For the past week, I have been seeing quite a number of websites promoting an eclipse of the full moon on the night of the Fourth of July U.S. holiday.

One website even went so far as to list the lunar eclipse among the top 10 "can't miss" celestial events of 2020. And USA Today has said: "If your fireworks display is canceled on July Fourth this year because of the coronavirus, there's still something in the sky to look for over the weekend: a lunar eclipse."

Related: July full moon 2020: 'Buck Moon' lunar eclipse meets Jupiter

So, as a public service to those of you who might have been eagerly looking forward to this upcoming celestial event, take it from me: If you miss this eclipse, it won't be a big deal.

In fact, even if you're looking, you're going to miss it. It's no doubt a poor consolation prize compared to an already cancelled fireworks show.

Now you might be a bit confused at this point ... there will indeed be a lunar eclipse late on Saturday night. The only problem is, the eclipse will be taking place right before your very eyes and you won't notice a darn thing.

The reason? It is a penumbral lunar eclipse.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Defined literally, an eclipse is: "An obscuring of the light from one celestial body (in this case, the moon) by the passage of another (the Earth) between it and the observer, or between it and its source of illumination (the sun)," according to the Oxford Dictionary.

So, allow me to explain how our nearest neighbor in space can be "eclipsed" and yet in this case, not actually be hidden.

Two shadows for the price of one

Quite often, with an impending eclipse of the moon looming, we are told that the moon will be eclipsed by the shadow of the Earth. But to be strictly precise, the Earth casts not one but two shadows out into space. The most noticeable is a dark, slender, tapering cone of darkness that extends out into space for some 857,000 miles (1.38 million kilometers), called the umbra.

During a lunar eclipse, wherever the umbra falls upon the moon's surface, a hypothetical astronaut who might be located on that part of the moon would see the Earth completely cover the disk of the sun and hence he or she would be plunged into darkness. Watching from here on the Earth, we would see the umbra projected as a curved zone of darkness, dramatically cutting into the moon’s face; to the ancients it appeared as if some invisible monster was "biting" into the moon.

Surrounding the umbra is the penumbra, or partial shadow, also conical but much larger.

The penumbra is simply the half-shadow that lies outside every deep shadow, whether it's cast by the Earth or a house. Were our hypothetical astronaut positioned just outside of the edge of the umbra, he or she would be very deep into the penumbra; looking up from the lunar surface they would see the Earth covering all but a narrow sliver of the sun in the lunar sky. And looking in all directions, the illumination of the lunar landscape would appear noticeably subdued.

Related: How lunar eclipses work (infographic)

Low-key darkening

Penumbral eclipse begins: 11:07 p.m. EDT (0307 GMT).

Maximum eclipse: 12:30 a.m. EDT (0430 GMT)

Penumbral eclipse ends: 1:52 a.m. EDT (0553 GMT).

It's not complete darkness, but still, the overall lighting coming from that remaining sliver of sunshine would be considerably dimmer than normal. And from here on the Earth, looking up toward the moon while we wouldn't see a sharp curve of darkness, rather we would notice that a part of the moon looked somewhat "tarnished" or "smudged." That's usually all that is noticed during most penumbral lunar eclipses — just a very subtle shading.

But you're not even going to see this.

On Saturday night, the moon will skim partially through the southern part of the penumbra. That means the upper part of the moon will be inside the penumbral shadow. However, the geometric magnitude of this eclipse is listed as 0.3546. That means that just over one-third of the moon's diameter will be inside of the so-called "half-shadow" at the time of maximum eclipse.

