Boomerang meteorite may be the 1st space rock to leave Earth and return

"Nobody knows what this stone is really worth."

A dark reddish-brown stone, picked up from the Sahara desert in Morocco a few years ago, appears to be an Earth rock that was flung into space where it stayed for thousands of years before returning home – surprisingly intact.

If scientists are right about this, the rock will officially be named the first meteorite to boomerang from Earth.

The discovery team's work was presented last week at an international geochemistry conference and has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

"I think there is no doubt that this is a meteorite," said Frank Brenker, a geologist at the Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany, who was not involved with the new study. "It is just a matter of debate if it is really from Earth."

Related: Over 100 space rocks collected by meteorite hunter Geoffrey Notkin are up for action today

Early diagnostic tests show the unusual stone features the same chemical composition as volcanic rocks on Earth. Interestingly, however, a few of its elements seem to have been altered into lighter forms of themselves. These lighter versions are known to occur only upon interacting with energetic cosmic rays in space, which provided one of two key pieces of evidence declaring the rock's trip beyond Earth, geologists say.

The measured concentrations of these lighter elements, called isotopes, "are too high to be explained by processes taking place on Earth," said Jérôme Gattacceca, a geophysicist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research who is leading the investigation of the unusual meteorite, which was officially named Northwest Africa 13188 (NWA 13188).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Gattacceca and his colleagues strongly suspect the rock was first hurled into space after an asteroid pummeled into Earth roughly 10,000 years ago. The only other natural event capable of catapulting rocks to high altitudes is a volcanic eruption, but geologists say that possibility is highly unlikely to explain the latest findings. Rocks blasting from even the record-breaking Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai submarine volcano last year peaked at 36 miles (58 kilometers) — well before the edge of Earth's atmosphere, a threshold the meteorite seems to have flown far beyond.

Once hurled into space past Earth's protective blanket, NWA 13188 would've been susceptible to galactic cosmic rays, made of high energy particles that arise from distant exploding stars and penetrate our solar system at light-like speeds. Such abundant beams are known to bombard meteorites and leave behind distinct, detectable isotopic imprints like beryllium-10, helium-3 and neon-21. In NWA 13188, levels of these elements are higher than those found in any rock on Earth, but lower than in other meteorites. This shows the intriguing rock might've spent some 2,000 to a few tens of thousands of years in orbit around Earth before re-entering its atmosphere, scientists say.

