Starliner Spacecraft's Landing on Sunday a Critical Moment for Boeing and NASA

'Entry, descent and landing is not for the faint of heart.'

Update for Dec. 22: Boeing's first Starliner spacecraft has successfully landed in New Mexico. For photos and videos, read our full landing story here.

Boeing's first Starliner spacecraft will return to Earth Sunday (Dec. 22) to cap a rocky test flight that, despite some successes, left the capsule in the wrong orbit and unable to reach the International Space Station for NASA as planned.

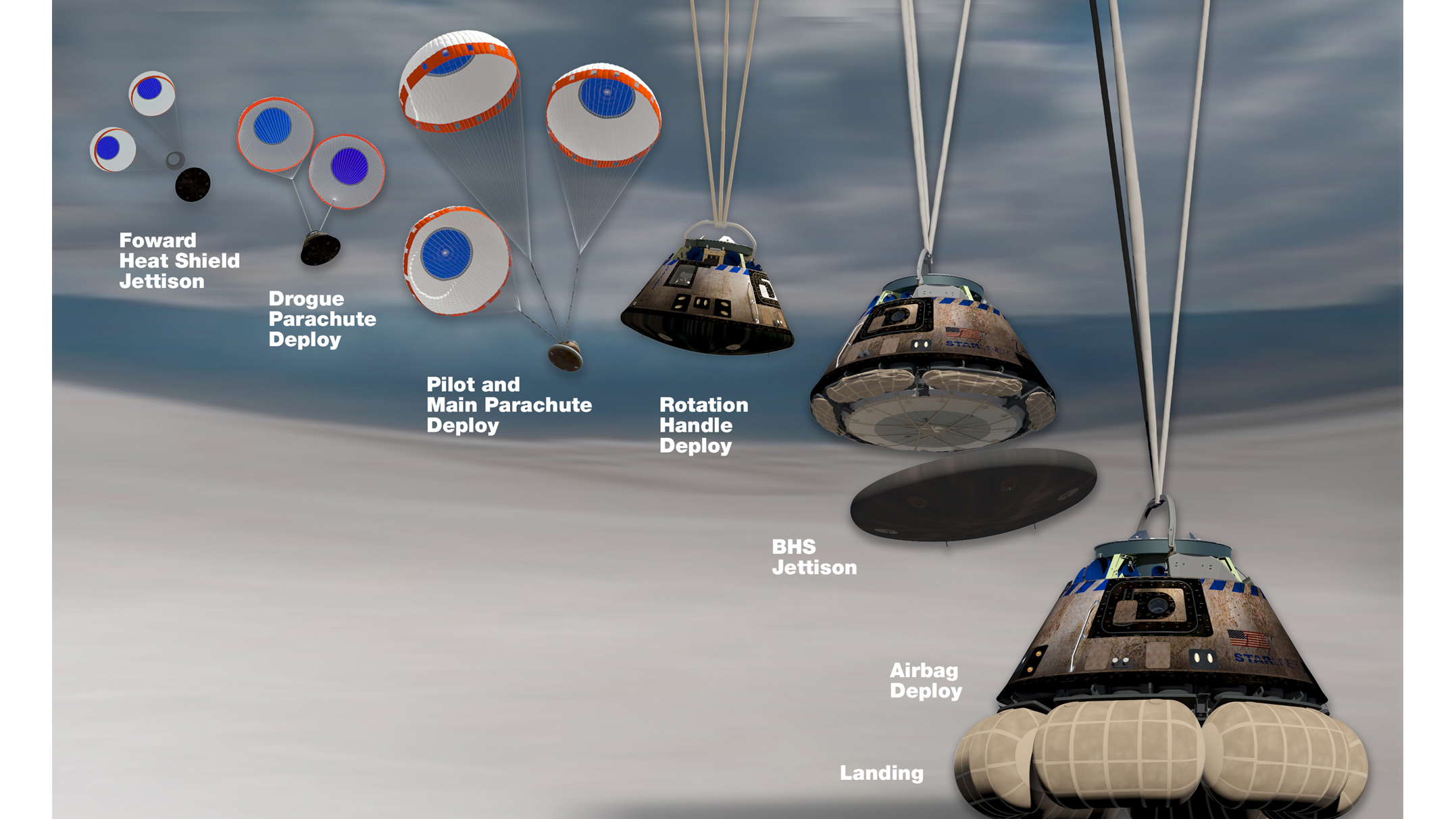

If all goes according to the revised plan, the uncrewed Starliner — which Boeing designed to eventually fly astronauts for NASA — will land at White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico at 7:57 a.m. EST (1257 GMT), six days earlier than its original Dec. 28 target. The spacecraft will rely on a heat shield to withstand the searing heat of reentry, three parachutes to slow its descent back to Earth and airbags to cushion its landing. And all of that gear needs to work perfectly for a safe touchdown.