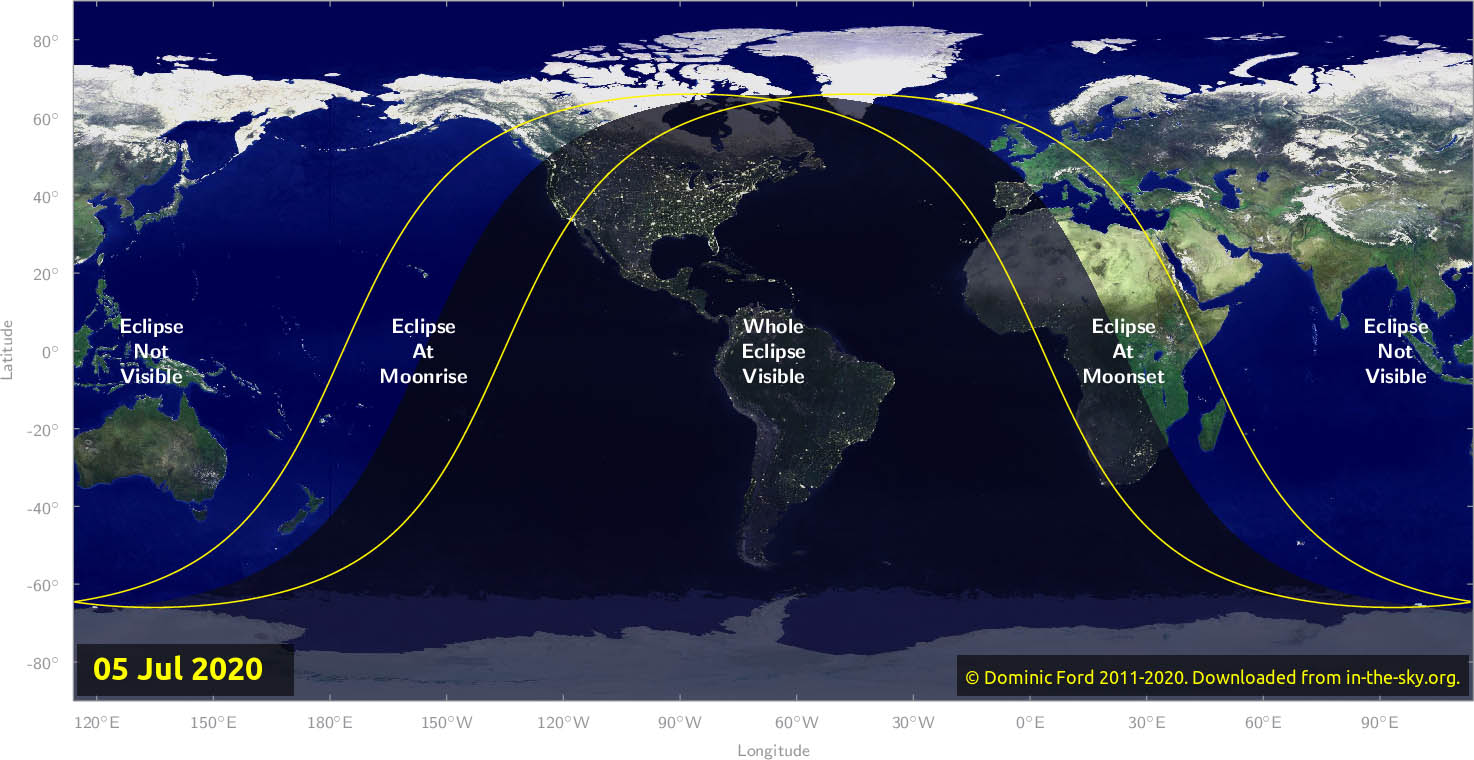

Related: Lunar eclipse 2020 guide: When, where & how to see them

No noticeable change

If you see the 2020 Buck Moon lunar eclipse, let us know! Send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com to share your views.

So, the lower two-thirds of the moon will be completely outside of the penumbral shadow. How about the upper-third? Will we be able to notice any darkening?

The answer is a most definite "no." If our hypothetical astronaut were situated on the lunar surface in the region north of Mare Frigoris (the "Sea of Cold"), they would see the Earth covering about one-third of the sun. But that would not have any noticeable effect on darkening the lunar landscape; everything would look pretty much the same as it would without any of the sun being covered.

And as seen from here on Earth at that moment — 9:30 p.m. PDT or 12:30 a.m. EDT on Sunday (0430 July 5 GMT) — if you're looking up at the moon you would very likely see ... nothing.

Yes, the calendars and almanacs are correct. The moon is officially full and at that moment will be undergoing an eclipse.

It's just that the moon’s passage on Saturday will take it through an exceedingly weak part of the penumbra and as such the moon will retain its normal guise.

A better option

In general, most people don't notice the penumbral shadow projected on the moon until at least 70% of its diameter is covered. Some people who have very acute vision and better-than-average perception might notice an ever-so-slight shading when only 50% of the moon is inside the penumbra.

But in the case of Saturday night, the obscuration amounts to just a tad over 35%; not enough to make any kind of visual impact.

If you really want to see a penumbral eclipse that will make an impact (sort of), you will not have too long to wait.

On Nov. 30, very early that Monday morning (the predawn hours) another penumbral lunar eclipse will take place. However, on this occasion the geometric magnitude will be 0.8285, or more than four-fifths of the moon's diameter will be inside of the penumbra at maximum eclipse, likely resulting in a noticeable shading of the upper portion of the moon.

To be sure, though, still a most "underwhelming" event.

Editor's note: If you capture a photo of the lunar eclipse and would like to share it with Space.com for a story or gallery, send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.