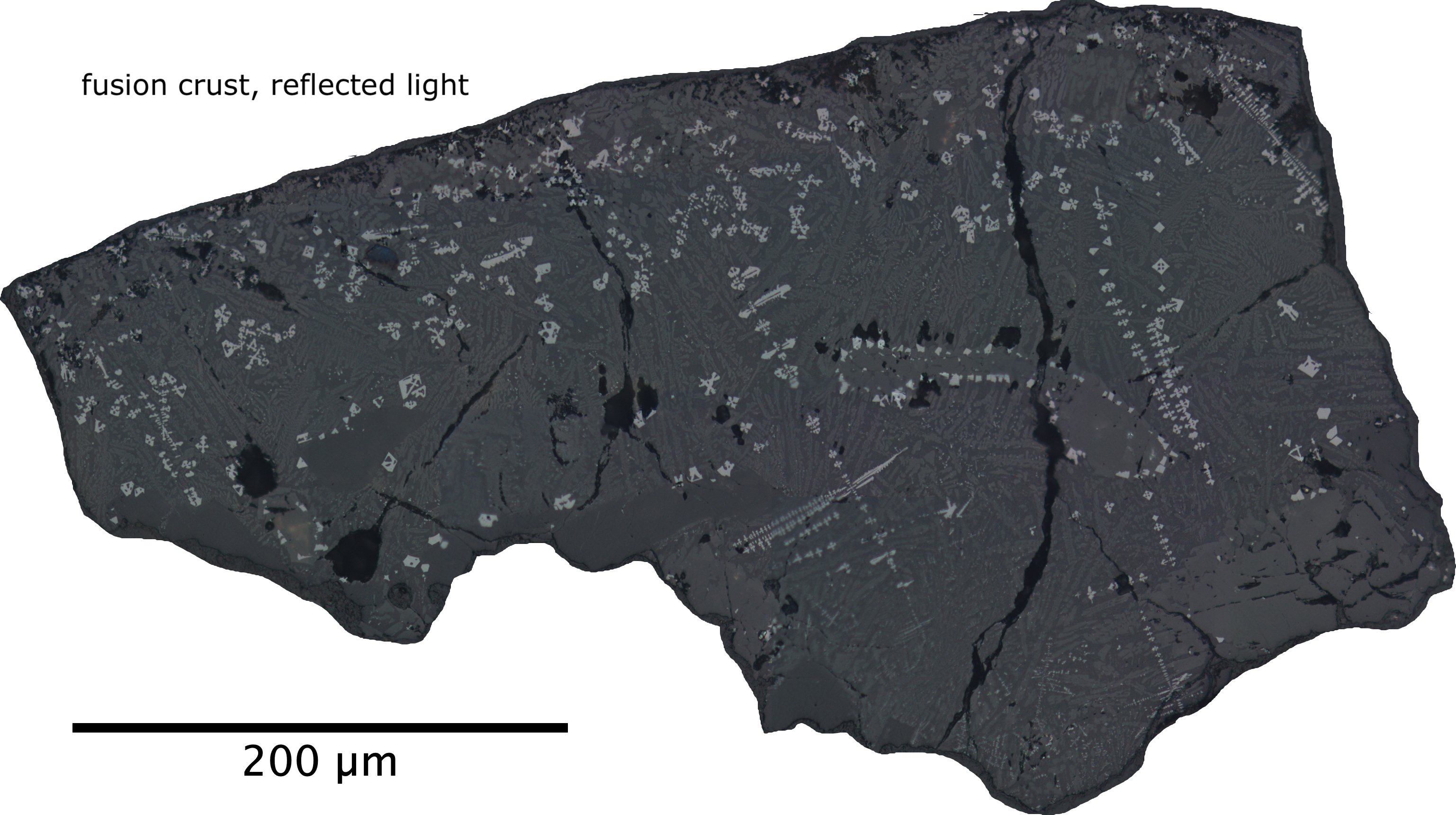

The second crucial clue divulging the rock's trip to space is its glossy coat of melted surface called a fusion crust, which forms when space rocks race through Earth's atmosphere during their journey to the ground.

The 1.4-pound NWA 13188 was purchased in 2018 at one of Europe's largest annual mineral and gem shows in Sainte Marie aux Mines, France, by Albert Jambon, a retired French professor from the Sorbonne University of Paris. He said he stays in touch with meteorite hunters and dealers and has bought nearly 300 meteorites for his university in the past two decades.

"I purchased this one just because it was odd," said Jambon. "Nobody knows what this stone is really worth."

The Moroccan dealer who sold the meteorite to Jambon very likely bought it from nomadic Bedouin tribes collecting peculiar stones in the Sahara, so it remains a mystery exactly where NWA 13188 landed after it re-entered Earth. Two years ago, Jambon teamed up with Gattacceca, a long-time collaborator who classifies meteorites for private collectors.

The team's preliminary analysis on the boomerang meteorite hasn't yet convinced other geologists, because the conclusions drawn so far are not indisputable that the rock is, in fact, from Earth.

"It is an interesting rock that would deserve more investigations to be conducted before making extraordinary claims," said Ludovic Ferrière, a curator of the rock collection at the Natural History Museum Vienna in Austria, who was not involved with the new study.

Gattacceca's team also hasn't yet determined the age of the meteorite, a necessary indicator of its origin. The rock was classified as an ungrouped achondrite, and meteorite members of this class are tagged at 4.5 billion years old — the same as the solar system. If NWA 13188 is an Earth rock, however, it must be a lot younger.

Another critical concern is the lack of a large impact crater on Earth young enough to fit the proposed timeline. Gattacceca and his colleagues estimate a crater about 12.4 miles (20 km) wide would have had to form if a 0.6-mile (1 km) wide asteroid crashed into Earth just 10,000 years ago. Among the 50 of the 200 known impact craters on Earth that are the required size, none of them are younger than millions of years.

The Sahara, where NWA 13188 was found, is home to 12 craters, only one of which is 11.1 miles (18 km) wide and at least 120 million years old, according to the Earth Impact Database, a repository of confirmed impact craters on Earth. Although there are dozens of possible impact craters in the African continent pending verification, critics say a 10,000-year-old crater is impossible to overlook.

"Such a very recent impact crater would definitely have been discovered," said Ferrière, who has found and confirmed a few impact craters including one in Congo. Asteroids transfer their momentum to the ground where they strike, amplifying local pressures and temperatures to such extremes that Earth rocks melt, and those "within such a large recent crater would still be hot," he said.

Other pending measurements include unambiguous data about how much shock from the original impact the stone absorbed. This unique signature can be detected in the permanently altered microstructures of the mineral crystals forming the rock. Estimating the meteorite's shock levels is "something that can be checked or done in one hour or so max, using naked eyes," Ferrière said, "thus, not costly and a very important observation in this case."

If the discovery pans out, NWA 13188 will inaugurate a genre of boomerang meteorites, although there is no official name for such a classification at the moment. A few geologists are calling the group "terrestrial meteorites."

The only confirmed member so far is a tiny chunk of Earth that was dug up on the moon by Apollo astronauts in 1971.