"Tomorrow is a big day," NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said of Starliner's landing in a teleconference with reporters today (Dec. 21). "We have to be on our 'A' game."

You can watch Boeing's Starliner landing live on Space.com Sunday, courtesy of NASA TV, beginning at 6:45 a.m. EST (1145 GMT).

Video: How Boeing's Starliner Spacecraft Will Land

More: Boeing's 1st Starliner Flight Test in Photos

A critical test

"Entry, descent and landing is not for the faint of heart..."

Jim Chilton, Boeing Space & Launch Div.

A smooth, successful landing will be a redemption of sorts for Boeing's Starliner, which was left in its unplanned orbit due to a timing error with the spacecraft's mission clock. The glitch meant Starliner, which launched early Friday (Dec. 20), was unable to rendezvous with the space station to demonstrate its automated docking system, a vital capability for future astronaut missions.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But just as vital is landing safely. And that's what Boeing will attempt to show on Sunday.

"Entry, descent and landing is not for the faint of heart, and this vehicle has not entered," said Jim Chilton, senior vice president of Boeing's Space and Launch Division. "We have not gone from space to the atmosphere."

Leaving orbit

Starliner's return to Earth will occur in stages, each of which must go right for the spacecraft to land safely. First, Starliner will have to leave its current orbit, which is about 155 miles (250 kilometers) above Earth.

To do that, Starliner's service module will fire its thrusters in a so-called "deorbit burn" at 7:23 a.m. EST (1223 GMT) that will last 50 seconds. That should slow the spacecraft to about 25 times the speed of sound, Steve Stich, deputy manager of NASA's Commercial Crew Program, said in the teleconference. Mach 25 is about 19,181 mph (20,870 km/h).

After the deorbit burn, the cylindrical service module should separate from the Starliner crew capsule and perform its own maneuver to fall safely out space and into the Pacific Ocean, Stich said.

Parachute landing

The rest of the landing scenario relies on Starliner's crew capsule, which will plunge through the atmosphere on a trajectory that flies over the Pacific Ocean and crosses Baja California and Mexico, and then just west of El Paso, Texas, to reach a landing zone at White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico.

When the gumdrop-shaped Starliner slams into the Earth's atmosphere, its heat shield will heat up to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,650 degrees Celsius), according to a Boeing mission description. The spacecraft will then jettison that heat shield and prepare to deploy its parachutes.

"By the time we get to 30,000 feet [9,100 meters], we'll deploy parachutes; the vehicle will be going less than the speed of sound, less than Mach 1," Stich said.

Starliner is equipped with three main parachutes to slow its descent back to Earth. During a pad abort test in November, only two of those parachutes deployed during a Starliner landing, a glitch Boeing pegged to a misaligned pin in the parachute rigging system.

Chilton said both Boeing and NASA have checked and double-checked that the pins in the current Starliner's parachutes were installed correctly.

"We did have a NASA team go in and look at all the closeout photos," Stitch added. "The parachutes on this spacecraft were rigged correctly."

Starliner's big test

At 3,000 feet (900 m), air bags should inflate on Starliner's base. Those airbags are designed to cushion the impact of landing on astronauts inside the spacecraft.

While there are no human astronauts on this Starliner, the spacecraft is carrying "Rosie the Rocketeer," a spacesuit-clad anthropomorphic test dummy equipped with sensors to measure what astronauts will feel.

"We're going to be able to measure how the human would receive the Gs during entry, and also as the parachutes deploy and as we land," Stich said. "We can measure that environment on Rosie and then extrapolate how a human would do in that environment."

Related: Boeing's CST-100 Starliner Space Capsule (Infographic)

After landing, teams from Boeing and NASA will arrive to recover the vehicle (and its Rosie dummy) to see how Starliner and its systems performed during the trip home.

About the only thing Starliner will not have done during its test flight is the actual docking with the space station. Timing issue aside, the spacecraft fared well during launch and its major systems performed as expected in orbit, Chilton said. Engineers were also able to to deploy and retract Starliner's docking system to make sure it would work during actual dockings.

But just like launch, landing is a test that stands apart, Chilton said.

"Not all objectives are created equal,"he added. "Make no mistake. We still have something to prove here on entry tomorrow."

Visit Space.com Sunday, Dec. 22, for complete coverage of Starliner's OFT landing at White Sands Space Harbor, New Mexico.

- Boeing in Space: The Latest News, Images and Video

- How Boeing's Starliner Orbital Flight Test Works: A Step-By-Step Guide

- Starliner's Atlas V Rocket Ride Is Wearing a 'Skirt' for Launch. Here's Why.

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Instagram.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.

-

Fugldod In the article it says "Mach 25 is about 19,181 mph (20,870 km/h). " Maybe I am missing something but the mph to kph conversion looks wrong.Reply