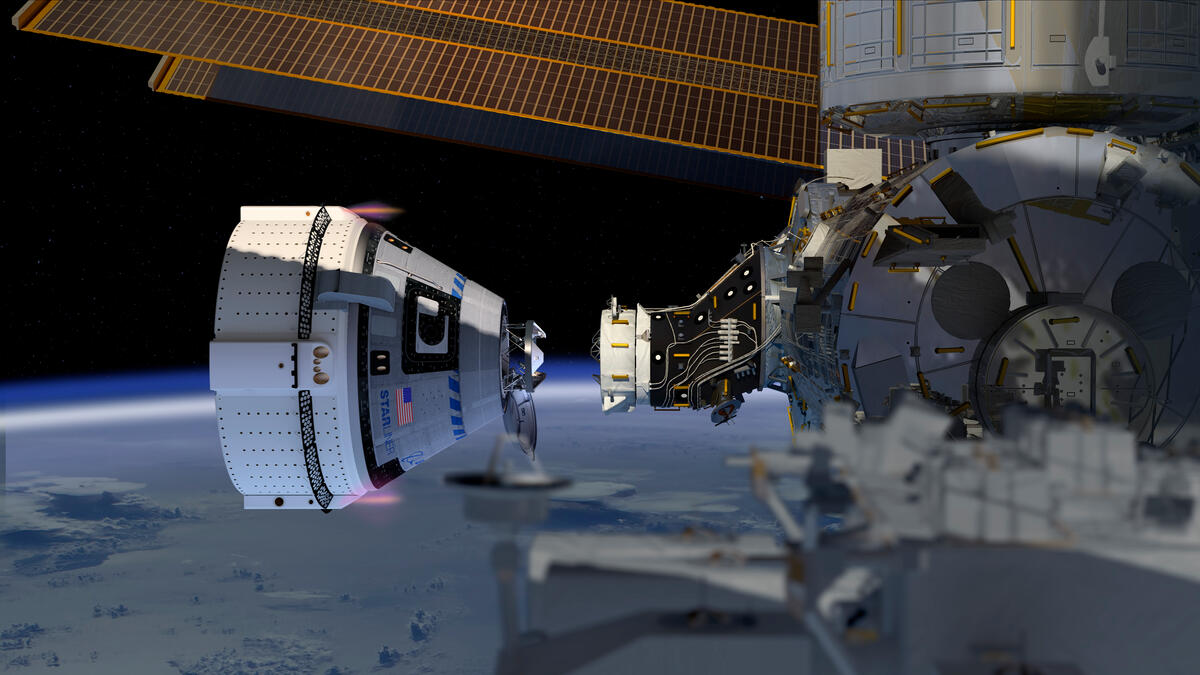

Starliner must approach the ISS within a seven-degree angle of safety. The spacecraft is designed to dock autonomously, but Williams and Wilmore are also trained to take over manually should that be needed.

"During approach, rendezvous, and docking with the station, the Starliner team will assess spacecraft thruster performance for manual abort scenarios, conduct communication checkouts, test manual and automated navigation, and evaluate life support systems. Crew aboard the station will monitor the spacecraft's approach and the Starliner crew would command any necessary aborts," NASA officials wrote of the procedure.

"Starliner will autonomously dock to the forward-facing port of the Harmony module," the agency added. "The test objective is to perform hatch opening and closing operations, configure the spacecraft for its time docked to the station, and transfer emergency equipment into the station."

ISS mission

"Our main goals of the docking mission are ... practice and validate the plan operations for long-duration missions," NASA flight director Vincent LaCourt said at the same press conference at JSC. The crew will also practice for contingencies and perform cargo operations.

The first hours after docking will include opening the hatches, going on to the space station and performing a welcome ceremony that will run on NASA Television. The ISS crew will then give the Starliner astronauts a safety briefing, and the approximately one-week mission will begin.

On the second day of docking, all the cargo will be unloaded and Starliner will be put into a "quiescent" mode, meaning extra computers will be powered off while essential equipment like lights, displays and ventilation will run as needed.

Read more: How to watch Boeing's 1st Starliner astronaut launch webcasts live online

Day 3 of docking will be a "safe haven" practice. The Starliner crew will practice an emergency run to their spacecraft, including a power-up, in case of future ISS situations that may need them (like a meteorite strike or fire.) Since operational crews would have four astronauts and not two, Wilmore and Williams will "borrow" two ISS crew members to join them.

"We'll go into Starliner, they'll close the hatch [and] basically completely power up the vehicle on their own to practice if they're getting ready for an emergency undock and return," LaCourt said.

On Day 4 of docking, the crew will do a complete power-up of Starliner and make sure the equipment is working. From there, the mission plan may change depending on how long Starliner remains docked at the station.

While the crew could leave as early as Day 8 of docking, extra days on the mission would allow them to pick up ISS tasks to help the main crew — and take some extra time off to rest ahead of landing. Before undocking, the crew will do a farewell event on television, don their spacesuits and close the hatch for departure.

Undocking, re-entry and landing

Undocking will be timed for 6.5 hours after landing, with the crew expected to move to the zenith of the ISS before turning on the engines for a departure burn.

Unlike a normal mission, the crew will briefly take manual control of the spacecraft during the cruise home to continue testing. "I like to call [this] stick and rudder flying; in fact, they can even deorbit and land in that mode," Lammers said. The crew will evaluate how the spacecraft performs in manual operations, and how that compares with the simulators in which they practiced procedures before the launch.

After a couple of orbits of Earth, the crew will finally execute a deorbit burn over the Pacific Ocean. Starliner's primary landing zone is White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, with two backup areas available: Willcox Playa east of Tucson, Arizona and Dugway Proving Ground west of Salt Lake City.

The prime landing time is at night due to weather constraints. The main constraints are low winds that are less than 10 knots and cool temperatures to protect the landing teams that will be wearing special safety suits to protect against potential leaks on the spacecraft, Lammers said. Infrared tracking and lighting will help with the darkness.

The crew will point their heat shield at the atmosphere for re-entry. Around 30,000 feet (9 km) high, the crew will jettison that heat shield and then deploy their parachute drogues. The three main chutes will deploy at 8,000 feet (2.5 km). Touchdown will happen in the desert, shortly after the airbags deploy.

A landing team will be on site, roughly 3 miles (5 km) away to avoid any falling pieces from the spacecraft. The astronauts will throw a switch to jettison their chutes, as the landing team makes their approach. Once the landing team arrives at the spacecraft, they will do brief safety check and then remove the crew. Both astronauts will be assessed medically in the field before being flown back to Houston for normal post-flight medical checks, debriefings and operations.

What's next

The first operational mission for Starliner, known as Starliner-1, is set for early 2025 at the earliest. The crew for that mission is NASA's Scott Tingle, NASA's Mike Fincke and the Canadian Space Agency's Joshua Kutryk and they are already deep in training. (Kutryk will also serve as capcom for the launch phase of CFT.)

Boeing is then expected to run regular Starliner missions to the ISS, alongside SpaceX. Currently the commercial crew program aims to bring one astronaut crew to the orbiting complex every six months. Russia's Soyuz spacecraft also does the same, occasionally with NASA astronauts on board for technical and policy reasons.

The ISS is currently expected to host missions until 2030, unless upcoming commercial space stations are not yet ready. Russia has committed to missions until at least 2028, but also may extend that partnership.

As for missions outside the ISS, Boeing officials have said they want to focus on NASA obligations first before considering private Starliner missions.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.