Editor's note: This article was corrected on Aug. 14, 2023 to clarify the names of the isotopes beryllium-10 and helium-3.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

-

Unclear Engineer My first thought when I read this was to wonder if this meteorite could be from the Moon, rather than from Earth. It would be much easier for an asteroid strike on the Moon to send a chunk of the Moon to Earth than vice versa. But, then I read near the end that a meteorite that is believed to be from Earth was found on the Moon by NASA astronauts.Reply

However, that seems to be a major stretch. The link in the article says about the bit of Earth found on the Moon:

". . . a 0.08-ounce (2 grams) fragment composed of quartz, feldspar and zircon, all of which are rare on the moon but common here on Earth. Chemical analyses indicated that the fragment crystallized in an oxidized environment, at temperatures consistent with those found in the near subsurface of the early Earth . . ."

"The available evidence suggests that the fragment crystallized 4.1 billion to 4 billion years ago about 12 miles (20 kilometers) beneath Earth's surface, then was launched into space by a powerful impact shortly thereafter.

"The voyaging Earth rock soon made its way to the moon, which was then about three times closer to our planet than it is today. The fragment endured further trauma on the lunar surface. It was partially melted, and probably buried, by an impact about 3.9 billion years ago, then excavated by yet another impact 26 million years ago, the researchers said."

Or, maybe we don't know that much about the Moon to begin with. If something unexpected was found in the small amount of lunar material the Apollo astronauts brought back, it is hard to claim that it is really "rare" on the Moon. And, to have it undergo a history of being disturbed by 3 impacts seems to imply that there should be a lot more of the same thing on the Moon, both scattered on its surface and buried well under the surface.

So, back to the meteorite found in the Sahara that is thought to be from Earth, could that be a piece of the Moon that is similar to the piece of moon that is thought to be from the Earth? It seems like a piece of the Moon floating to Earth over a few thousand years after a large impact on the Moon would be much more likely, considering we have no visible impact crater on Earth that fits the calculated parameters to launch this rock from Earth, while the Moon is full of undated craters. -

skynr13 Could this be a piece of the Earth that broke off when the Moon was formed over 4 billion years ago and now has returned? It could be compared to the rock from Earth found on the Moon to detect how much they are alike. It should as least be dated to determine it's age, other spectral analysis should also be performed. Why should NASA now go all the way to the Moon to determine the origin of the Moon when they can do it right now here on Earth!Reply -

Unclear Engineer The argument for the Sahara meteorite is that the amount of changes to the isotopic composition indicate only thousands of years exposure to cosmic rays, not 4 billion years of exposure. So, even if it was some part of Earth that somehow ended up on the Moon after the theorized impact between proto-Earth and "Thea" 4 billion years ago, it still would have had to be buried on the Moon until an impact there sent it out into space for several thousand years of effects from cosmic rays before it came down to Earth in the Sahara.Reply -

skynr13 I actually wasn't sure how long it had been exposed to Cosmic rays. When they say thousands, sometimes they mean thousands and thousands! It could have been inside a meteor that mostly came apart as it's core, or most of the exposed surface burned up in the atmosphere. Still, how would it have gotten into space and only been there a thousand years? You read how large they said the initial meteor crater would have to be to eject it past the Karman line!Reply -

Unclear Engineer The linked article also has a puzzle for me: It says that the bit of Earth thought to be in the Apollo moon sample crystalize in an oxidized environment about 4 billion years ago about 12 miles below the Earth's surface. That was about 1.5 billion years BEFORE the "Great Oxygenation Event" on Earth, so the "oxidized environment" on Earth 4 billion years ago was not a product of biology. So, why couldn't the Moon have some sort of oxidized environment some depth below its surface 4 billion years ago, too? And, although "quartz, feldspar and zircon, all of which are rare on the moon but common here on Earth" are not common on the Apollo samples, do we really have enough samples or other data to say that it is not present on the Moon at depth, or at other surface sites? We are only talking about a 0.08 ounce fragment in about 100 pounds of Moon surface rocks.Reply -

slicksister The boomerang meteorite article mentioned it contained Helium-10. I was surprised that Helium could contain so many neutrons (8) and looked up the isotopes of Helium on wikipedia. It indeed exists, but appears to have a half-life measured in yocto-seconds, 260 ys or 2.6*10^-22 seconds. That's so short they also supplied a resonance figure of 1.76 MeV. How ever could the authors detect this Helium-10??? Makes me question the entire article.Reply -

Unclear Engineer Well, Beryllium-3 is an impossibility, because, to be beryllium, it needs to have at least 4 protons, not to mention some neutrons.Reply

So, I think this is just a typo (or brain fart) that should have been He-3 and Be-10. -

slicksister Reply

thanks. makes more sense. (I should've caught the Be-3 goof as well!)Unclear Engineer said:Well, Beryllium-3 is an impossibility, because, to be beryllium, it needs to have at least 4 protons, not to mention some neutrons.

So, I think this is just a typo (or brain fart) that should have been He-3 and Be-10.